Hey, average American, here’s how you benefit from free trade

Free-trade agreements touch so many different aspects of the market that their consequences can be difficult to predict.

Free-trade agreements touch so many different aspects of the market that their consequences can be difficult to predict.

Most Americans are aware of one of the nastier potential side effects: off-shoring, and the impact this has on American jobs and wages. Less recognized is that when companies hire or set up factories abroad to take advantage of cheap labor elsewhere, Americans’ real income goes up because a lot of the stuff they’re buying is cheaper.

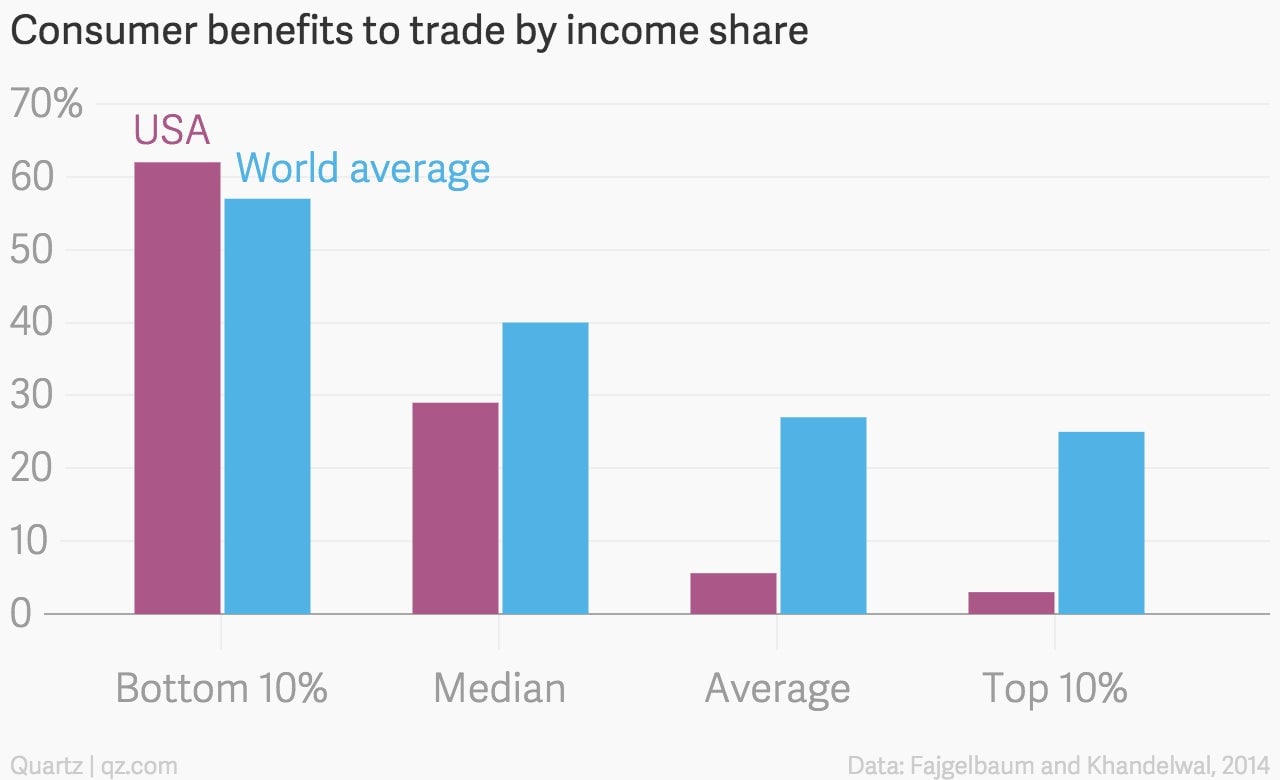

In fact, some economists estimate that thanks to trade, average consumers in the US are 5.6% better off than they would be otherwise, in terms of real income. And because Americans who earn less money purchase more consumer goods, as a share of their total income, than the wealthy, they actually benefit disproportionately.

This chart, based on data from a 2014 working paper (pdf) from the National Bureau of Economic Research, shows the benefits to real income that have accrued to consumers in different income tiers, both in the US and worldwide, as a result of international trade.

The economists who developed this model, Pablo Fajgelbaum and Amit Khandelwal, find that the benefits to the top 10% of earners are more significant to those outside the US, mainly because the highest-earning Americans tend to make a lot more money than the highest earners elsewhere, minimizing the effect that trade would have on their real income.

The question is: Does the overall cost-of-living benefit from cheaper goods make up for the potential hit to wages? Khandelwal says he is unaware of any single study doing that direct comparison, but he does note that a paper using a similar methodology (pdf) to model the effects of international trade finds that worldwide, trade has increased the earnings of skilled workers by 8%, while increasing the real incomes of the bottom 10% of earners by 32%. Those outcomes would vary country to country, though, making it difficult to pinpoint whether the benefits exceed the costs to American workers.

In terms of the debate over the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the 12-nation trade pact that US president Barack Obama wants the country to sign onto, the research suggests that lowering trade barriers helps low-income Americans more than critics of free-trade deals let on.

But don’t mistake it for a straight-up analysis of the TPP. Every trade agreement comes with its own peculiar set of terms, and though trade-related gains to low-income consumers are real, they potentially could be outstripped by the benefits accruing to higher earners—mainly in the form of share price appreciation for multinational companies and an increased wage premium for highly-skilled workers, both of which would disproportionately reward people in higher income tiers.

In any case, if the TPP goes through, it will be a lot easier to measure the negative effects than the positive ones.

“There’s a 10th percentile person that exists in every part of the country, but there might be one factory that shuts down,” Khandelwal tells Quartz. In that sense, ”the losses from trade are very apparent and very focused, [while] the gains tend to be diffused across an economy.”