Indian prime minister Narendra Modi has decided to use his clout on social media to try and fix one of the most intractable problems in the country today—the declining male-to-female ratio.

On June 28, Modi launched #SelfieWithDaughter on Twitter. The campaign’s aim is to spread awareness about gender imbalance and urge parents to value their daughters. Within hours, Twitter was flooded with parent-daughter selfies, shared along with #SelfieWithDaughter.

In many parts of India, daughters are considered to be a burden because of the dowries required to marry them off. Parents also tend to view a son as a means of lifelong support, unlike a daughter who becomes a part of her husband’s family after marriage.

The result of these beliefs is that India’s child sex-ratio (below six years) is now the worst in 70 years, with 918 girls per 1000 boys in 2011. If the ratio does not improve, it could lead to a deficit of 23 million women in the age group of 20-49 years by 2040.

This discrimination isn’t just limited to India’s uneducated or low-income families. A 2011 study by the Centre for Global Health Research—a non-profit which works on health issues—found that selective abortion of girls is more common in wealthy households, and among women with at least a decade of education.

In spite of these grim statistics, there are still men and women in India who have only one child—a daughter—and choose to stop there.

I am one of those daughters.

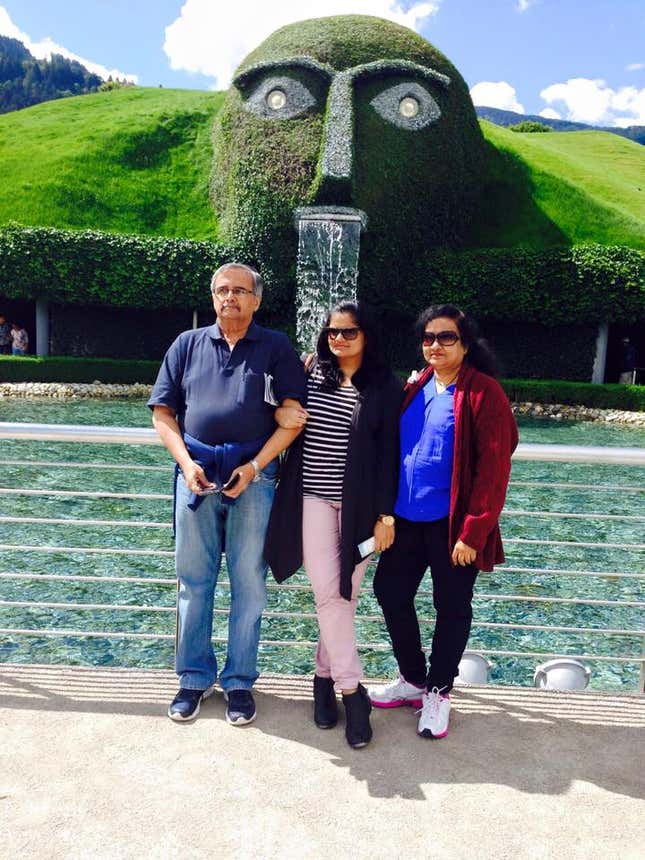

My parents had me 27 years ago and I am the only child. I spoke to them to find out more about this choice, which wasn’t an easy one to make. Here is what they had to say:

Sunil Karnik, 59, businessman

Everyone is talking about Modi’s #SelfieWithDaughter campaign. It is a welcome change that at least there is talk about the girl child. The campaign may try to create that awareness, but the mentality needs to change.

For instance, as a businessman and the father of an only daughter, there is one thing I have heard many times: “Oh you don’t have a son? Who will then look after your business?”

I laugh at them and this is my standard response: What if my son wasn’t interested in my business—and why can’t my daughter look after it? It is a different issue that she may have her choices too. But she isn’t incapable of handling it.

When I and my wife decided not to have any more children, after my daughter was born, I was apprehensive at first. Not because I wanted a son, but because growing up with a sibling is a good experience. I grew up with two brothers. But we took the decision and I don’t regret it.

I never worried about the future, and still don’t. I am capable of taking care of myself. Financially, I am stable enough to support myself and my wife. Even if I wasn’t, I know I could count on my daughter. And I would not have planned my retirement any different if I had a son. I would have been as independent.

Gender does not matter here. It is the person. It is the upbringing and values.

Still, Indians are obsessed with sons. There is one question we should all ask: If we want a mother, a wife, and a sister, then why not a daughter? Why the hypocrisy?

The society’s approach that a daughter can’t look after her parents post-marriage needs to change. A daughter is responsible for her parents as much as a son is. And there is nothing wrong for parents to expect that from her.

I will not shy away from asking for monetary help from my daughter. It is time we stop discriminating between our sons and daughters.

Seema Karnik, 54, housewife

I grew up in a middle-class family along with three elder sisters. My parents were employed—my father with the government and my mother as a school principal—and never once did I feel the need of a brother, or a male in the household, who would take care of my parents after all of us were married. My sisters and I were capable of doing that.

And that is perhaps why I never wanted a son.

When I was expecting my child, I was desperately hoping that it wouldn’t be a son. I had always wanted a daughter. I think daughters are equally capable—sometimes even more—of taking care of their parents.

When my daughter was born, I instantly decided I would not have any more children. A lot of relatives and friends did not approve of my choice and asked me to have a son who could take care of me when I became old.

Frankly, I didn’t even think about the future then. I always ended up telling them that my daughter will be enough to take care of us.

In fact, we are well prepared to take care of ourselves. And this is something people need to realise. Having a son would not guarantee lifelong support—both emotionally and financially. There are plenty of cases to prove that.

My daughter may get married within a couple of years, and this is when friends tell me there may be “problems.” People say some families might have an issue with marrying their son to an only child as this would mean the daughter would be responsible for her parents lifelong. To these people I say, I don’t want such a family for my daughter anyway. To be fair, the same principle could be applied to an only son. Do parents think about this when they marry off their daughters to a family with an only son?

So many of my educated friends had a second or third child because they wanted a son. Some were disappointed that they could not have one. Many educated Indians abort the girl child. I really pity the intelligence of these people.

A daughter completes my family.