Why Britain ranks at the bottom of the charts in high-tech industrial production

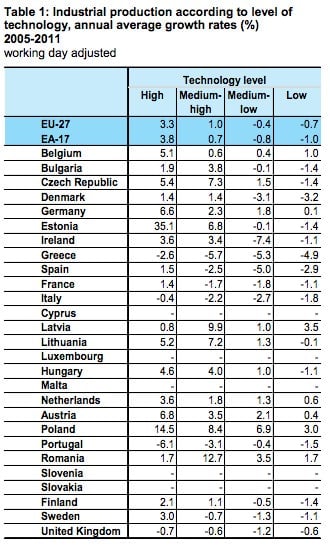

Though still reeling from a financial crisis and the economic fallout, the European Union’s high-tech manufacturing increased 26% from the beginning of 2005 through to the third quarter of 2012, according to Eurostat’s index of indicators (pdf), while industrial production as a whole only just returned to 2005 levels. Though many EU countries saw average annual growth rates for high-tech industrial production soar during that period—for example, Estonia’s and Austria’s grew 35.1% and 14.5%, respectively—EU stragglers like Greece, Italy and Portugal all posted negative growth.

Though still reeling from a financial crisis and the economic fallout, the European Union’s high-tech manufacturing increased 26% from the beginning of 2005 through to the third quarter of 2012, according to Eurostat’s index of indicators (pdf), while industrial production as a whole only just returned to 2005 levels. Though many EU countries saw average annual growth rates for high-tech industrial production soar during that period—for example, Estonia’s and Austria’s grew 35.1% and 14.5%, respectively—EU stragglers like Greece, Italy and Portugal all posted negative growth.

Oh, and the UK, whose 0.7% average annual decline in high-tech production left it third-worst in the EU, lower even than debt crisis-crushed Italy.

What gives, Britain? For one thing, the problem isn’t new. In a 2010 report commissioned by Prime Minister David Cameron, British industrialist and vacuum tycoon James Dyson spelled out (pdf) a strategy to make Britain Europe’s “leading generator of new technology.” But there’s a lot of ground to make up, pointed out Dyson: between 1970 and 2003, the UK “suffered the sharpest decline in manufacturing as a share of total employment of any advanced economy.” Dyson recommended putting a greater emphasis on promoting science and engineering in business, industry, education and public culture. However, so far there’s little evidence that Dyson’s recommendations have been heeded.

Eurostat’s data suggest the same—and hint that investment is at least one major reason that the UK is losing still more ground to its European neighbors. The analysis looked at R&D expenditures in relation to value added by high-tech industries, including the manufacture of computers, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and air and spacecraft machinery.

A shortage of highly-skilled technology workers is another problem. Dyson warned yesterday “of a deficit of 60,000 engineering graduates this year and urged the government to do more to attract the brightest into engineering and science,” reports the Financial Times (paywall).

This is hardly surprising considering the state of math and science education in the UK. A report at the end of December 2010 showed that the UK was becoming mathematically challenged, as fewer than one in five students in England, Wales and Northern Ireland took advanced math courses after the age of 16, compared to 50%-100% of students who take advanced math past that age in EU countries such as Estonia and the Czech Republic. Data on science education from last December is similarly grim: out of 50 countries, Britain tumbled to 15th place in 2011, down from seventh in 2007. In short, expect that gap between the UK and its more successful high-tech neighbors to widen.