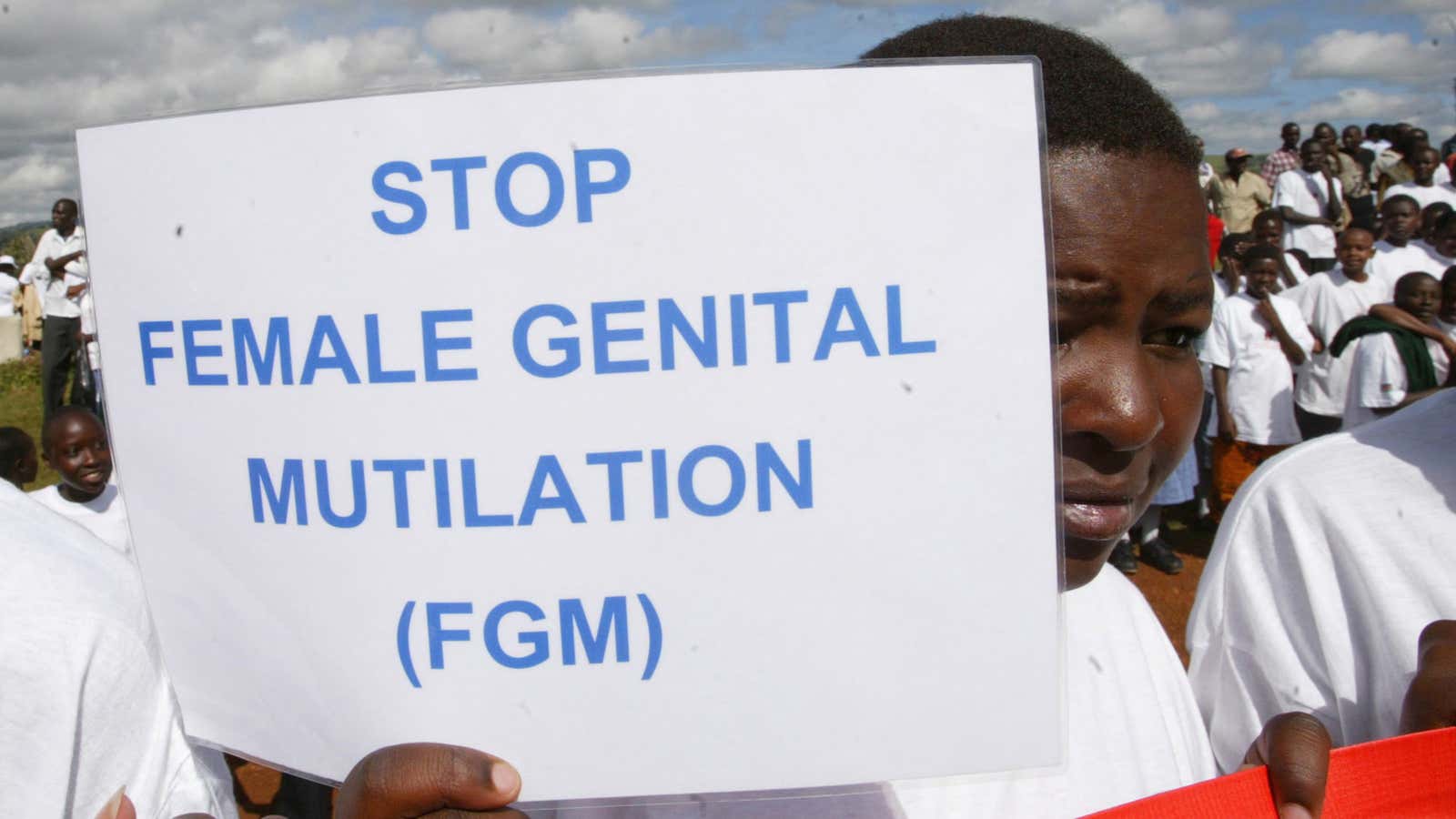

In a move welcomed as a step in the right direction by international advocates, outgoing Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan has signed a bill officially banning the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM). The Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act 2015, which was passed by the Nigerian Senate earlier in May, also will prevent men from leaving their families without proving financial support, according to Reuters.

The United Nations defines FGM (also sometimes referred to as female genital cutting, or FGC) as “all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” Globally, an estimated 100 million to 140 women and girls from nearly 30 countries have undergone the procedure, with the highest rates concentrated in Africa and the Middle East. In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, UNICEF reports that around 27 percent (almost 20 million) of women and girls ages 15-49 have been cut.

Although at times inaccurately characterized as a specifically Muslim custom, FGM actually pre-dates Islam and carried out by followers of a variety of religions, including Islam, Christianity and Judaism. Practitioners often defend the practice by arguing it is traditional rite of passage, but opponents such as Amnesty International consider it a form of violence against women, and have linked it to a variety of medical problems.

So far women’s advocates have generally expressed optimism in the wake of Jonathan’s 11th hour action, but they caution that legislation alone will not be enough to eradicate a practice so deeply-rooted in familial and ethnic customs. Real change must be cultural, not merely political.

“We welcome this ban as we welcome any ban on FGM, in any country,” Tarah Demant, senior director for Amnesty International USA’s identity and discrimination unit, tells Quartz. “But it’s unclear whether other countries will do the same.”

Demant said that any legislation that recognizes violence against women as unacceptable is a move in the right direction, but it remains to be seen how the new law is implemented and enforced, which may ultimately determine its effectiveness. “We are hopeful this ban will be [coupled] with educational outreach to ensure women have access to their health rights, and are free from violence,” she said.