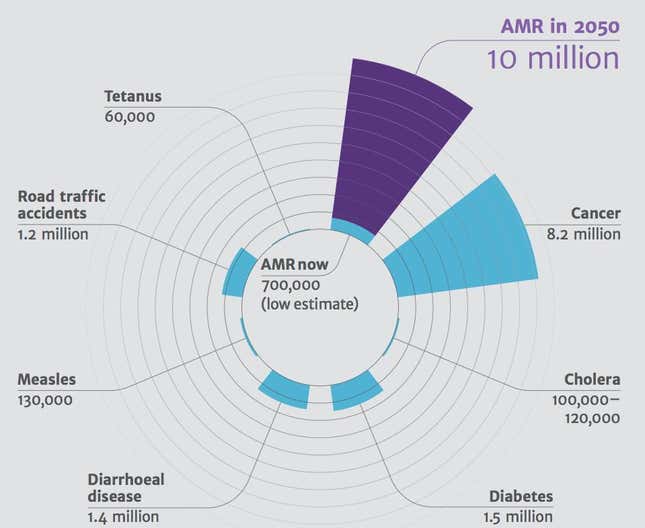

A scourge is emerging across the rich and poor worlds alike, one that will claim 10 million lives a year by mid-century. Watch out for the “superbugs”—pathogens that even antibiotics can’t kill. Between now and 2050, this plague will claim 300 million lives and drain up to $100 trillion from the world’s GDP.

That’s according to a new report (pdf) on the emerging antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis by the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, a non-government advocacy group. Commissioned by British prime minister David Cameron in 2013, the project is led by Jim O’Neill, the former Goldman Sachs economist famed for coining the acronym ”BRICs.”

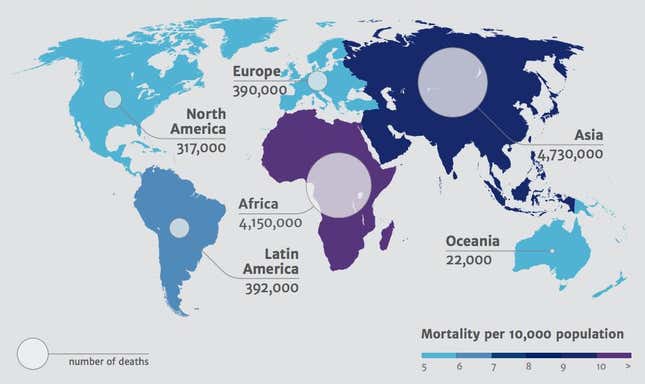

AMR now kills 23,000 Americans (pdf, p.6) a year, and 25,000 in the EU (pdf, p.vi). But data elsewhere is sparse. Worldwide, the Review puts the annual death toll at 700,000.

The report says the biggest killer will be malaria resistance, which as an article in Science notes, has already emerged in Southeast Asia. Nations like China and Brazil that have successfully eradicated malaria will likely see that effort unravel, hurting their export sectors.

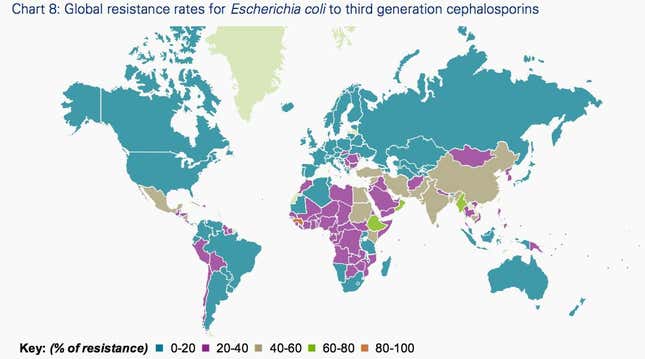

However, E. coli will put the biggest dent in GDP, says the report. Meanwhile, many parts of Africa will face with the compounding double-whammy of HIV and TB. Rich countries will suffer too; the OECD faces cumulative losses of up to $35 trillion.

These calculations, which synthesize scenarios modeled by consulting firms RAND Europe and KPMG (pdf), are based on woefully sparse data. But the Review’s effort is also the first time a prominent group has given a body-count and dollar-value sense of the post-antibiotic world that awaits us if we don’t take ”coherent international action.”

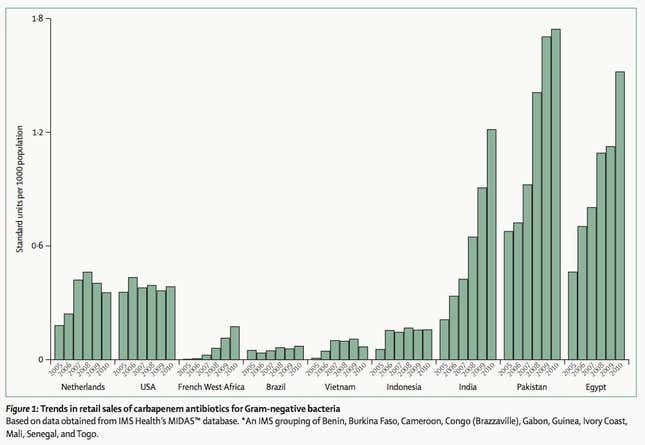

Globalization means that superbugs created by one region’s antibiotics abuse spread easily to areas where they are used more responsibly, as infant-killing superbugs (paywall) in India exemplify.

In that sense, antibiotics are a public good, argued leading researchers in The Lancet. And because they’re incredibly hard to develop—and since that research has ground to a halt—antibiotics are now largely a non-renewable resource.

Not everyone supports O’Neill and company’s work. In an editorial (pdf), The Lancet criticizes the report for “not being as scientifically rigorous or informed by evidence as one might hope.”

The Review concedes this point. Lack of data and forecasting necessitated big assumptions—for example, RAND’s calculations assume that all drugs eventually fail, while KMPG assumes infection rates double.

Neither is as far-fetched as it might sound, though. And their research only modeled the impact of three bacteria—Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escheria coli and Staphylococcus aureus—and malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV. They also only modeled output losses, not healthcare costs.

The 300 million estimate also doesn’t count the zillions of procedures that antibiotics make possible. Include mortality from procedures antibiotics make possible—e.g. Caesarean sections, cancer therapies, joint replacements, and organ transplants—and AMR will shave close to 7% off global GDP, a cumulative $210 trillion, says the report.

That math is pretty fuzzy. Then again, the closest the World Health Organization has gotten to quantifying economic impact is that AMR slashes GDP by 1.4-1.6% (pdf, p.15)—without projecting the future toll. And without hard numbers on AMR’s future economic and health impact, the problem is too easily dismissed as an abstraction—making “coherent international action” is unlikely.