To fight antibiotic resistance, we may have to pay the hugely profitable pharma industry even more

Despite the fear that resistance to existing antibiotics may soon kill millions every year, the pipeline of new antibiotics has seen a long-term decline.

Despite the fear that resistance to existing antibiotics may soon kill millions every year, the pipeline of new antibiotics has seen a long-term decline.

The solution to this paradoxical problem, set out in the latest report from the Antimicrobial Resistance Committee, is to form an international body that will revitalize research in antibiotics and award pharmaceutical companies billions for developing new antibiotics.

What is not clear, however, is that why should governments pay money to an already-profitable pharmaceutical industry to spur innovation.

Feeding the rich?

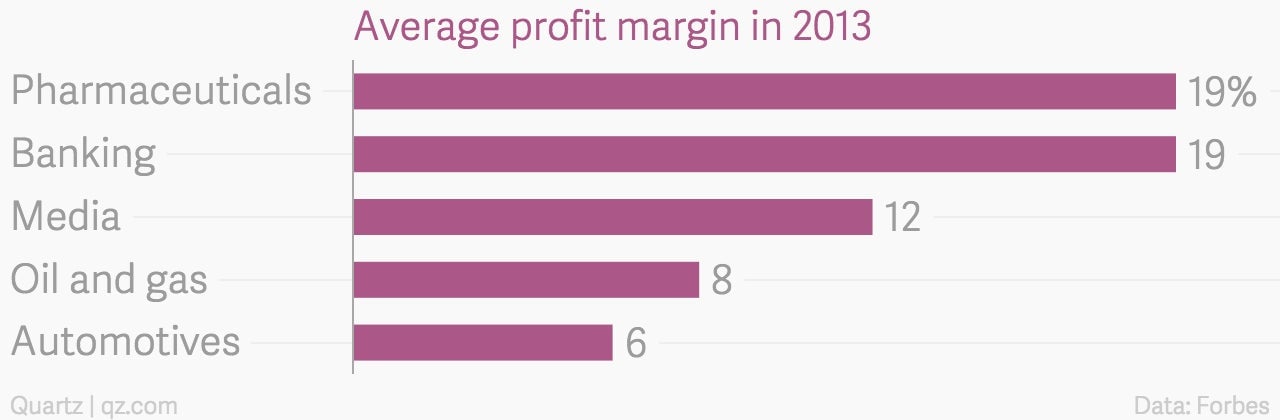

In 2013, the top 10 pharmaceutical companies put together made about $90 billion at a profit margin of 19%. It is already clear that Big Pharma, as the top giants are known, is only interested in working on the diseases that reap large rewards. So if antibiotic resistance is going to affect the rich and poor alike, then doesn’t Big Pharma already have the incentive to invest in developing new antibiotics?

Not really, John McConnell, the editor of the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases, told Quartz. Unlike cancer drugs, infectious diseases have never had “revenue potential.” McConnell argues that spurring innovation on finding infectious-diseases drugs usually requires external motivation.

An example of such external motivation is the successful public-private partnership, Gavi. This is how Gavi works: first, countries that are eligible for Gavi’s support submit proposals for what kind of vaccines they require. Next, Gavi organizes funding conferences where both rich and poor countries fork out money towards the cause. Gavi then uses that money to pay pharmaceutical companies to either research those vaccines or guarantee bulk purchase.

Between 2000 and 2008, the number of deaths from measles fell from 750,000 to 164,000 because Gavi organized vaccine immunizations.

Learning from examples

In 2014, UK prime minister David Cameron set up the Antimicrobial Resistance Committee, chaired by Jim O’Neill, the former chief economist of Goldman Sachs. In the committee’s third report, O’Neill suggests replicating the Gavi model for helping develop and procure new antibiotics.

He needs such an international body because, even if antibiotic resistance is going to affect both the rich and the poor, the revenue potential for new antibiotics is estimated to remain low.

Unlike a diabetes drug that patients are required to use for a long time, antibiotics cure infections and therefore sales are low. Additionally, many of them still work for treating common infections. And, anyway, it was the excess use of antibiotics that accelerated drug resistance.

Without new antibiotics, O’Neill predicts that the cumulative cost to the global economy by 2050 could be as much as $100 trillion. (For comparison, the total global GDP in 2014 was some $77 trillion.)

He suggests that we could buy ourselves out of an antibiotic-resistant world by investing about $40 billion in research over the next 10 years. This money will be doled out to create a market and also provide a reward for the return on Big Pharma’s investment.

To make this happen, the investment required from each country as part of a global alliance would be small. If O’Neill is right, this pharmaceutical lottery ticket could have a huge pay-off.