Consumers really, really hated Keurig’s attempt to monopolize coffee pods

Less than a year ago, Keurig’s change in direction seemed like a masterstroke. After managing to weather unlicensed competition by signing up big coffee brands, and was set to solidify its position by introducing a new machine, the Keurig 2.0, that would make it impossible to use non-licensed pods.

Less than a year ago, Keurig’s change in direction seemed like a masterstroke. After managing to weather unlicensed competition by signing up big coffee brands, and was set to solidify its position by introducing a new machine, the Keurig 2.0, that would make it impossible to use non-licensed pods.

But early reports and reviews were less than enthusiastic. And now we’re seeing the results. Customers aren’t just complaining online. They aren’t buying the new machines, and inventory is piling up.

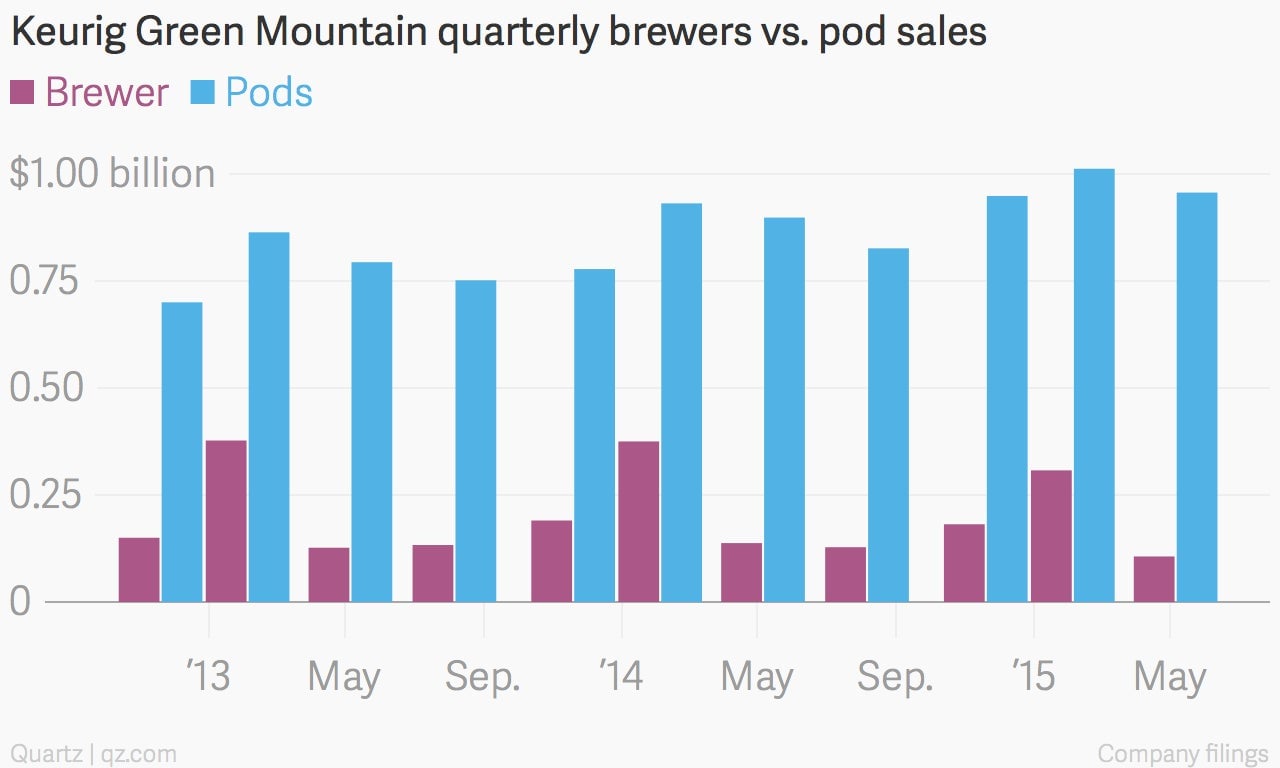

The number of brewers sold was down 22% from the same period a year earlier, after an already-weak peak holiday sales season, the company said last week. CEO Brian Kelley attributed some of this to “consumer confusion about pod compatibility,” in the company’s earnings call last week but it seems like people just aren’t fans. Shares are down about 10% since the earnings were revealed.

It’s acknowledging partial defeat in its efforts to protect its pod dominance that go into its machines, and will reintroduce “My K-Cup,” a company-manufactured device that allows people to use whatever coffee they like. Kelley admitted the error of his ways on the call:

We took the ‘My K-Cup’ away. And quite honestly, we were wrong. We underestimated, is the easiest way to say, we underestimated the passion the consumer had for this…. We shouldn’t have taken it away, we did, we’re bringing it back.

The company is admitting that it may have taken the monopoly thing a bit far. The issue thrust into the light by this is that Keurig isn’t really a coffee machine company. It’s a pod company:

The company hopes to turn things around by releasing a new brewer at a lower price point this summer, and prominently advertise the number of brands that the new Keurig brews.

Keurig’s success last year (it was, last August, the best performing stock on the S&P 500) came in large part in its ability to sign up brands like Starbucks and Kraft as licensed partners, giving it more powerful brands, more sales channels, and the ability to squeeze out third parties. Its sheer size helped, but so did the threat of the Keurig 2.0’s software lockdown. Keurig used retail partners to put an enormous amount of pressure on brands to sign up.

The negative reaction by consumers and slow sale of these machines means that it’s already starting to lose some of that leverage it allowed it to charge, on an actual coffee basis, around $50 a pound. The call pointed to weaknesses in the pod business. Digital sales were weak, as were sales at Dunkin Donuts stores. The company’s own brands have lost volume, and its price gap with other brands is increasing.

This isn’t just a bad quarter. It’s reopening the questions about the company’s pricing power and business model that had hedge-fund magnate David Einhorn actively betting on its failure until very recently. Keurig’s monopoly looks much less secure than it did just a few months ago.

This will also put extra and unwanted pressure on the company’s other new project—a machine for making cold carbonated drinks which prompted Coca Cola to take a big stake in the company.