Is India’s ultra-cheap Aakash tablet doomed?

According to a recent feature in the New York Times, India’s ultra-cheap Aakash 2 tablet, a $40 device on which Quartz has reported extensively, is an unmitigated disaster. Blown deadlines, business deals gone bad and broken promises are just a few of the accusations threaded throughout the piece. Yet the Times’ focus on the growing pains of an ambitious company underestimates its potential and, perhaps naively, slams a business pattern typical of companies wrestling with the problem of establishing high-tech supply chains in developing countries.

According to a recent feature in the New York Times, India’s ultra-cheap Aakash 2 tablet, a $40 device on which Quartz has reported extensively, is an unmitigated disaster. Blown deadlines, business deals gone bad and broken promises are just a few of the accusations threaded throughout the piece. Yet the Times’ focus on the growing pains of an ambitious company underestimates its potential and, perhaps naively, slams a business pattern typical of companies wrestling with the problem of establishing high-tech supply chains in developing countries.

As finished Aakash 2 tablets roll off final-assembly lines in India, perhaps this one piece hardly matters. After it was published, I reached out to Suneet Tuli, CEO of DataWind, maker of the Aakash 2 tablet. “The skepticism [in this article] probably helps us, as it keeps the 800lb guerillas [sic] away from this opportunity,” he said via email. And by 800 pound gorillas, he means electronics giants like Samsung and Acer, which has just announced its own inexpensive tablet.

