Massacre in Algeria: In hostage situations, the leverage is almost always with the captors

The history of rescue-missions-gone-wrong–Munich, Tehran, Nord-Ost, Beslan, and today in Algeria–demonstrates why they are one of the hardest operations that special teams carry out. The trouble is the moving parts, experts say–the layout and location of the place they are being held; the mood, experience, objective and weapons of the kidnappers; and the number, mood and condition of the hostages.

The history of rescue-missions-gone-wrong–Munich, Tehran, Nord-Ost, Beslan, and today in Algeria–demonstrates why they are one of the hardest operations that special teams carry out. The trouble is the moving parts, experts say–the layout and location of the place they are being held; the mood, experience, objective and weapons of the kidnappers; and the number, mood and condition of the hostages.

There of course are legendary cases of success, most prominently the 1976 Mossad raid in Entebbe that rescued 105 Israeli hostages.

But almost always, the leverage seems to be on the side of the captors. “The wild card is that you can never train for how the kidnappers will react. That is what makes it so difficult,” said Rick Nelson, a former US Navy intelligence officer who advises the Center for Strategic and International Studies and teaches at Georgetown University. “A decision to rescue is inherently high-risk.”

Here are some examples:

• At the 1972 Munich Olympics, a Palestinian group called Black September took 11 members of the Israeli team hostage, all of whom were killed. The German rescue operation is a prime example of a fast-moving, fast-changing situation that turned into tragic fiasco.

