Like most right-thinking people, I don’t condone corruption and abhor anyone responsible for ruining the integrity of the game that we love.

But a troubling narrative has emerged out of the FIFA corruption scandal.

The story starts with the suggestion FIFA chief Sepp Blatter had been able to maintain his stranglehold at the top of world football due, primarily, to his influence over the “smaller” nations in the game. He acquired this influence, the argument continues, by bribing officials from these small nations who in turn guaranteed him the votes he needed to stay in power.

To fix the game, the ‘big nations’ needed to assert themselves with FIFA, so the argument goes. Greg Dyke, the head of the English Football Association (FA), suggested that the Europeans should’ve seriously considered pulling out of FIFA, if Blatter won another term. Michel Platini, the president of UEFA, echoed his sentiments saying that, “enough is enough” and refused to rule out his members boycotting the next World Cup.

The implication here is clear: the “smaller” nations’ (read Africa and Asia) undue influence is corrupting the game. To fix it, the ‘big nations’ (read Europe, and to a lesser extent South America) need to take football back. “The great danger now is you get Blatter Mark II. That’s the danger. It needs a root and branch change of the structure of the organization,” Dyke said after Blatter stepped down this week.

Yes, the Swiss-born Blatter may be corrupt. But the manner in which he diluted the European influence on the game partly explains why there’s such vehement hatred of him in the region. For example, he helped institute a rule that rotated World Cup hosts through the six continental federations.

The change allowed Korea and Japan to host the tournament, as Asia’s representatives, for the first time in 2002. And in 2010, the tournament finally came to Africa. By all accounts the 2010 World Cup in South Africa was a huge success. This policy, which may soon be reversed, did not necessarily sit well with the game’s traditional elites. But it explains why Blatter is so loved in Africa and Asia. He’s also widely acknowledged for championing funding to support football development and infrastructure in many of these nations.

Here’s the Nigeria Football Federation president Amaju Pinnick, talking to the BBC this week: “Blatter feels Africa, he sees Africa and he has imparted so much – a lot of developmental programmes.

“Without Blatter we wouldn’t enjoy all the benefits we enjoy today from Fifa. What Blatter pushes is equity, fairness and equality among the nations. We don’t want to experiment.”

Taking back the game

Now that Blatter is gone, the talk is of this being a chance to overhaul FIFA. The suggestions of reforms have included doing away with the one country-one vote system for presidential elections, to be replaced with something that gives more weight to countries with higher GDPs. Another option that has been mooted is to award votes based on the number of players registered with a country’s FA. Unsurprisingly, this approach will skew power very heavily towards the European nations.

The rhetoric following the scandal, to me and others, suggests a concerted effort to try and re-orient the power of football away from the so-called “micro-states” to what some believe to be the game’s true home: Europe.

Too late, I’m afraid.

Football’s spirit has not been purely European for a long time now. A brief cursory glance at the top leagues shows just how non-European the game has become. Barcelona, who play Juventus on Saturday for the Champions League title, have as their strike force three South Americans. Yaya Toure, who led the English Premier League’s Manchester City to the title last year, is from Cote d’Ivoire.

Overall, close to 26% of players currently playing in Europe’s “Big 5” leagues are from non-European countries, according to data from sportingintelligence.com. In fact, the best player in the world right now is a 5ft 7 magician from Argentina by the name of Lionel Messi. All this does something to the spirit of the game. And it ain’t European.

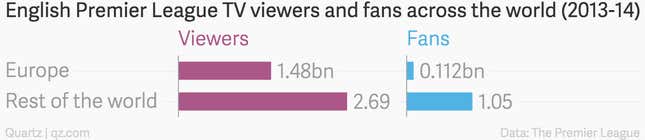

If you look at the global audience for the game–which the leagues leverage for huge advertising dollars–most of the eyeballs are watching from outside Europe. So the idea that the game’s spiritual home is in Europe, when an increasing share of its financial strength is because of non-Europeans, is a little silly. The English top league for example, boasts an audience of close to half a billion in Africa alone, data from the Premier League shows.

So it’s time that Europe recognizes that football is no longer just European. It is African, it is South American, it is Asian and it has become global. And for the lovers of the game, it is better for it.