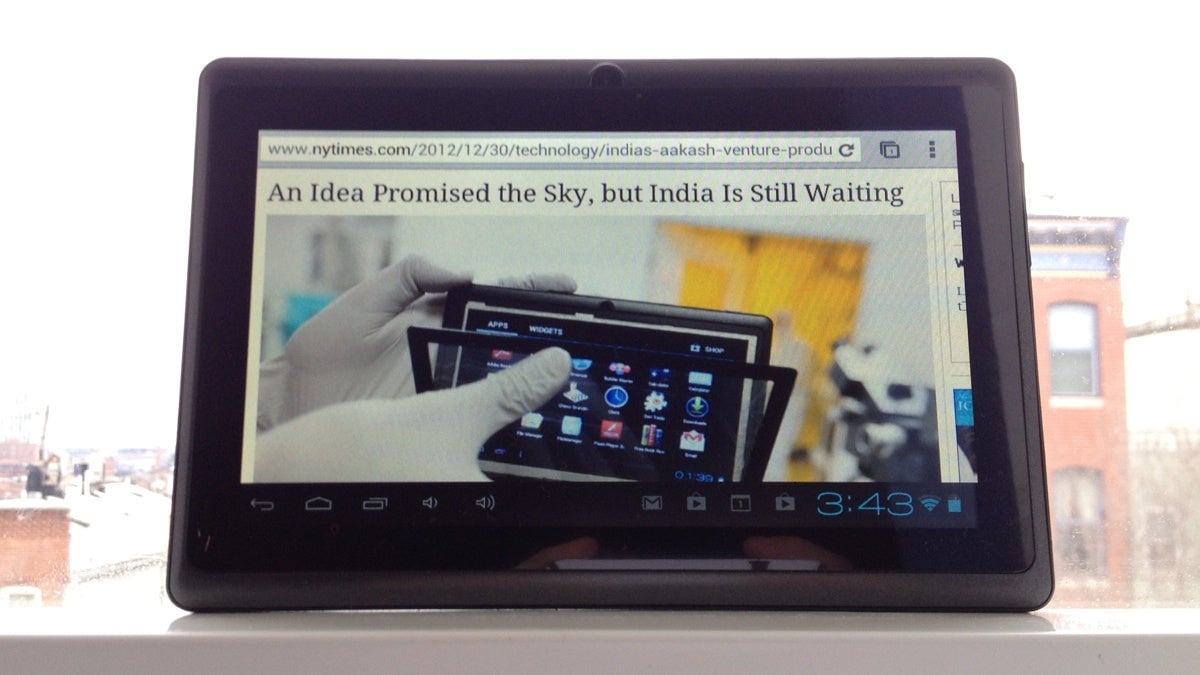

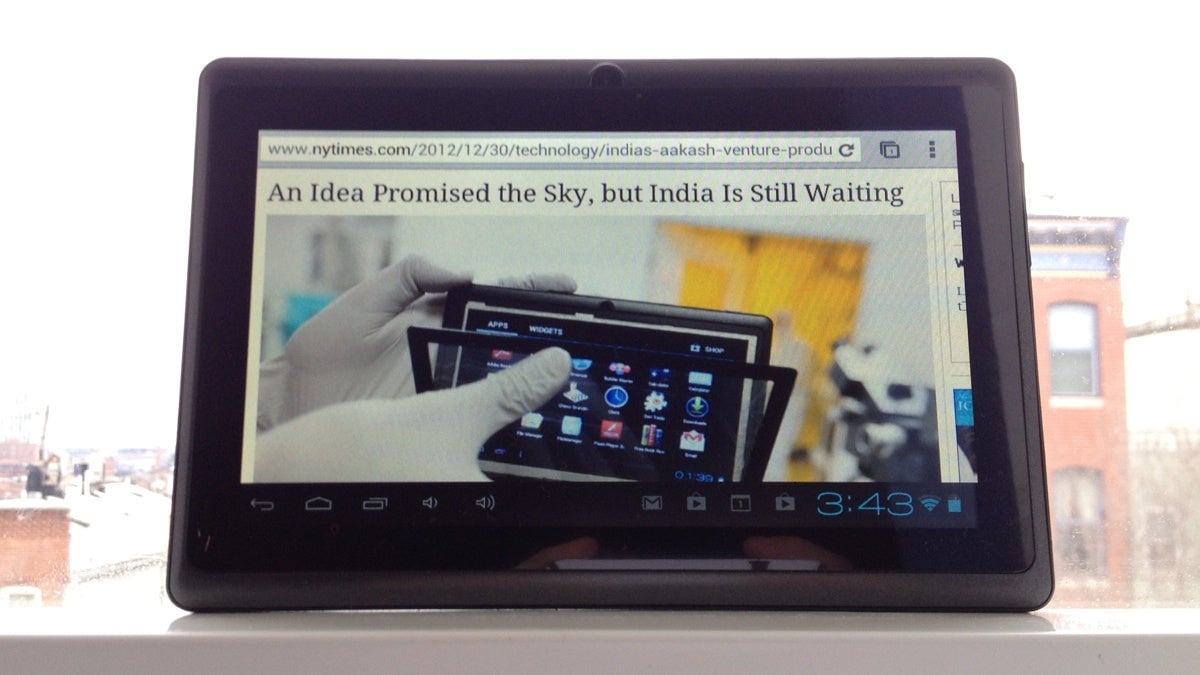

The fully-functional Aakash 2

For the most part, the Times’ piece failed to distinguish between the original Aakash tablet and the revamped Aakash 2 tablet, which is the one that has everyone so excited and which is to be delivered in a quantity of 100,000 to the Indian government. The original Aakash tablet, Tuli and others readily admit, was a disaster. Underpowered, it had an old-style resistive touch screen that made it almost unusable. (All modern touch-based devices, including the Aakash 2, have capacitative touch screens.)

I have been testing the commercial version of the Aakash 2 tablet, known as the Ubislate, and for its price it is a marvel of functionality. It’s a 7″ tablet with a processor about as fast as the one contained in the original iPad. Sure, it’s occasionally slow when compared to tablets costing 10 times as much, but it’s perfectly suited to be the sole computing device of a student in a developing country like India. And, as other reviewers have noted, it’s more than good enough to find a place in the homes of consumers in rich countries, as well.

In DataWind’s transition from the Aakash to the Aakash 2 tablet, we find a fairly typical arc for technology companies: Fail early, learn quickly, iterate until it works. But the Times reporters appear to have taken issues with the previous Aakash tablet as proof of some overall weakness in DataWind’s ability to execute.

