Early on June 3 last year, India’s rural development minister, Gopinath Munde, was on his way to New Delhi’s airport. At around 6.20 AM, as he neared the Aurobindo Marg-Tughlak Road intersection in the heart of the city, a speeding cab crashed into his car. The 64-year-old minister died hours later—the only casualty in the accident—due to an internal injury.

Jolted out of its usual complacency with this high-profile incident, India’s nine-day-old government led by prime minister Narendra Modi swiftly promised reforms.

“In a month’s time we will re-draft the Motor Vehicle Amendment Bill in sync with six advanced nations—USA, Canada, Singapore, Japan, Germany and the UK,” India’s transport minister Nitin Gadkari said, “and thereafter will introduce it in parliament.”

A year later, nothing much has changed.

The promised Road Safety and Transport Bill, 2014, which was to replace the existing Motor Vehicles Act 1988 is stuck in a regulatory logjam—apparently held up by powerful lobbies—even as road accidents continue to kill more than 100,000 people every year in India.

Deadly roads

In the past decade, 1.2 million Indians have died on the country’s roads.

In 2013 alone, over 443,000 road accidents were reported in India (pdf) with 147,423 deaths as a result (pdf). India has the deadliest roads in the world, with one person dying every five minutes in an accident. And this could rise to one death every three minutes by 2020.

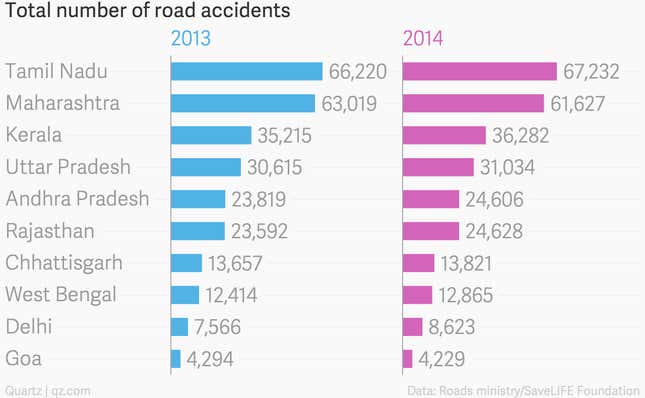

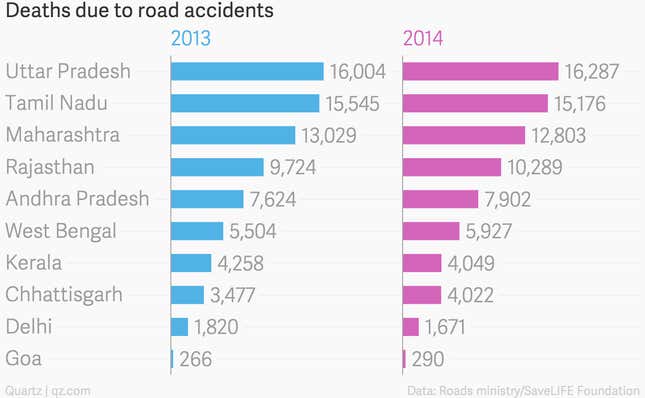

The statistics for 2014 are just as gory, according to data from the road ministry procured by New Delhi-based road safety advocacy group, SaveLIFE Foundation.

Moreover, it is often India’s young and middle-aged who are most susceptible to deaths on India’s roads. Last year, as many as 35% of those killed were in the 30-44 years category. The 15-29 years category accounted for 31% of the total deaths.

The annual socio-economic cost of these accidents, India’s now defunct Planning Commission estimated in 2014, could be around 3% of the gross domestic product. By that estimate, the cost of road crashes in the country would amount to Rs3.8 lakh crore ($60 billion).

Empty promises

Two months after Munde’s death, in September 2014, the Modi government provided an outline of the new road safety bill, with a range of harsh punishments for rash driving and even imprisonment for faulty manufacturing designs by automakers. The bill also had a provision for setting up of an independent agency to regulate vehicles and road safety.

After ten months, three revisions and many meetings with stakeholders, those tough punishments now stand significantly diluted in the fourth version of the bill that emerged in February.

Among others, the latest bill has reduced the fine for over-speeding from Rs15,000 to Rs2,000 for the first offence. Similarly, penalty for failure to comply with standards for road design, construction and maintenance was reduced from Rs10 lakh per person killed to Rs1 lakh. The bill also proposed a cap of Rs15 lakh for insurance claims towards death and disability caused by road accidents.

On April 30, transport unions in at least eight states went on a strike to protest the measures proposed in the new road safety bill—and demanded a diluted version.

“That new bill could have changed things,” explained Piyush Tewari, founder of the SaveLIFE Foundation. “There are too many lobbies that have been working against the bill. The automotive industry, the truckers, the insurance companies and road construction companies.” The non-profit is now campaigning for the prime minister’s direct intervention.

The Society of Automobile Manufacturers, the National Highway Builders Federation, and the General Insurance Council—industries that Tewari claims have been lobbying against the bill—did not respond to emailed questionnaires from Quartz.

And now, Tewari argued, with India’s new government—as part of its effort to hasten economic growth—wanting to build 30 kilometres of highways a day, the lack of effective safety regulations could mean even deadlier roads.

“Statistics suggest that there is one death in every two kilometres,” he said. “Adding 30 kilometres a day will mean that 15 more people will die everyday.”