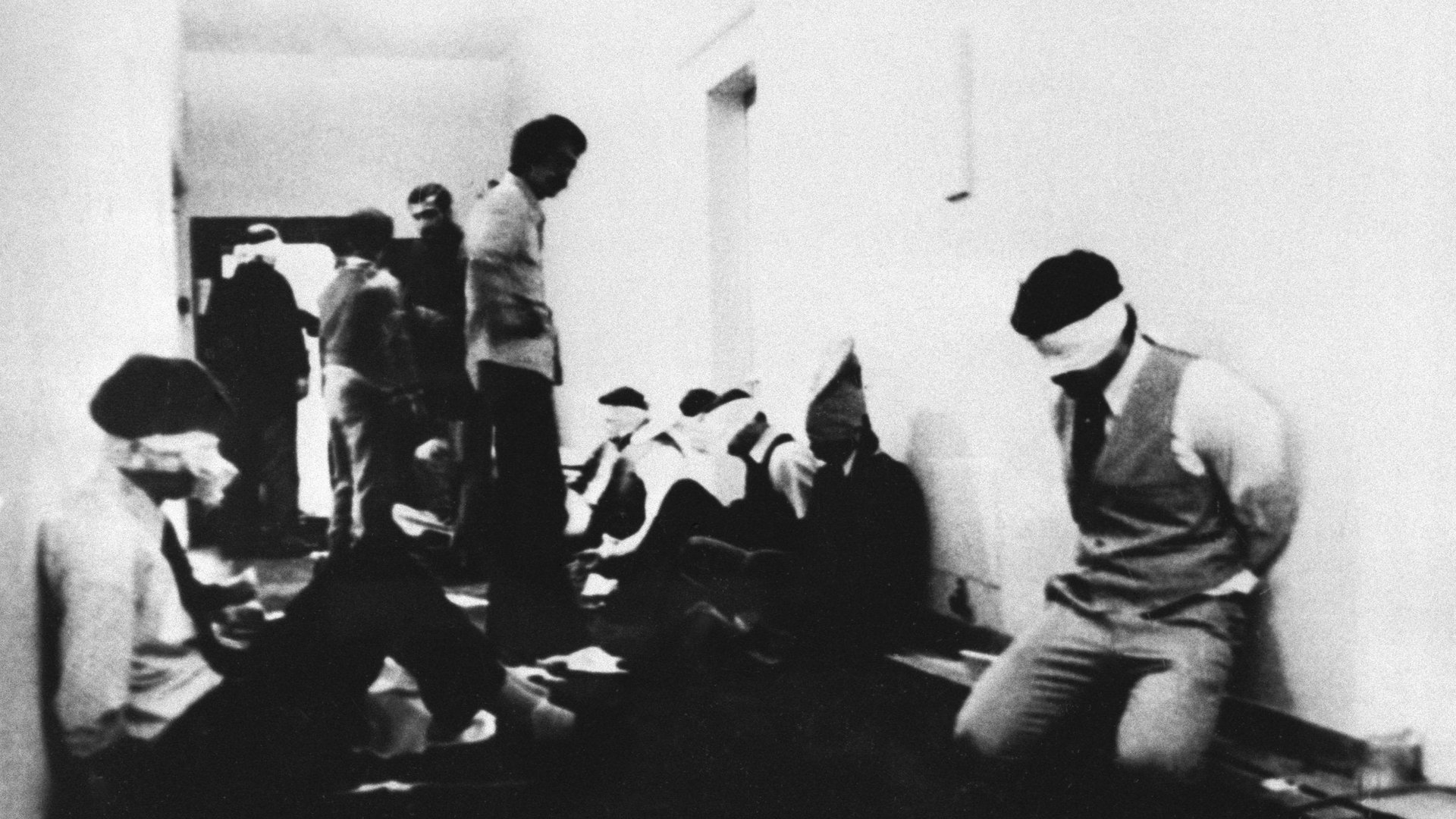

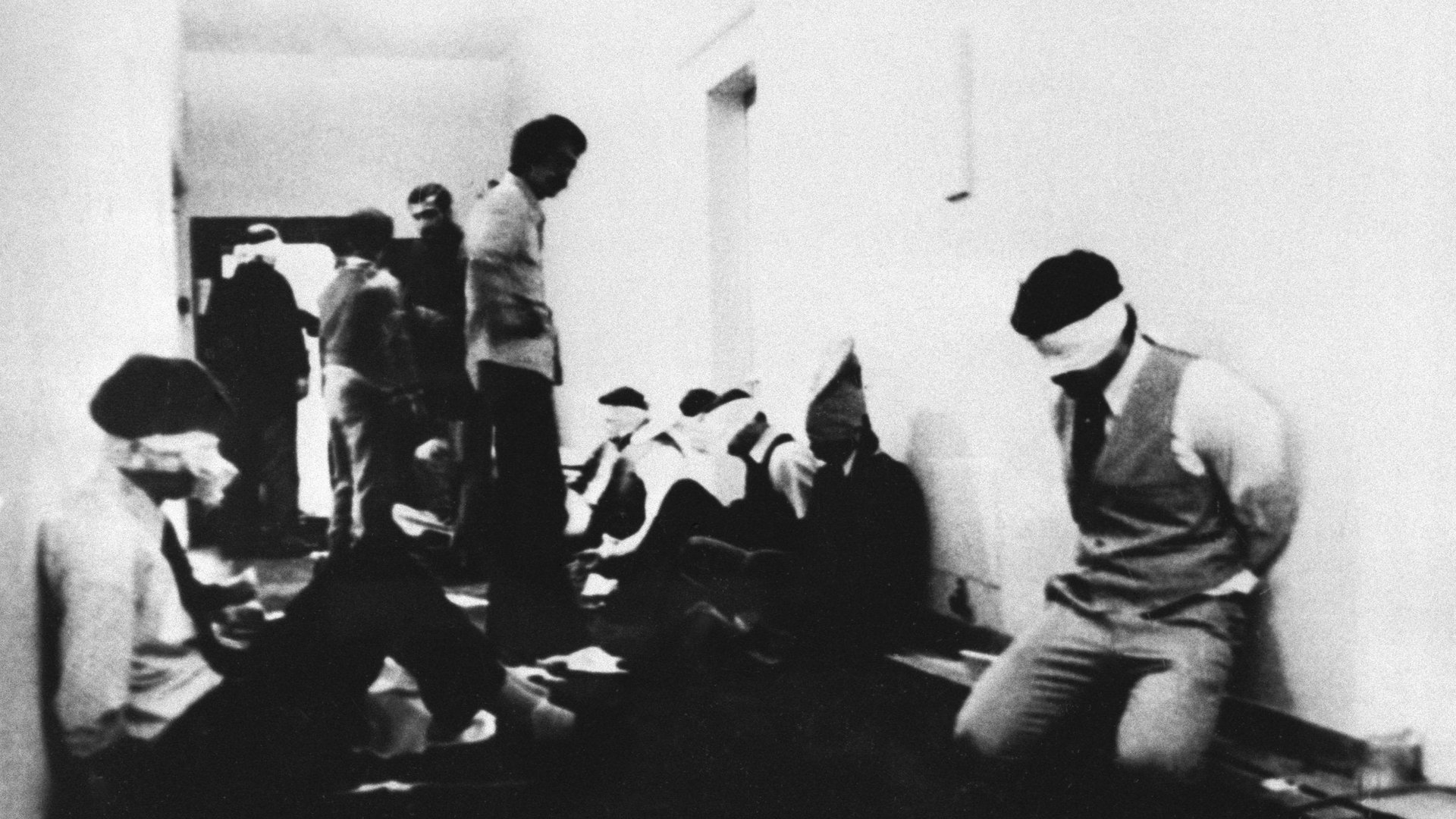

• In the 1979 Iranian hostage crisis, 51 Americans were held captive for 444 days before being released moments after the inauguration of Ronald Reagan as US president. Along the way, eight US soldiers were killed in a rescue operation when a gigantic storm engulfed their aircraft, dooming the operation and stigmatizing President Jimmy Carter as a weak leader.

• In 2002, Chechen militants stormed into a Moscow theater playing the musical “Nord-Ost,” and took 850 people hostage. On the third day, Russian forces pumped an opiated gas into the theater, and stormed it. They killed all 39 captors; 129 of the hostages died, almost all of them because of the gas.

• In 2004, militants took over a school in Beslan, in southern Russia, where they held 1,200 children, teachers and family members. On the third day an explosive booby-trap that the attackers had rigged up went off by accident, prompting troops surrounding the school to start firing; in the ensuing chaos, 331 hostages and soldiers died, as well as all 31 hostage-takers.

In Algeria, militants took 41 foreigners hostage early Jan. 16 at a natural gas field run by Norway’s Statoil. Reports at the moment are that as many as 35 may be dead after the captors attempted to move them by vehicle, and Algerian forces opened fire.

But Chris Voss, a former FBI kidnapping negotiator who runs a firm called Black Swan Group, told me that the circumstances of the kidnapping made a rescue operation very difficult. “The probability of a successful rescue [was] very low,” he said.

