The Fed’s balance sheet looks exactly like the Loch Ness monster

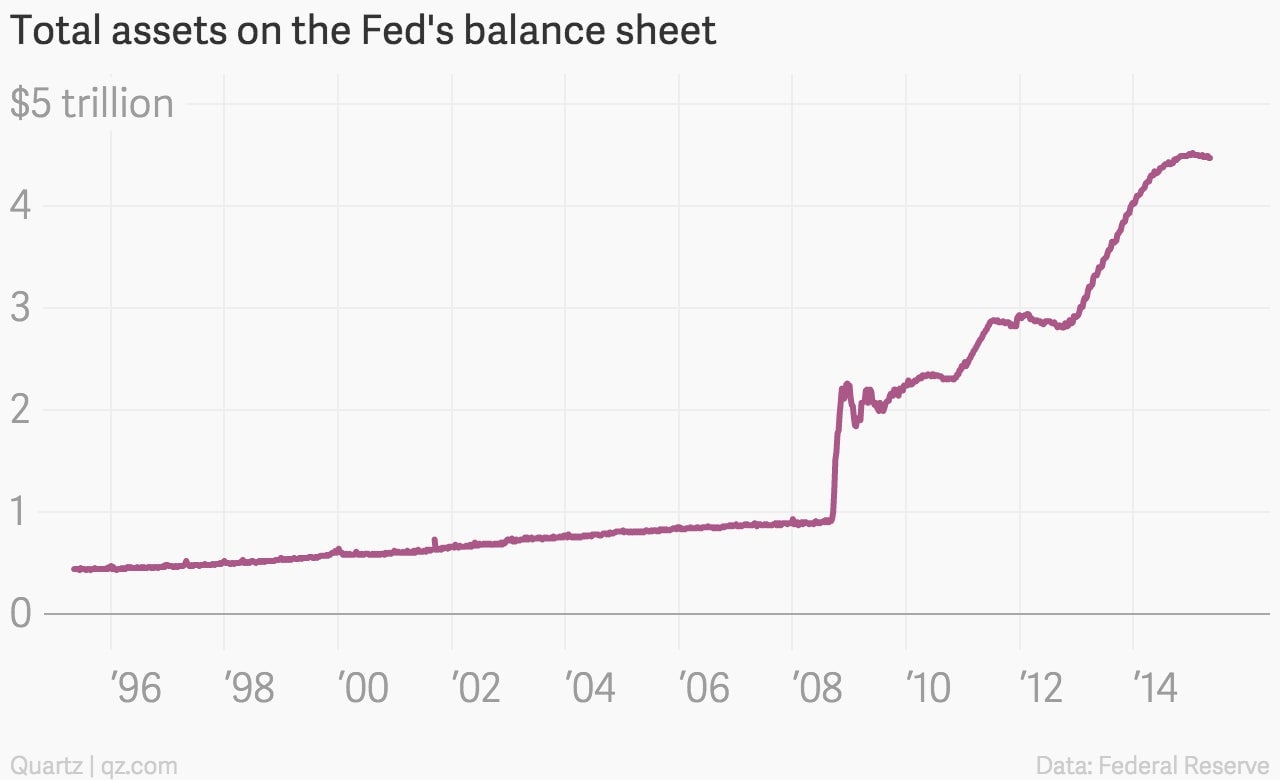

The Federal Reserve’s efforts to lower long-term interest rates have left it with a monstrous balance sheet.

The Federal Reserve’s efforts to lower long-term interest rates have left it with a monstrous balance sheet.

The balance sheet, by which we mean securities—mostly US government bonds—owned by the central bank, has climbed to $4.5 trillion over the last few years.

Why? Because the Fed is doing its job. By law the US central bank is supposed to work to maximize employment and maintain price stability. With job growth so weak in recent years, and benchmark, short-term interest rates about as low as they could go, the central bank started hammering away at the long end of the yield curve. It bought up a ton of longer-dated bonds, with the hopes of creating enough scarcity to drive up prices and bring down yields. People have argued that this process, known as “quantitative easing,” didn’t work fast enough. And indeed it took several iterations of various bond-buying programs before the economy seemed to finally click into gear.

But more recently things have come to a head, so to speak. Over the last year the Fed tapered off its bond-buying program, leaving its balance sheet with the distinctive, graceful neck and furtive alertness of Scotland’s most-famous possible plesiosaur. Like people who see the visage of the divine on a grilled cheese sandwich, technical analysts often see meaningful shapes in charts.

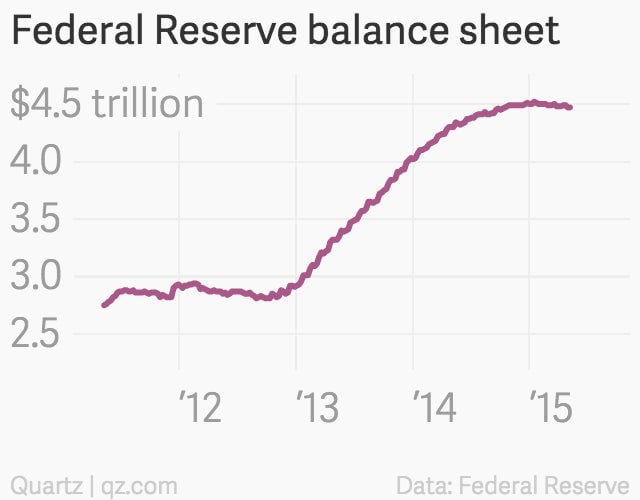

But something important is actually happening here. If we zoom in on the head of the beast, and you squint pretty hard, you can see that Fed’s balance sheet peaked back in January 2015 at $4.52 trillion and is actually beginning to shrink ever so slightly. (It was $4.47 trillion in the most recent report.)

This may come as a surprise to all those eagerly waiting for word that the Fed is raising interest rates. But the fact is, the long, slow, slog back to a more-normal Fed has already begun.