China plans to be the first to land on the dark side of the moon

The Pink Floyd album aside, the “dark” side of the moon is not actually dark—it receives just as much sunlight as the hemisphere of the moon that we can see from Earth. It’s “dark,” because it’s mysterious, as it has never been explored by humans before.

The Pink Floyd album aside, the “dark” side of the moon is not actually dark—it receives just as much sunlight as the hemisphere of the moon that we can see from Earth. It’s “dark,” because it’s mysterious, as it has never been explored by humans before.

Until now, that is. Wu Weiren, the chief engineer for China’s Lunar Exploration Program, told Chinese Central Television (link in Chinese) that the country is planning to land its Chang’e-4 probe on the moon’s “dark” side. “We probably will choose a site that is more difficult to land and more technically challenging,” he said, according to GBTimes. “Our next move probably will see some spacecraft land on the far side of the moon.”

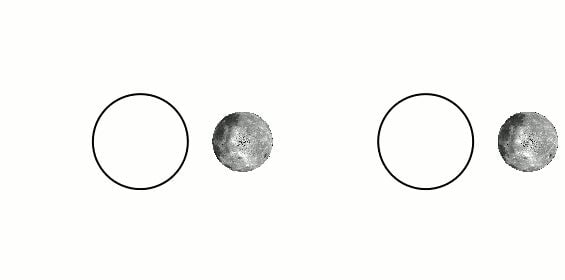

The reason that the dark, or far, side of the moon, never faces Earth is a phenomenon known as ”tidal locking.” Over the course of millions of years, the Earth’s gravity slowed down the moon’s rotation, matching it to the speed of its orbit.

The Soviet probe Luna 3 was the first to photograph the dark side in 1959, and astronauts on the Apollo 8 mission were the first humans to see it with their own eyes. Since then, it’s been photographed by various probes, most recently by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (which snapped the image at the top of this story).

Chang’e-3, Chang’e-4’s predecessor, landed on the moon in 2013. It was the first spacecraft to do so safely since the Soviet probe Luna 23 in 1976.

The Chang’e-4, set to launch in 2020, will orbit the moon before sending a rover down to the lunar surface—possibly, if all goes according to plan, on the unexplored far side for the first time ever.

NASA has mulled sending spacecrafts to the moon’s far side, but so far has no plans to do so. Not only is it logistically difficult, but it would be far more expensive than landing on the near side of the moon. In any case, NASA seems focused on getting to Mars, not revisiting the moon. Been there done that.

Not only is China attempting to flex its space muscles with Chang’e-4, it also wants to win the battle over the moon’s resources—particularly water and helium-3.

In addition to being a good spot to place radio telescopes (because it avoids transmissions to and from Earth), the far side of the moon could be a geologist’s dream. The South-Pole Aitken Basin, a massive impact crater on the far side, may contain parts of lunar mantle, which could then help scientists understand a lot more about the interior of the moon and how it was formed.