Google’s moronic portrayal of designers is no laughing matter

Let’s hope that Google’s new video about its so-called design philosophy is a glitch.

Let’s hope that Google’s new video about its so-called design philosophy is a glitch.

Premiered at its annual developer conference in San Francisco last week, the purpose of the seven-minute video was to explain Google’s visual framework called Material Design. But instead of providing clarity and context, the video finds delight in showcasing a cast of its designers muttering half-formed thoughts and lapsing into non-sequiturs like a stylized blooper reel. Only in this case, no-one is laughing.

While the series of outtakes may be a cute trope, like a segment from The Office, Google’s video serves to undermine these highly-skilled and accomplished designers. They’re presented as aesthetes with a limited vocabulary toying with fuzzy metaphors, unable to explain a theory they came up with a year after launch.

It’s easy to dismiss Google’s seven-minute production as yet another example of indigestible goopy lasagna of marketing nonsense, but the video actually inflicts great harm to all designers with the stereotypes it perpetuates.

Designers should know their own history

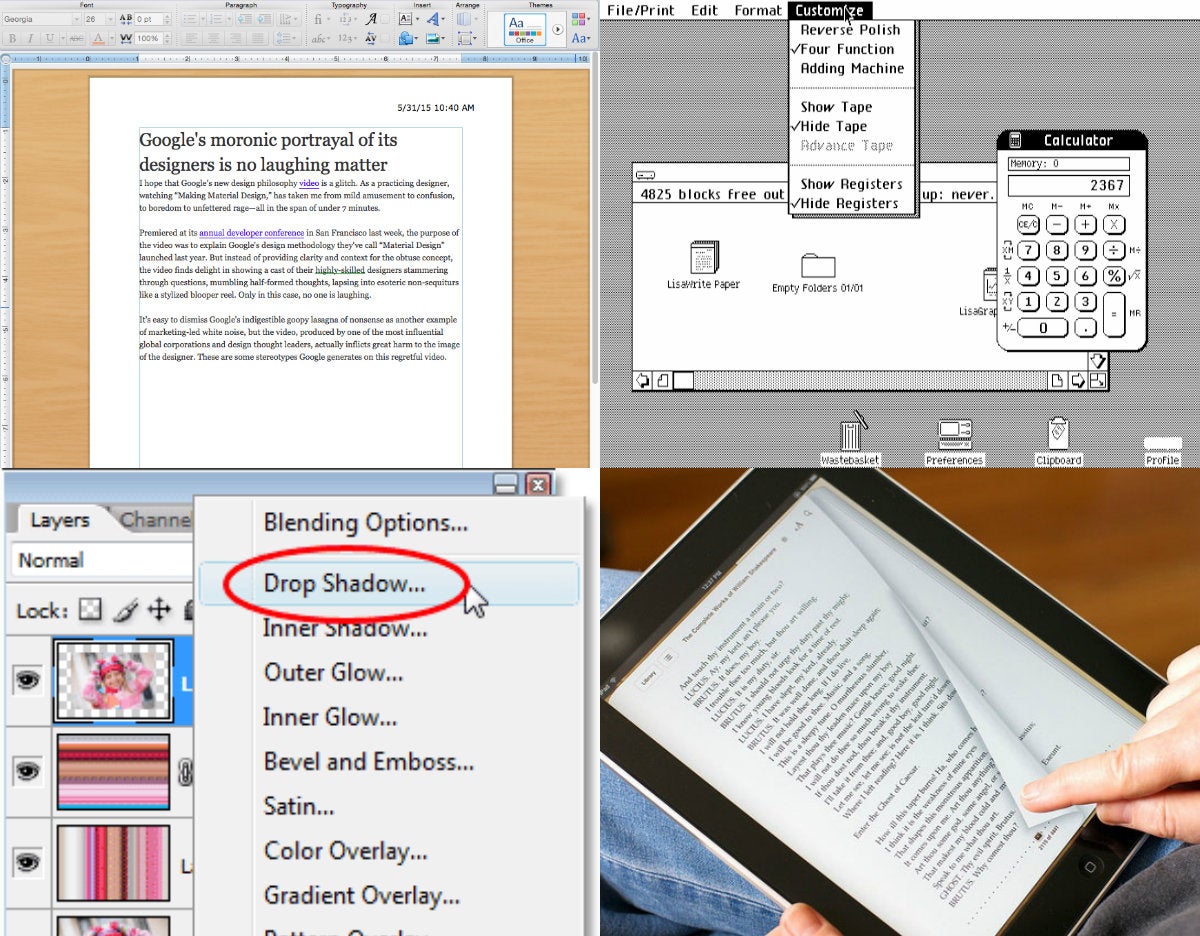

To imply that Google invented interaction design or drop shadows is a joke. Perhaps the most egregious part about the video is the portrayal of Google’s intelligent designers as complicit with this cone of ignorance.

They are shown as self-referential, oblivious to their own history and the science behind their work. “Jon [Wiley] came up with the idea he describes as quantum paper in order to create these rich, tactile interfaces,” gushes Google vice president of design Matias Duarte, promptly negating the whole history of design, art, and technology.

“In the early days, we were going out and trying experiments,” muses Wiley about Material Design’s creation, which dates back about 12 months ago. Google’s principal designer is wearing artsy silver frames, a dark T-shirt similar to Apple chief design officer Jony Ive’s signature attire, and something on his wrist that looks like an Apple Watch.

The designer credited with revolutionizing Google’s Search function with Google Instant and autocomplete is also a former improv comedian and often referred to as the company’s funniest person. But in this video, he is shown to be humorless and sincerely milking the gravitas of the moment. If this was meant to be a parody, it’s a poor one and an inside joke nobody got.

History check: Material Design is essentially a facet of interaction design, a specialization concerned with the user’s behavior and well established since the 1980s by pioneers like Bill Moggridge and Bill Verplank.

And to suggest that Google’s design team is the first to study surfaces and shadows is a stunning gaffe. Surely Google is aware of its many predecessors. The desire to emulate 3-D tactile objects in flat computer interfaces exists in Microsoft Office, Adobe Photoshop, ebook readers, and even in Lisa, Apple’s first personal computer with a graphical user interface. Legendary German interface designer Kai Krausse wrote the manual on gaussian blur shadows more than 20 years ago.

Google’s Material Design approach may be an evolution or a refinement, but surely not an invention. If the video producers had only consulted Google Books, they might have stumbled upon these resources: Industrial design history, Bill Moggridge, Haptics, Trompe-l’œil.

But what’s the big deal?

It matters because Google’s short clip is foundational to the evolving definition of design itself. With design’s scope being so broad and specializations so specific, it’s already hard for designers to explain to the rest of the world what they do exactly.

It’s worrisome that the general public or even young minds thinking about future careers will eventually Google the word “design” and find this motley crew as the top result. The prospect that this could very well be the default portrayal of a designer is dreadful—a disservice to the legions of thoughtful, well-read, opinionated, and articulate designers in all fields working in the real world.

Since its founding in 1998, Google has advanced the field of design in the most profound ways—giving the world smart, accessible, and thoughtful tools, not to mention regular doses of delight and adventure that stretch human potential. Even the spirit behind Material Design is commendable: providing free resources for developers who are strong on coding but lacking in core graphic design skills. But the communication campaign around it is a blunder and an error message on a grand scale.

The design world deserves a correction and an update.