This post has been corrected.

In his opening remarks at the African Union summit this past weekend, chairperson and Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe questioned why African leaders should have term limits. He likened the two-term limit to a “rope around the neck” for African leaders, adding that European leaders do not face the same term limits, yet are considered full democracies.

It is ironic that the nonagenarian should question term limits in his seventh term as president (but his first under Zimbabwe’s new constitution, which restricts him to two). Some dismiss his comments as the confused ramblings of a man out of touch with reality—after all, in the same opening remarks he poked fun at Burundian president Pierre Nkurunziza’s bid for a third term in office. His comments are equally ironic given that Zimbabwe’s new constitution imposes a two-term limit, a provision Mugabe himself endorsed.

He may not be the most credible authority on the question of term limits, but if we set that aside for a minute, could he have a point? After all, as Mugabe rightly points out, having term limits does not necessarily make a country democratic.

Democracy is understood to be synonymous with frequent changes in government, and term limits are a convenient way to make that happen. But what if the people want the president back for a third term? Isn’t it undemocratic to prevent the people from expressing this preference because of term limits? At its core, that is what Mugabe’s comments were about. Are term limits truly not a “rope around the neck” of leaders whose people want them to continue serving?

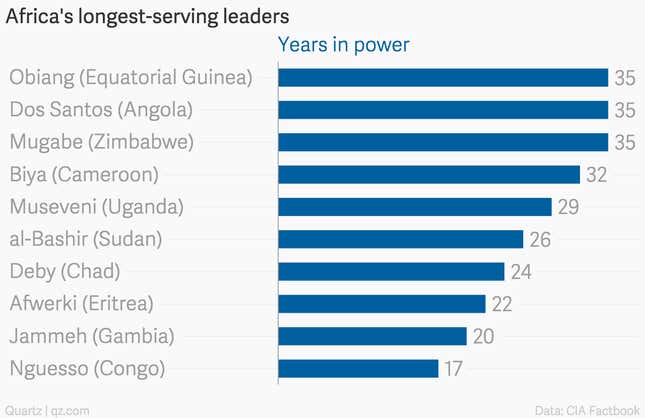

(Correction: This chart has been corrected to reflect full terms in power.)

Naturally, opinion is divided on this. There are those who argue that term limits rob a country of an experienced group of career politicians. Using term limits to force regular changes in government means that we lose the valuable experience that the old guard has acquired on the job. But the strongest argument often advanced is that term limits are unnecessary because if politicians are not doing a good job, nothing prevents them from being voted out of office. Voters can simply vote for someone else.

The problem with these arguments is that they miss the point of why term limits are necessary. It was Lord Acton—the English Catholic historian, politician and writer—who famously said that “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” The early pioneers of democracy always held the belief that people, when given power, will eventually be corrupted by it. Term limits are therefore not only desirable but are an essential part of the democratic enterprise because they ensure that candidates would have to leave office before corruption dominates their decisions.

Arguably African presidents are among the most powerful in the world. Here, what the president wants, the president gets. Just look at Rwanda—although the constitution allows only two terms, when president Paul Kagame wanted a third term in office all he had to do was ask. And now it’s almost guaranteed he will be a candidate in the next elections. Neighboring Burundi may be simmering with tensions over Nkurunziza’s bid for a third term in office, but that doesn’t faze him one bit. Why? Apparently his first term in office simply didn’t count. If even Mugabe finds this laughable, you get the sense of the how much power the average African president wields.

And that power doesn’t just stop with term limits. The president can fire anybody—from the vice president down to the lowly CEO of the state-run corporation—at will. In fact, the average African president is closer to a monarch than a president in any democratic sense of the word. As a general rule, the one thing you don’t want to do in Africa is to piss off the president.

So the necessity of term limits cannot be understated. However, the length of time it takes for power to corrupt a leader is an open-ended question and is at the heart of current debates on how long term limits should be.

Regardless of this, term limits are crucial because they serve another important function—leveling the electoral playing field. Incumbents always have an advantage over opposition candidates because they often have access to more campaign money, resources, and other privileges and perks by virtue of their incumbency. This heavily tips the scales of electoral victory in their favor. Without term limits, it would be very hard for an opposition candidate to come to power. This is especially true in African elections, where outcomes are heavily dependent on how much resources a candidate has rather than the policy proposals in his manifesto.

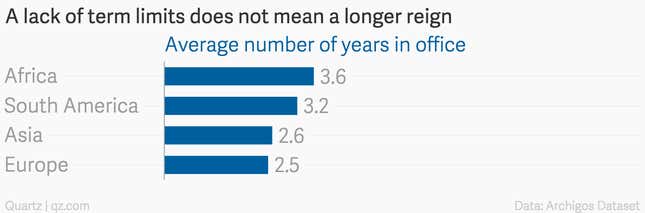

Mugabe is right that most countries in Europe are not particular about term limits but then again, incumbents there don’t last very long in office either. Part of that may be because many European countries have a parliamentary system of governance, where a vote of no confidence is all it takes to remove the incumbent. The presidential system practiced in many African countries means that no matter how disastrous a president turns out to be, he is not going anywhere until the next election rolls around. And that is if he is willing to go at all.

African elections are peculiar in the sense that the performance of the incumbent while in office often doesn’t play a big part in whether he gets reelected or not. When people vote along ethnic and tribal lines, you need term limits to ensure change. This is less of an issue in European elections, so in comparing Africa to Europe, president Mugabe may be comparing proverbial apples and oranges.

In the end, it all boils down to this—in elections where a powerful few have tight control and major influence over the fate of millions and millions of their fellow countrymen and women, term limits are simply non-negotiable.