John Paulson’s single gift to Harvard nearly equals the whole endowment of America’s richest black school

While everyone on the internet (Quartz included) was going on and on last week about John Paulson’s $400 million gift to Harvard University, Howard University was busy getting its bonds downgraded by Moody’s.

While everyone on the internet (Quartz included) was going on and on last week about John Paulson’s $400 million gift to Harvard University, Howard University was busy getting its bonds downgraded by Moody’s.

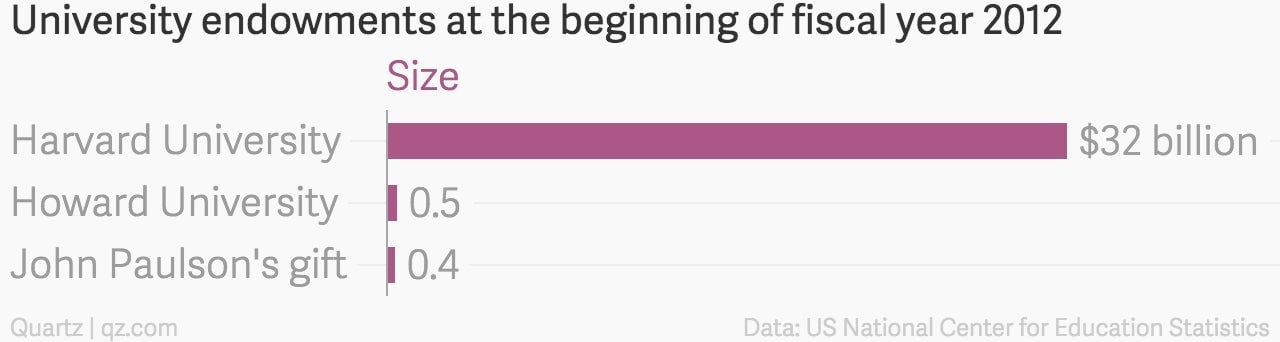

It’s a sad bit of irony. Howard is sometimes considered the Harvard of historically black colleges and universities (a category that has its own acronym in America—HBCUs). But the two events lay bare the inequality between the two schools. Even though Howard is the richest of the HBCUs, it is struggling through painful budget cuts. More strikingly, as NPR’s Gene Demby notes, Paulson’s $400 million gift alone is larger than the entire endowment of almost every single HBCU in the country. Howard is the only exception:

So if the billionaires of the world want to put their money into education and avoid accusations of deepening inequality, their dollars would probably go much further at black schools.

