Don’t overpay for an epic investing “FAIL”

Lowering the cost of actively managed funds is an important step in improving the odds of outperformance.

Summary

- Lowering the cost of actively managed funds is an important step in improving the odds of outperformance.

- Highly rated funds are not good predictors of future performance.

- Why a holistic approach with good judgment, including quantitative and qualitative elements is a “WIN!”

By Chris Philips, CFA

An investing “FAIL”?

Pop culture and investing rarely cross paths. After all, pop culture is hip, exciting, and flashy. Conversely, we’ve seen that successful investing is generally anything but. Nevertheless, the last decade or so has seen the rise of an internet meme that may be applicable to the investing world—“FAIL.”

So what are a “FAIL” and its illustrious cousin “epic FAIL”? Both are generally used to describe embarrassing events, such as setting your kitchen on fire as you film yourself attempting to light birthday candles (FAIL)—by using a blowtorch to be cool (epic FAIL).

Now I hope none of us have burned down a house while reviewing an investment portfolio! So I can’t visualize an investing epic FAIL in this vein (although some may suggest that the global financial crisis would suffice), but there are at least three areas where I can confidently say FAIL: cost, ratings, and performance.

The cost-value riddle

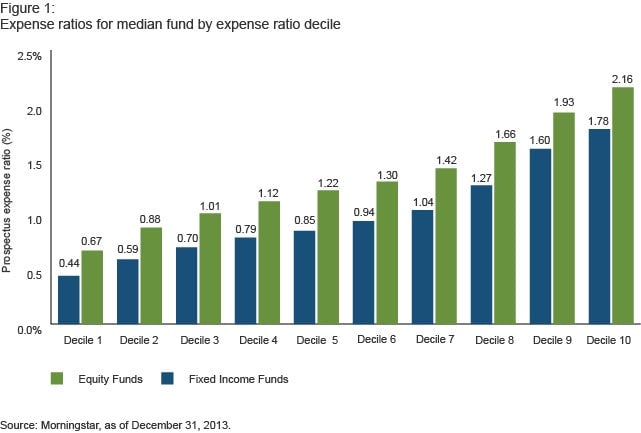

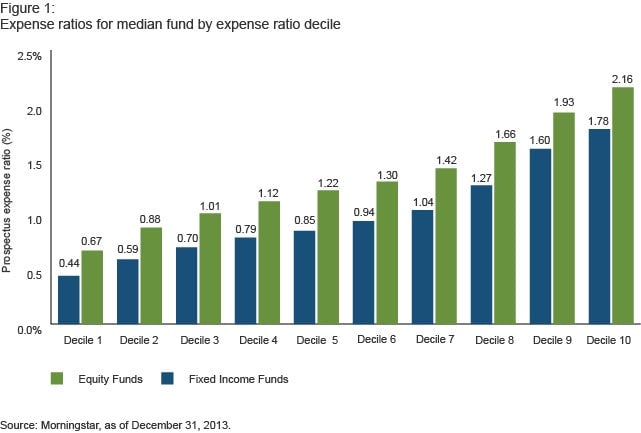

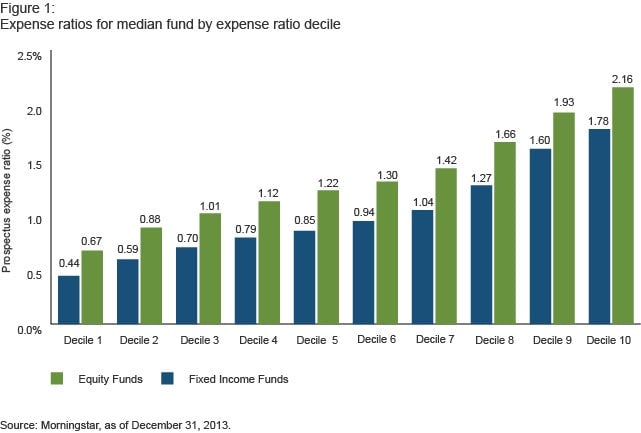

First up is the issue of cost. People intuitively associate higher cost with value and performance. Unfortunately, it’s backwards. For example, see Figure 1, where I break out U.S. equity and fixed income funds into deciles according to their reported expense ratios. Cost and performance ARE related. However, the data show that the lower the cost, the better the experience (on average).

You should pay more for performance? FAIL

Relying on ratings

Next is the question of industry ratings. The allure of something—anything—that could potentially help us do better by our clients is strong.

