Fancier clothes aren’t that much better for the environment than fast fashion

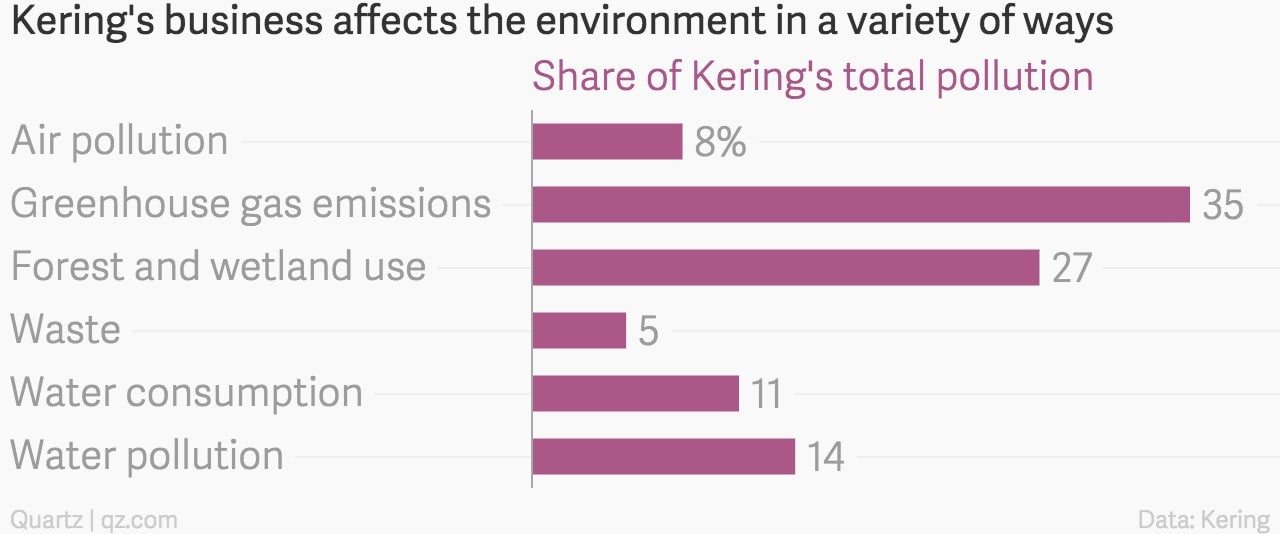

Making large volumes of clothing is an inherently dirty business—mainly because of the way the raw materials are produced and processed. Cotton, for instance, is a notoriously water-intensive crop (pdf), and tanning leather can have disastrous effects on the areas where it’s done and on the workers who do it.

Making large volumes of clothing is an inherently dirty business—mainly because of the way the raw materials are produced and processed. Cotton, for instance, is a notoriously water-intensive crop (pdf), and tanning leather can have disastrous effects on the areas where it’s done and on the workers who do it.

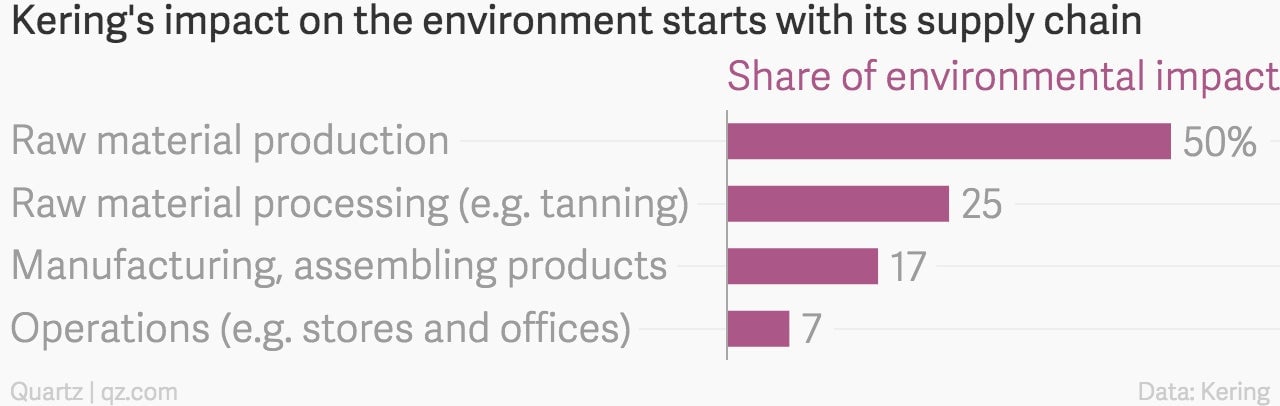

That’s why the first ever “Environmental Profit & Loss” report from the luxury fashion group Kering to cover all its brands—Gucci, Saint Laurent, and Stella McCartney, among others—shows that the vast majority of the company’s environmental impact comes early in the supply chain.

The report (pdf), which collected and analyzed data from more than 1,000 suppliers in 126 countries at every step of the production process, offers some valuable insight into the effect a fashion conglomerate has on the environment. While it highlights Kering’s commitment to reducing its environmental footprint—it notes that without the steps it has taken, Kering’s impact would be about 40% greater—it also demonstrates the challenges of doing so.

That three-quarters of Kering’s environmental impact comes from just producing and processing the materials to create its goods underscores an important point: The more clothes Kering makes with these materials, the greater its environmental impact will be. It’s a similar issue to the one H&M faces, where despite making genuine efforts to clean up its practices—such as switching to organic cotton—just the sheer volume of organic cotton used by the fast-growing, fast-fashion retailer is part of the issue. (But a distinction drawn by luxury goods makers such as Kering is that their products are meant to last, which already makes them more sustainable than mass-manufactured apparel.)

Both H&M and Kering are working to address resource use—and are even doing it together. They’ve teamed up with Worn Again, which has developed an innovative technology for recycling textiles, to help shift the industry away from virgin resources and toward using more recycled fibers.

To counter the pollution produced by its supply chain, Kering says, the company seeks out responsible sources and monitors some suppliers, even helping them access financing to improve their efficiency. According to Kering’s report, 25 of the textile mills it sources from are part of the Natural Resource Defense Council’s inventive Clean by Design program, which works with Chinese mills to cost-effectively reduce their infamously severe impact.

The report frames all of this information as something like a financial balance sheet. As Kering explains, it ”is a means of placing a monetary value” on the changes in wellbeing to people caused by “the environmental impacts of a given business along its entire supply chain.” It’s the method used in the Natural Capital Protocol Project, which seeks to give businesses a common basis for measuring their environmental impact. In 2013, the year Kering’s report covers, the value of Kering’s effect on the Earth was €773 million ($861.6 million).

Since the Natural Capital Coalition doesn’t make the impacts of its other members public, it’s difficult to compare Kering’s performance with that of other companies. That’s part of the reason Kering says it shared its report publicly. It says it wants to influence other companies to do the same and “to catalyse others, in both the private and public sectors, to identify and manage their impacts on natural capital.”

Hopefully it works.