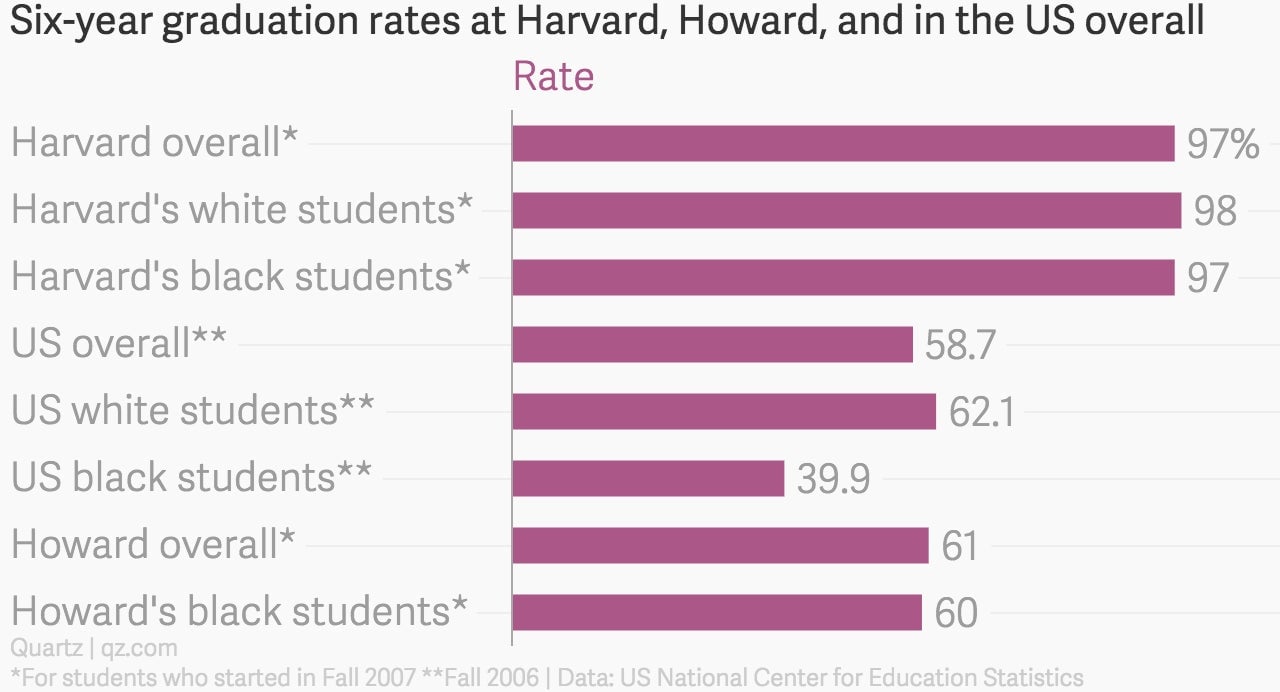

To see why this is, it’s worth keeping in mind that overall, four-year schools in the US do a terrible job of graduating black students at the same rate as their white peers. Though black students at Harvard have six-year graduation rates on par with the school’s 97% rate overall, that’s far from the norm.

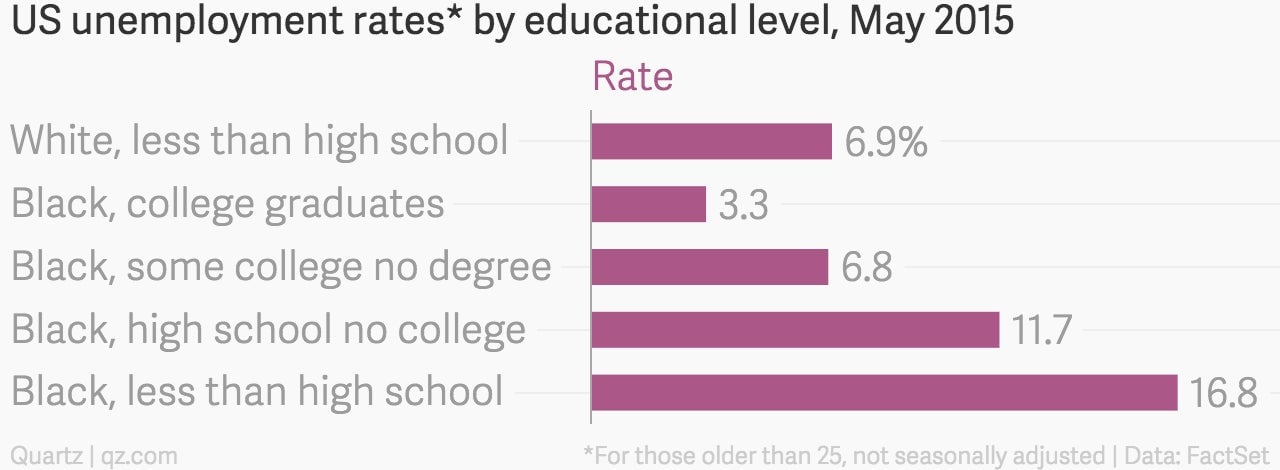

Howard, on the other hand, graduates black students at a better rate than the national average for all students. Moreover, HBCUs have an explicit mission of educating black students, a very direct form of reducing inequality. College-educated black people, after all, are one of the few groups of black people older than 25 with a better unemployment rate than white high school dropouts.

More black graduates means more black people in the labor force who can earn better salaries at jobs that require college degrees, more money for gifts to their schools, and fewer black people constrained to the lowest rung of America’s economic ladder. They also graduate a disproportionate number of black engineers, which is why Google has been reaching out to them to solve tech’s diversity pipeline problem.

Now, a common, and tempting, argument against giving to HBCUs on the same scale as to Ivy League schools is that they can’t manage the money they already have. And it’s definitely true that HBCUs have a tough time with money. Most of the reasons Moody’s cited when it downgraded Howard were financial, and the vice chair of the school’s board of trustees wrote in 2013 that the school would close in three years if it couldn’t get its books together.

But it’s not only the school’s management that is to blame. Combine fiscal dysfunction with a lack of money in the bank with shrinking enrollments, and shaky federal funding in the form of student loans, and it’s easy to see how things could come to a head quickly.

By no means would money alone be a perfect salve. The super-rich would also need to help HBCUs fix the problems previously described. And they’d need to hire their graduates. Then they’d need to help those graduates with their disproportionately high student loan burdens. Of course, none of that is as fun as writing a big check and basking in the headlines.