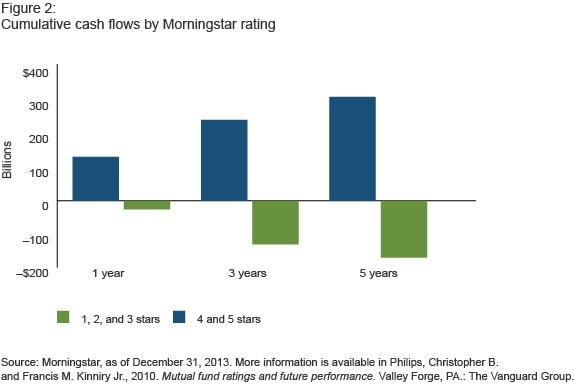

Figure 2 illustrates this—investors have clearly favored higher-rated funds and shunned lower-rated funds. These patterns wouldn’t be noteworthy if 4- and 5-star-rated funds consistently added value. (Or perhaps they would be, if they revealed a metric that could reliably predict performance!)

However, in the research underlying Figure 2, we showed that highly rated funds in one rating period tended to be the worst performers relative to a style benchmark over the next 3 years—underperforming on average by 138 basis points per year. Funds with 1-star ratings also underperformed, but at a much more modest rate of 15 basis points per year.

You should stick to top-rated funds? FAIL

Patience and performance

Of course, some may dismiss the cash-flow example as “retail” investors chasing returns. However, there’s also evidence of return-chasing among institutional investors.¹ After all, we are all human, whether acting in a fiduciary capacity or on our own behalf.

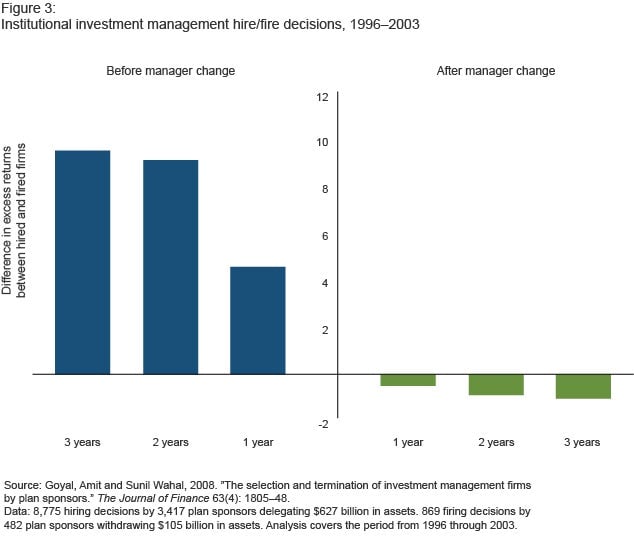

In an article published in The Journal of Finance, Amit Goyal and Sunil Wahal reported on the outcomes of hire/fire decisions across a broad sample of plan sponsors. They found that underperforming managers were (not surprisingly) replaced with managers who demonstrated significant outperformance (represented with blue bars in Figure 3). I say “not surprisingly,” because what fiduciary would want to keep an underperforming fund or asset on the books?

However the twist is in what happened following the replacement. On average, those managers who were hired to replace the poor performers underperformed the same managers they replaced in the next 1-, 2-, and 3-year periods! In Figure 3, this record is shown by the green bars.

You should systematically replace underperformers? FAIL

Avoiding FAIL

The moral of this story is that while ratings and cost should not be summarily dismissed, we should take a collective step back and think about what really matters when constructing portfolios or looking to provide clients with the best opportunity for success.

Controlling costs is critical, to be sure. But equally important is a robust evaluation process that includes many variables for considering whether fund A, B, or C should be added, dropped, or ignored. Such a qualitative process can complement the quantitative metrics that have been shown to potentially lead us astray.

A holistic approach with good judgment, including quantitative and qualitative elements? Now that’s a WIN!

This article was produced by Vanguard and not by the Quartz editorial staff.

_______________________________________________

¹Mark Grinblatt, Sheridan Titman, and Russ Wermers initiated the academic literature on return-chasing behavior among institutional investors in their paper “Momentum investment strategies, portfolio performance, and herding: A study of mutual fund behavior,” The American Economic Review, 85(5), 1995.

Notes:

- All investing is subject to risk, including the possible loss of the money you invest.

- Past performance does not guarantee future results.