These guys protested the Confederate flag 20 years ago and all they got was this defunct t-shirt company

In 1994, long before South Carolina’s long-awaited decision this week to remove the Confederate flag from a prominent place adjacent to the statehouse, where it had been since 1961, Sherman Evans and Angel Quintero made the trip from Charleston to Columbia to demand just that.

In 1994, long before South Carolina’s long-awaited decision this week to remove the Confederate flag from a prominent place adjacent to the statehouse, where it had been since 1961, Sherman Evans and Angel Quintero made the trip from Charleston to Columbia to demand just that.

In an act of protest and self-promotion, they insisted a flag of their own design be hoisted in its place. Theirs was the Confederate flag redone in the red, black, and green of Marcus Garvey’s pan-African flag—which also happened to be the logo for their clothing company, NuSouth.

Before a Confederate battle flag-loving Dylann Roof allegedly killed nine black churchgoers in Charleston and forced a national conversation over it, before Kanye West was throwing it on his tour merchandise and Andre 3000 was sporting it on belt buckles in his music videos, NuSouth’s creators were trying to reclaim the Confederate flag as a symbol for black Southerners—and make a little money to in the process.

Reason’s Jesse Walker, who wrote about NuSouth in 1999, recently drew a rough parallel between its appropriation of the flag to that of the Southern Student Organizing Committee, a student activist group that tried to reclaim it for their anti-racist work. And in an essay for Politico Magazine, Issac Bailey recalled NuSouth as a stand-in for black Southerners who “have been swinging in their own way for years” on the symbol.

“We always thought the Confederate flag had nothing to do with us,” Evans told Quartz. “But in truth it has everything to do with us.”

The company would eventually fold in 2001, but by then it had managed to secure a space in some Southern memories, where it still complicates notions of the region’s relationship with the rebel banner.

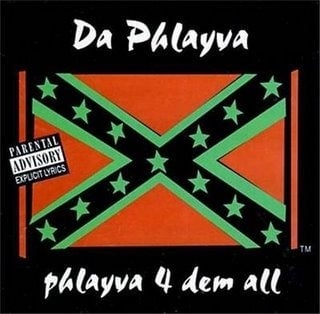

The design was originally album art for Da Phlayva, a Charleston hip-hop group signed to Quintero’s record label. When they debuted in 1993, acts like Outkast and Three Six Mafia had yet to secure the South’s place in rap canon, so they needed a way to stand out.

“We just came to a point where we said, ‘what’s the biggest symbol representing the South?’” Quintero told Quartz. “The Confederate battle flag,”

Quintero recruited local artist Colin Quashie to help design the graphics. At the time, he’d been working on a series of six Confederate flags in the pan-African colors, entitled “Options,” and that’s what they went with.

“Everyone was shouting it’s about heritage not hate and these guys said ‘fine,'” said Quashie, who falls decidedly in the “hate” camp. (“It was put up as a symbol of intimidation for African-Americans during the civil rights movement,” he told Quartz. “That’s all it will ever be.”)

When Quintero & co. printed up a run of shirts to toss out at Da Phlayva shows, local black high-schooler Shellmira Green managed to grabbed one. She promptly wore it to school as a rebuttal to white classmates wearing shirts with slogans like “100 percent cotton and you picked it.”

When they complained to the principal, he forbade Green’s shirt on penalty of suspension. She wore it anyway and was sure enough suspended. The story went national (paywall) after the local NAACP chapter filed a lawsuit to support her.

“I wanted to wear the t-shirt to school because it stands for black people of the South—white people aren’t the only people living in the South. That’s why I liked it.” Green told reporters at the time (paywall).

The suit would eventually get dismissed, but Quintero and Evans, who was co-executive producer on the album, quickly saw that the controversy was good marketing.

“All of a sudden, we started printing more and more shirts, more and more apparel around it,” Evans said. “There was no getting around it. You had to talk about it.”

The music would eventually take a back seat to the clothes. NuSouth, born soon thereafter, started directly speaking (and selling) to the Shellmiras of the world—their ads hinted at a new Southern unity, including taglines like “For the sons and daughters of former slaves, and for the sons and daughters of former slave-owners.”

They used protests of their own making to keep the buzz going. Before their rainy 1994 day in Columbia, they sent out press releases to local news outlets and handed them out in the city’s black neighborhoods. But because they only printed them in black and white, the message behind the NuSouth flag didn’t go across as intended. “One lady said ‘I’m not coming out to that. That’s the klan,” Sherman said.

She wasn’t the only person put off by the brand. Quintero said most of their early sales were actually to white customers. Black Charlestonians might have been understandably hesitant to wear any version of the flag in the birthplace of the Confederacy.

Despite the buzz, the brand never really caught on, even after a 1997 GQ profile. Whereas early ’90s mainstay Cross Colours had reportedly booked $100 million in sales, NuSouth never broke more than six figures.

And though the brand made it into a few boutiques across the US, its controversial nature made it hard for Quintero and Evans to land big national retail contracts. Investors were similarly hard to find. (Ironically, one of the only interested backers was William Dorris, a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the man behind a local shrine to early Ku Klux Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest. “I thought they had a damn good idea,” Dorris told Quartz. “They were going after the black merchandise market.”)

Seven years after they started, they were finished.

After closing up shop, the pair went back to their lives, Quintero to his auto detailing business and Evans to his clothing store downtown. A few months ago, before Roof’s alleged attack, they said they started shooting a documentary to tell the NuSouth story.

They said the film should be out by next summer, and they’ll gauge its reception before deciding whether they’ll bring the brand back.

“The support is there way more than it was then, because people get it now,” Quintero said.

Evans, who thinks NuSouth would have been much bigger if the Confederate flag had come down sooner (“We’d be so much further ahead in the healing that needs to take place.”) is a bit more ambivalent on the role of a t-shirt company in the debate over powerful symbols.

“Maybe social change isn’t supposed to be profitable,” he said. “Maybe the flag shouldn’t be on a shirt.”

Both men think it should have come down years earlier, though they expressed sadness over the circumstances that led to its removal.

“Look what we had to lose to gain that,” Quintero said. “By now, we’re connecting it to nine people who had to lose their lives to change it, and we could have done it so long ago.”