Behind the Chinese government’s brazen bid to pump up its stock market

China’s stock market soared once again today, with the Shanghai Composite climbing 4.7%, and sound economic news wasn’t the wind beneath its wings—manufacturing data were decidedly mixed.

China’s stock market soared once again today, with the Shanghai Composite climbing 4.7%, and sound economic news wasn’t the wind beneath its wings—manufacturing data were decidedly mixed.

The hero of the Chinese stock bonanza is, rather, the Chinese government. On Friday—a day after the market’s precipitous plunge—China’s central bank declared it wanted a “healthy” stock market, and leading state-run newspapers ran front-page articles proclaiming the bull market’s driving forces—monetary easing and economic reform—to still be intact.

Why are China’s authorities so brazenly talking up stocks? There are two main reasons, says Anne Stevenson-Yang of J Capital Research, a Beijing-based research group. In the near term, a continued bull market will funnel risk-free money to indebted firms, many of them state-owned.

“It allows companies to swap out debt for equity, because you don’t have to pay back equity, of course,” Stevenson-Yang tells Quartz. “It also creates a financing channel for companies that doesn’t require Chinese banks to [fund the equity-for-debt swap]. That’s the idea—’let’s get people to finance them.'”

The second goal, she says, is to maintain an alternative to the sluggish property market as a way for households to accumulate wealth. A rising stock market makes people feel wealthy again, even if their real estate assets aren’t appreciating like they used to.

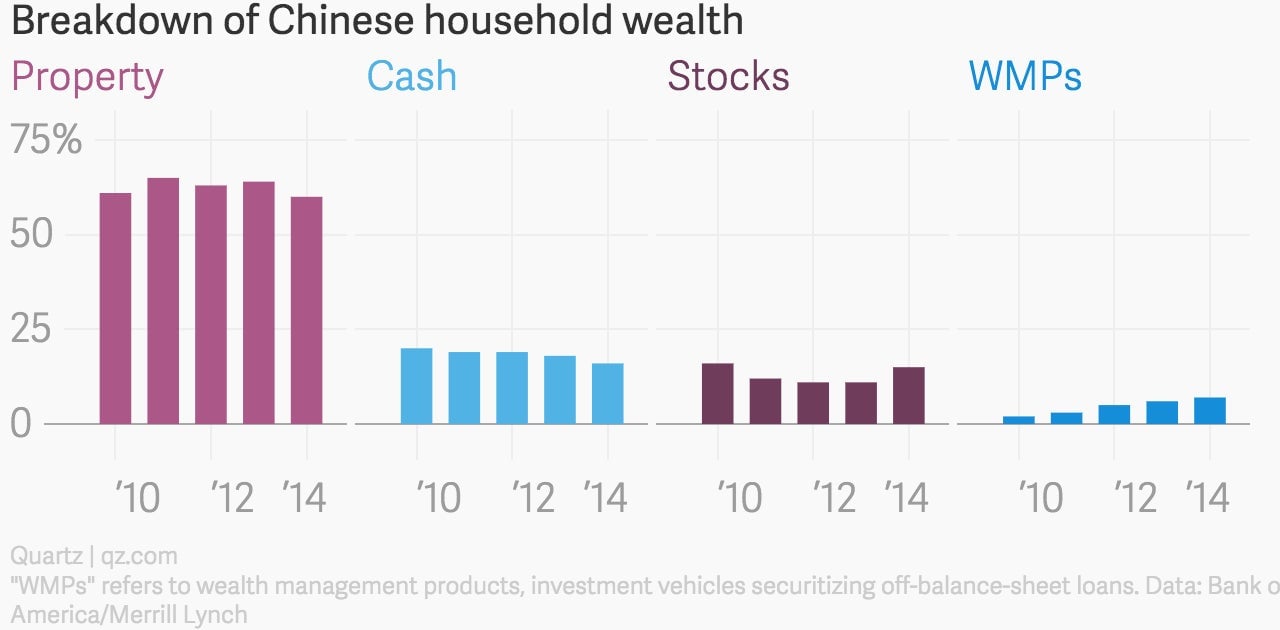

There aren’t many other ways for households to invest their money. The Chinese government bars all but the wealthiest citizens from investing outside the country, and it has long set artificially low interest rates. And until mid-2014, Chinese stocks were mired in a six-year-long bear market. That made housing the lone attractive commodity in which to store wealth—a trend that compounded itself as it drove prices higher. Chinese households hold about 13 trillion yuan ($2.1 trillion) in stocks, according to estimates by research firm Gavekal, but they’ve invested some 149 trillion yuan in urban housing. Bank of America/Merrill Lynch’s calculations differ a little from Gavekal’s, but they should give you a sense of the shift in where Chinese households store their wealth:

With more than two-thirds of their assets sunk into apartments, Chinese households’ sense of wealth—and therefore, their willingness to spend money—has hinged on home values. The sharp drop in property prices that began in 2014 has eaten away at that financial security—a big problem, given that the Chinese economy desperately needs consumers to spur demand.

State papers began talking up China’s stock market back in the summer of 2014, as the housing market was swooning. That support has recently grown even bolder. Zhou Xiaochuan, head of the People’s Bank of China, has been a particularly notable booster. As the market stalled in early March 2015, Zhou praised its fundamentals (link in Chinese) at two separate events. The Shanghai Composite closed out that month up 12%.

Another upside to the bull market is that it helps juice growth. As Gavekal’s Chen Long flagged in a recent note, the booming brokerage business helped add as much as 0.8 percentage points to China’s Q1 GDP. It also, he added, makes reform of state-owned companies much more profitable since Beijing can sell its shares at higher prices.

Of course, slashing debt and privatizing inefficient state behemoths are good things. But by hyping the market, the government is essentially urging its people to buy the stocks of companies with very weak—and in some cases possibly fraudulent—fundamentals. Last week’s selloff shows just how fragile China’s stock rally is. When the market finally reverses, it will be Chinese households who have ended up paying for the excesses of the state, once again.