Fashion is a dirty business, and the process of dyeing and finishing textiles is a particularly filthy part of it. It uses a lot of energy and water, as well as toxic chemicals with disturbing side effects such as causing hormone imbalances in wildlife. These chemicals can easily end up in a mill’s wastewater, contaminating nearby lakes and rivers.

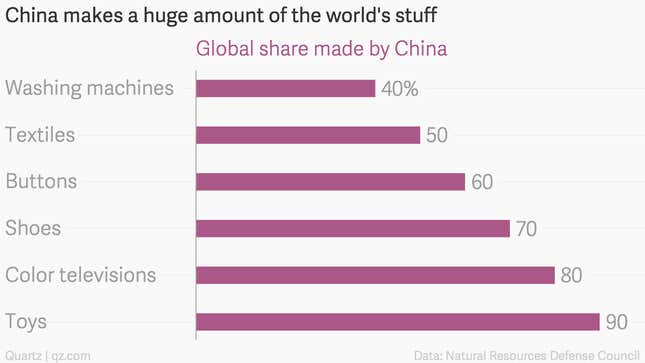

China is the global epicenter for manufacturing, producing an astounding amount of the world’s stuff. It is also an ecological nightmare due in part to its lax oversight of industry. China’s State Environmental Protection Administration reports that nearly a third of the country’s rivers are classified as too polluted for any direct human contact (link in Chinese).

Textile mills are a huge part of that, but the mills themselves have little incentive to change without some clear financial benefit. An international environmental advocacy group is trying to offer that incentive.

Six years ago the New York-based non-profit Natural Resources Defense Council launched Clean by Design, a program focused on getting Chinese textile mills to clean up their practices by emphasizing the financial savings they can reap and using large retailers, which are some of these mills’ main customers, to apply leverage. The retailers who have signed on are Target, H&M, Levi’s, and Gap, and in the last two years Clean by Design has finally come up to scale, as NRDC puts it.

In 2014, 33 mills in Shaoxing and Guangzhou completed the program, which requires the mills to implement various measures devoted mostly to improving efficiency. According to a new report by the organization, which details the projects and results at each mill, the mills not only reduced their environmental footprints, they fattened their bank accounts as well.

On average, each mill cut its water use by 9%, electricity use by 4%, and coal use by 6.5% through relatively simple fixes such as improving insulation and boiler efficiency, routinely measuring water and electricity consumption, reusing resources, and capturing heat discharged by hot water—what Linda Greer, director of NRDC’s health and environment programs, calls “the low-hanging fruit.” The savings added up across the mills. NRDC estimates they saved 3 million tons of water, 36 million kilowatt-hours of electricity, 400 tons of chemicals, and 61,000 tons of coal.

The mills saved a total of $14.7 million, and the mill with the single highest gains saved $3.5 million, according to the NRDC’s figures. It projects that the five-year savings for the mills will be $56 million.

Greer says showing the financial benefits is important as there’s no better way to get mills to improve their own practices than seeing another mill benefit from the changes. For the program to make a real dent in China’s pollution, it needs to spread without the NRDC’s help, since China is home to an estimated 15,000 textile mills.

Greer admits there’s a significant problem that the program can’t easily fix: the use of hazardous chemicals. When the mills dye fabrics, their business depends on getting the colors right for their clothing label clients—which is why they’re reluctant to change their practices.

The program also doesn’t address a fundamental problem: the sheer amount of textiles it takes to create the massive volume of clothing the mills produce. Responsibility for that falls on the retailers placing the clothing orders, and it’s one of the biggest issues fashion faces where sustainability is concerned.

Still, cutting back on the use of water and energy, particularly carbon-emitting coal, is worthwhile, and if China’s textile mills realize that going green can also be financially beneficial, it’s a win for everyone.