Blown deadlines

The Times also notes that DataWind will not be delivering 100,000 tablets to the Indian government as originally planned, by Dec. 31. That deadline has been extended to March 31, however, as Tuli noted in an interview with the Times’ own India Ink blog. The Times reports that this delay represents a breach of contract, but Tuli says that’s false. “The article incorrectly states a year-end ‘deadline’ for the first 100,000 units – while IIT Bombay [one of the top engineering colleges in India] was targeting delivery by December end, there was no specific deadline or contractual requirement to deliver by then,” he said via email.

Manufacture in China vs. India

There has been some confusion, primarily in the Indian press, about how much of the Aakash 2 tablet can or should be manufactured in India. Here’s what’s going on: The Indian government never required that the the tablets it order be manufactured in India. As Tuli told me when we spoke in late November, the amount of manufacturing done in India is currently limited by the lack of electronics supply chains in the country. “We kit it in China and then we snap it together in India,” he said at the time. Which means that all of the the parts for the Aakash 2 tablet, from its sole circuit board to its case, are manufactured in China, then shipped to India as a “kit” which can be rapidly snapped and soldered together by relatively unskilled workers. Currently, the company directly employs between 50 and 60 workers in India, in addition to subcontractors.

DataWind also manufactures its own displays in a factory in Montreal, where the company is based, and Tuli says that eventually, a functionally identical “fab,” or fabrication plant for making the displays, will be set up in India.

In citing sources in China who are skeptical that India could ever have its own electronics supply chains, the Times misses the larger narrative: assembly of “kits” for consumer electronics is exactly how electronics manufacturing started in mainland China. Indeed, this is how complex supply chains have been seeded in Taiwan, South Korea and elsewhere: First, the most basic components are assembled in-country, and as local expertise increases, manufacturers and their subcontractors bootstrap their way up the value chain.

I have spoken with experts who attribute the entire “miracle” of Shenzhen, the Chinese city in which most of the world’s consumer electronics are manufactured, to exactly this sort of technological succession, starting with facilities identical to DataWind’s first tentative steps into the vicissitudes of manufacturing in a country as bureaucratic and fragmented as India. Finnish cell phone maker Nokia has already manufactured half a billion smartphones in India, in case anyone needs proof that India is no different from every other country when it comes to its potential as a manufacturer of high technology.

A small company, overwhelmed

The main thing the Times got right in its feature on the Aakash tablet is that DataWind appears to be a “small family company that was overwhelmed by a complex project that even China’s cutthroat technology manufacturers would find challenging to execute at the price expected by the [Indian] government.” DataWind has four million back-orders for its UbiSlate (the commercial version of he Aakash 2 tablet); the company is producing them as fast as it can, currently at the rate of some tens of thousands per month. Tuli has projected that in six to nine months, DataWind could be producing as many as half a million per month.

The demand for the Aakash 2 tablet has been so overwhelming precisely because DataWind was one of the first companies to take its margins to nearly zero, betting that the bulk of its revenue will come from advertising on the device and other services, such as a $2 a month wireless data plan.

The Times piece noted that “financial statements filed with British regulators show that the company is deeply in the red,” and left it at that. But when I asked Tuli about this, he said that “Apart from regular trade payables, we have no outstanding debt.” As is typical for young technology companies, DataWind has significant capital tied up in its build-out of manufacturing capacity and inventory. “The current order book is about $250 mil., which will generate reasonable hardware margins and significant recurring revenues,” he added.

Those “recurring revenues,” such as earnings from advertising on the millions of tablets DataWind will deliver, are one way the company plans to be able to continue to sell its devices at prices lower than its competitors. It’s an innovative business model, and a risky one: advertising in India is dominated by regional newspapers, and per-capita income in India has yet to exceed $1,000 a year. As with all technology startups, the probability that DataWind will fail is high. But it’s premature to write the obituary for a company that has four million orders for a perfectly functional product at a price that, as yet, no competitor can match.