Americans really do have to work harder to stay middle class

Few ideals are as universally celebrated in the US as the “middle class.”

Few ideals are as universally celebrated in the US as the “middle class.”

Both Republican and Democrats claim to represent the interests of this somewhat poorly defined group. And it’s no wonder.

Roughly 90% of Americans describe themselves as “middle class”—either, upper middle class, lower middle class, or plain middle class—according to recent research from the Pew Research Center. That’s a highly desirable bloc of potential voters.

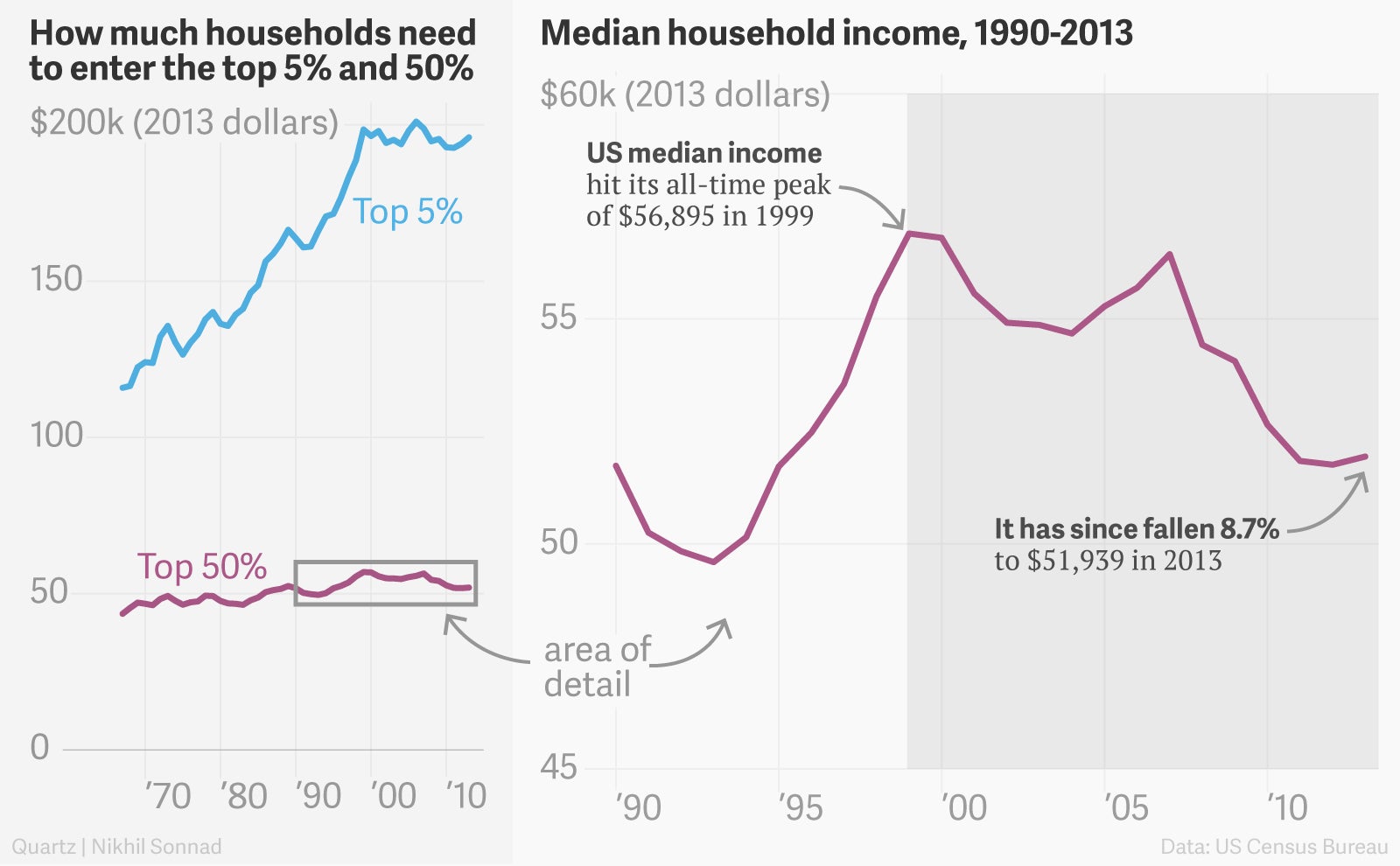

And they’re a group that’s stuck in a rut, making them especially insecure. US real median household income—the dead center of the US income distribution that’s typically seen as a good proxy for the middle class household—in 2013, the most recent year available, was the same level as roughly 25 years ago.

In fact, real income of the median American household is about 1% below where it was in 1989. And median household income is 9% below the all-time peak of $56,895 in 1999. (Incomes are also 8% below their recent high water mark in 2007, when they hit $56,436.)

Some believe the situation is even worse. Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis recently published a study showing that if you define the middle class based on traditional characteristics of such families, middle class livings standards have gone into an outright decline.

Analysts at the bank took survey data and broke respondents up into buckets based on demographic criteria such as race, age, and education level, rather than income. They defined “middle class” families as “headed by someone at least 40 years old who is white or Asian with exactly a high school diploma or black or Hispanic with a two- or four-year college degree.”

Then they looked at how the income and wealth of families that met those criteria developed over time in the Fed’s surveys, which are conducted every three years.

The upshot: Instead of being flat, real median income of these “demographically defined middle-class” households fell roughly 16% to $45,248 in 2013, from nearly $54,000 in 1989.

Basically, this confirms what many people know from experience: If you want to stay in the US middle class, you’ve got to clear higher hurdles than previous generations.

“If you are a high school graduate and your parents were high school graduates, it’s likely that you are less well off than your parents,” said William Emmons, a St. Louis Fed economist, who co-authored the study.

Emmons said the findings of the Fed study are consistent with other theories on shifts in the structure of the US labor market. MIT economist David Autour has argued that in recent decades the US job market has become increasingly hollowed out. There have been opportunities in very high and low-end employment. But at the same time, middle-skill, middle-wage occupations such as clerical, administrative and production jobs have declined amid rising automation and other technological developments.

“I think these numbers are consistent with that story,” Emmons said of the “hollowing-out” narrative.