Why do economies grow?

It’s a simple recipe, actually.

Add rising labor productivity—total output per worker—to an increase in the number of people working, or some combination of the two. Shake vigorously. Voilà.

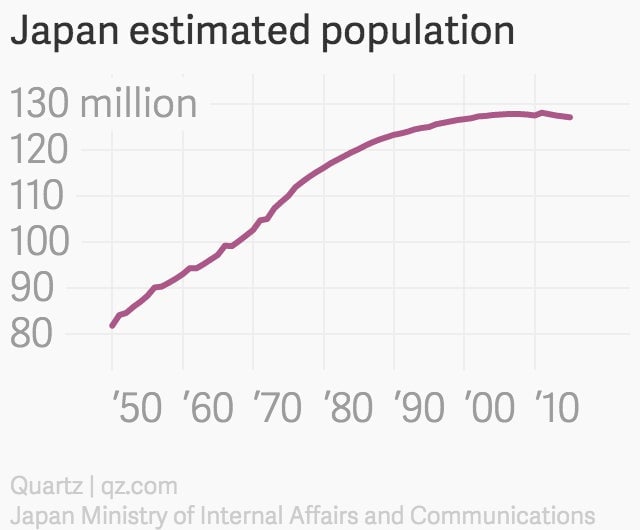

But it’s easier said than done, especially for countries like Japan where populations are stagnant or shrinking. The population of the world’s third-largest economy—roughly 127 million—has been in decline since 2010, due to low birth rates and Japan’s traditional ambivalence about immigration.

In fact, weak population growth is one of the reasons that Japan has been locked in a decades-long battle to re-energize an economy that remains deeply damaged by the real estate and banking bust it suffered in the early 1990s.