Mark Galeotti, a professor at New York University, said that people simply have an inaccurate image of hostage situations–“the myth of the surgical strike,” in which special forces wearing black masks swoop in and rescue victims “like in the movies.” “It can become a real disaster,” Galeotti told me. “[Algeria] is a classic example.”

It is not that the Algerians are not set up for such operations. Since the mid-1990s, they have had French-trained special forces known as the GIS. But they are action-driven, and typically do not include negotiators, who are the front line of western hostage situations, Galeotti said. In successful rescue operations, you want to go as far as you can using negotiators. “Good operators realize that in a complex environment, the high-adrenaline rescue mission is rarely the best option,” he said. “It is the last, worse case.”

In Algeria, the kidnappers’ objective in taking the hostages remains murky. While spokesmen used grand terms of a reprisal against the West because of operations in Mali against Islamist militants, the captors’ leader—Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who may have been killed in the operation—is notorious for high-ransom kidnappings and cigarette smuggling (his nickname is Mr. Marlboro.). In 2009, Germany and Switzerland paid his group $8 million for the release of four Westerners including two Canadian diplomats.

This suggests that the kidnappers might have been prepared to bargain for the captives’ release. But Galeotti is doubtful that the captors would have been swayed by money. “When you entrench yourself, you are making a statement,” he said. “Jihadists would not have wasted the situation.”