The key thing to know about Obama’s big trade deal

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visits Washington this week, and he hopes to come back with strengthened ties to his country’s largest ally—including, perhaps, improved prospects for a free trade deal promoted by US President Obama that would link Japan to the US and eleven other nations.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visits Washington this week, and he hopes to come back with strengthened ties to his country’s largest ally—including, perhaps, improved prospects for a free trade deal promoted by US President Obama that would link Japan to the US and eleven other nations.

Critics of the Trans-Pacific Partnership argue that TPP isn’t actually a trade deal. And they emphasize their worries about common standards the deal aims to set on issues like corporate-state relations and intellectual property give short shrift to the needs of poor at the expense of big business.

But TPP is very much a trade deal, even though it goes beyond traditional efforts to reduce tariffs in trying to ease the way into foreign markets. And that’s most clear when it comes to Japan, one of the few major US trading partners without a free-trade agreement; their participation alone bumped up estimates of annual US income gains by $52 billion.

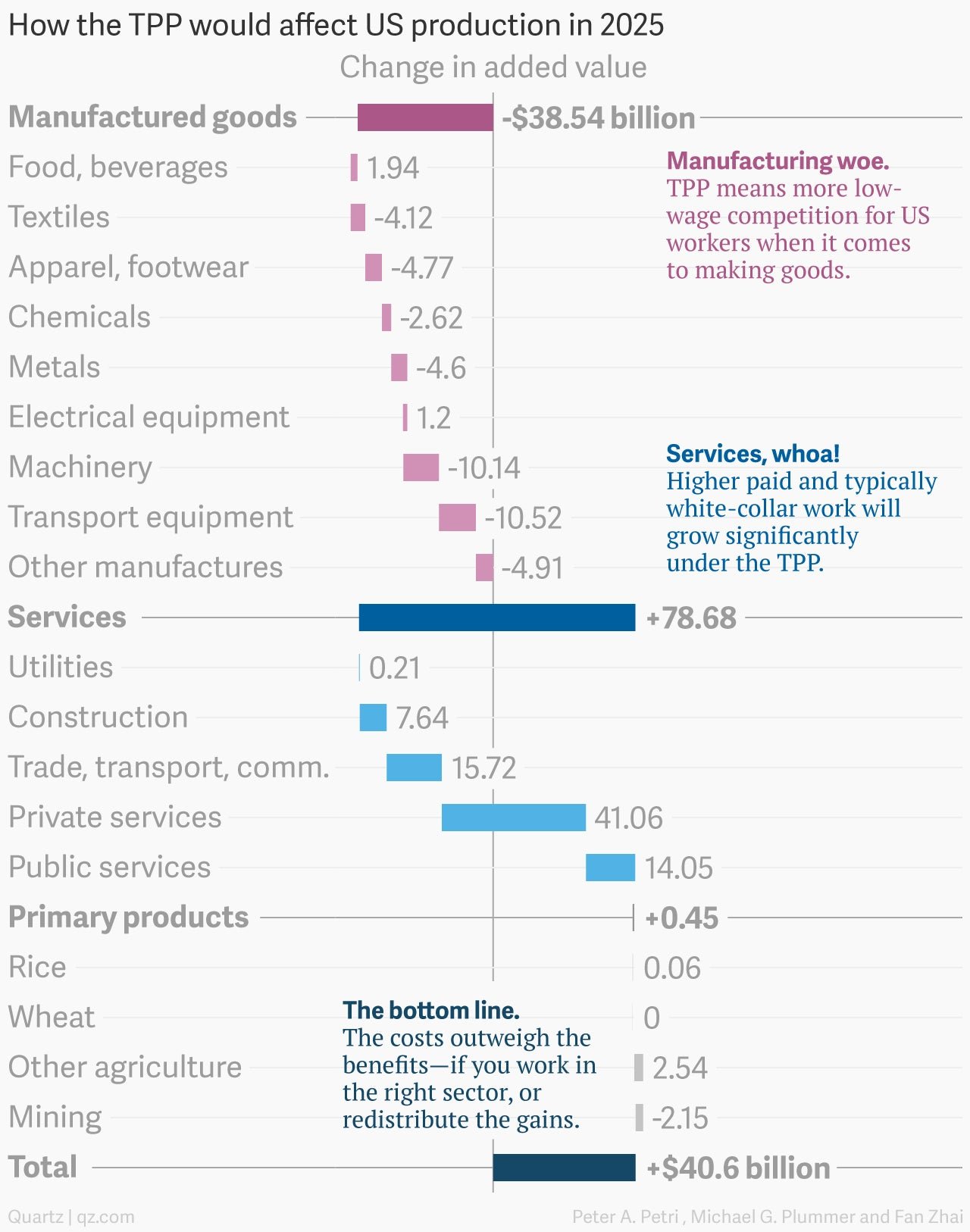

Economists who’ve studied the TPP think that US exports will likely rise as a result of the deal. But it can be a bit misleading just to look at total export numbers, which can rely on goods partially made abroad. To get a sense of why there is so much division over the bill, consider the measure of “value added” as way to help understand—it shows how much US labor and capital enhances something. That can be a product—say a bunch of car parts come from Mexico, but a GM worker puts the final vehicle together, adding value to the finished goods—or a service—an Apple designer adds value to a product by dint of creating its appearance and an Apple software designer, its functionality. But the iPhone or iPad is manufactured abroad.

If you measure the change in “value-add” by sector, relative to what economists think would happen under the current US set of trade policies, it helps explain how the TPP would change the US economy come 2025:

What’s clear is that the TPP would continue to accelerate the trend in the US economy that’s long been in place. For decades, the economy has been tilting away from manufacturing and toward professional services that require more skills. The TPP would, in effect, double down on that strategy creating higher-paying jobs for some, but at the expense of lower-skilled manufacturing jobs that have been shrinking for a long time.

The researchers—economists from Johns Hopkins and Brandeis among them—behind these estimates assume that TPP would, over five years of implementation, result in 40,000 to 50,000 workers annually looking for new job in each of the first three years. That would rise to 100,000 annually in the final two years. That’s a relatively small part of a labor force of more than 160 million, but it’s still a significant number of humans facing economic dislocation. It also bolsters critic’s arguments that, without efforts to share the gains of trade more broadly, the deal could exacerbate economic inequality.

Abe faces a similar conundrum at home: While joining the accord will require rolling-back protections on Japan’s politically-powerful agricultural sector, it will also give Japan’s stagnant economy access to demand from new markets, offering the potential for re-invigoration.