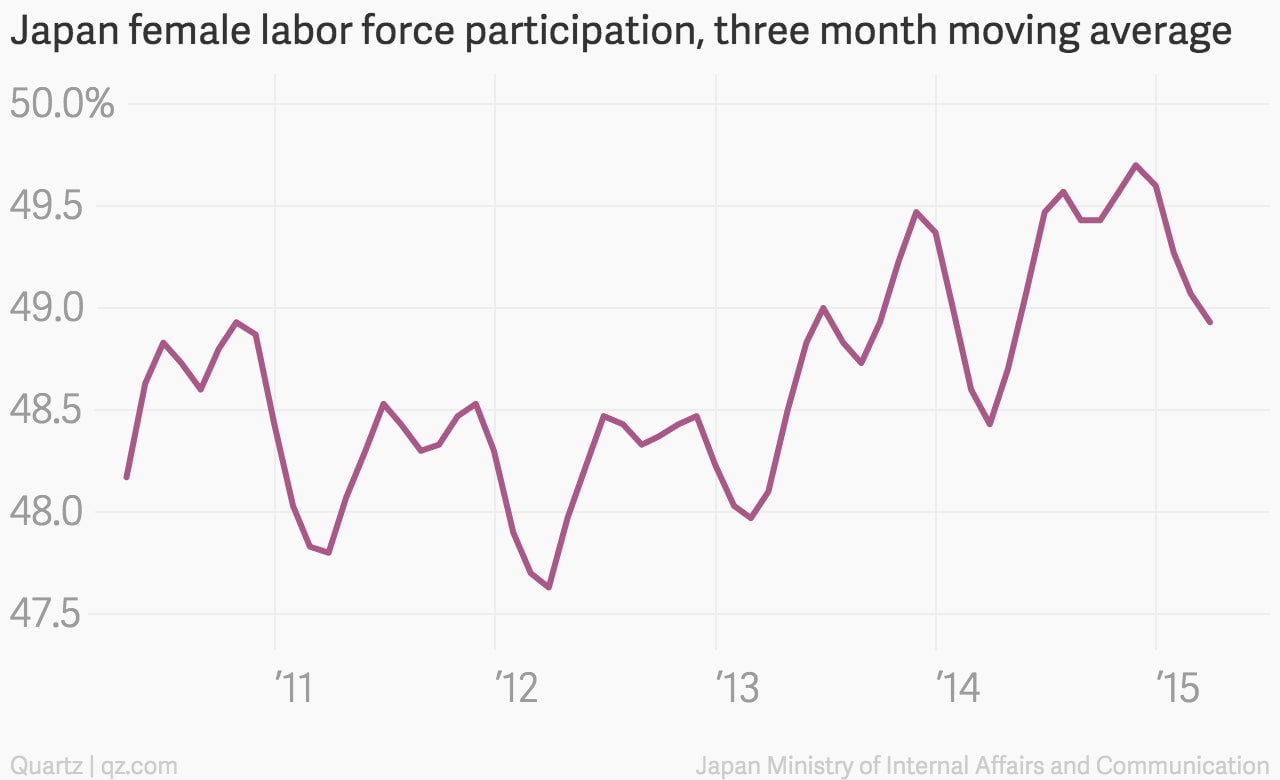

Prime minister Shinzo Abe’s three-part program of aggressive monetary policy, aggressive government spending, and labor market reform is aimed at jolting the economy back to life. And there are some signs it’s working. But here’s one of the most-promising indicators that things really could be changing in Japan. Women are coming into the workforce.

This is a huge development. Japanese women have traditionally worked far less than females in many other wealthy nations. Since the overall population is stagnant, pulling women into the labor force is one of the obvious levers the country can pull to boost the size of its labor force, and thus the productive capacity of the economy. Abe has famously claimed that Japan’s women are the resource-poor island nation’s “most-underutilized resource.”

“This is simply bigger than anything else Japan could have done,” said Adam Posen, president of the Petersen Institution for International Economics, at a recent conference on growth in the Asia Pacific region. Posen, a longtime student of the Japanese economy, argues that the addition of more Japanese women to the labor force actually is a double whammy. First off, it boosts the size of the labor force. But it also increases labor force productivity given the high levels of education of Japanese women. ”There’s been parity in education, but not parity in employment, so bringing women into the workforce raises the average skill level of the workforce,” Posen said.

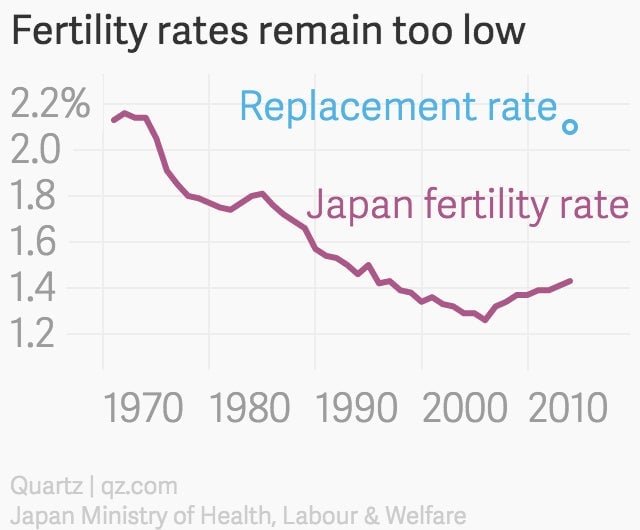

There is something of a catch, however. If everything else is equal, an increase in working women might result in a sharper decline in Japan’s already dire fertility rates, undermining any short-term gain from gaining women in the workforce in the first place. (While fertility rates have rebounded in recent years they remain below the roughly 2.1 level, which is needed to keep the population from shrinking.)

That’s because Japanese work culture is notorious tough to balance with family life. An employee who hopes to rise in a corporation is often expected to work between 10 and 15 hours a day. Combined with commuting and quasi-required afterwork socializing, that leaves little time for household work, the overwhelming amount of which is still done by women. (Japanese men do some of the least housework of men in any developed country.)

What’s the answer? Family-friendly policies are a good start. To that end the government has announced a plan to open up some 400,000 new childcare spaces in the country by 2018. (Long waiting lists are the rule right now.) And last year Japan made parental leave polices more generous and put new ones in place to try to encourage men to take leave.

But there’s a broader point. The fact is, Abenomics goes beyond economics. The effort to capitalize on Japan’s women underscores what a really important cultural shift the program is. And that includes major changes to soften the country’s notorious long-hours work culture.

Ironically, the health of Japan’s economy may depend not just on getting, and keeping, more women in the Japanese workforce, but on the Japanese workforce—as a whole—learning how to work a little bit less.