Apple’s App Store could take a lesson from Apple Music on the human touch

The limitations of algorithmic curation of news and culture has prompted a return to the use of actual humans to select, edit, and explain. Who knows, this might spread to another less traditional media: apps.

The limitations of algorithmic curation of news and culture has prompted a return to the use of actual humans to select, edit, and explain. Who knows, this might spread to another less traditional media: apps.

When San Francisco’s de Young museum prepared its David Hockney exhibition a couple years ago, it didn’t just randomly slap works on its walls, leaving visitors to guess at the stories behind the offerings. A group of curators (from the Latin taking care) decided which of the artist’s “monumental paintings, Photoshop portraits, digital films that track the changing seasons, vivid landscapes created using the iPad, as well as never-before-exhibited charcoal drawings and paintings completed in 2013 ” to show, in what order and grouping. And they added the all-important museography, words that introduced the show and explained each work, its origin, story, place in the context, with occasional comments about technique or aesthetic sensibility.

Without these knowledgable and trustworthy curators (Hockney among them), the exhibition would have been far less pleasurable, it would have lacked a connection to the artist and his world.

Another type of curator, one whose role as trustee is even more crucial, is a newspaper’s editor-in-chief. Simplifying a bit, this individual is responsible for the mix of news articles, opinion columns, special sections such as food and travels, in-depth analytical articles or investigative series. When we read—and pay for—the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal, we enter into an agreement: We trust the Editor-in-chief to provide a satisfying assortment of articles, some expected, others less so, but not so wildly that they don’t fit the newspaper’s established formula and voice. When the Times danced a little too craftily around “the T-word”, readers saw this as a breach of trust, a breach that could hurt the newspaper’s numbers.

With search engines, we see a different kind of curator: algorithms. Indefatigable, capable of sifting through literally unimaginable amounts of data, algorithms have been proffered as an inexpensive, comprehensive, and impartial way to curate news, music, video—essentially everything.

The inexpensive part has proved to be accurate; comprehensive and impartial less so. No matter what their proponents (and sellers) say, algorithms aren’t intelligent. They’re dressed up in rich-sounding names and euphemisms such as “Machine Learning”, or oxymorons such as “Affective Computing”, but however they’re decorated, algorithms don’t understand meaning.

Certainly, algorithms can be built to perform specialized feats of intelligence such as beating a world-class chess player or winning at Jeopardy. Like many, I have personal reasons to hope for the continued development of algorithms that sift through huge amounts of information (a.k.a. Big Data) to pave the road to cures for DNA anomalies. And on an even more selfish note, the business of algorithms—the tech world—has fed me and my family quite well for the last half century.

But ask a computer scientist for the meaning of meaning, for an algorithm that can extract the meaning of a sentence and you will either elicit a blank look, or an obfuscating discourse that, in fact, boils down to a set of rules, of heuristics, that yield an acceptable approximation. As times goes by, the rule book gets thicker, but meaning remains elusive. Google Translate, an algorithm that many consider to be the most prominent Machine Learning engine on the planet, stumbles on a simple sentence such as “les poules couvent au couvent” (“hens hatch in the convent”), tripped up by a grade school word equivalence:

(The translation engine can’t even translate “les poules couvent” —“the hens hatch”. It mistakenly renders it as “the convent hens”.)

The belief in algorithmic power to make sense of meaning spreads wide (and rich). At a recent meeting with a visiting French journalist and digital media expert, a venture investor explained how a news aggregator algorithm transforms a story into a list of points, making it much easier for “content consumers” to digest (and for advertisers to place ads). I wonder about running the Iliad, The Taming of the Shrew or Arthur Rimbaud poems thru this listicle machine…

Trust in algorithms is damaged when a prominent search engine is accused of putting its thumb on the scale and might get into real trouble with European authorities for unfair practices. Tomes have been written on the role of trust in prosperity. We need to trust that our person, our property, the fruit of our labors will are safe from the claws of private or public mafias. Our trust that others will respect the rules of the road, literally and figuratively, is what makes civilized life civil. One only has to look at places where this isn’t the case to appreciate the worth of public and private faith in others’ behavior.

But should we be shocked when we hear that search algorithms aren’t fair and balanced? Algorithms are designed and built by humans and they reflect the biases of their makers. To paraphrase an old adage, It’s Humans All The Way Down. Humans are born with the gift of guessing, of divining the rules of the game—that’s how we learn speech. This Gift From The Genes allows us to smell manipulation behind the pretense of impartiality, hence the disenchantment and possible legal actions when we find that the sanctimonious representations of fairness are clumsy fig leaves covering human shenanigans.

As the limitations and misrepresentations of algorithmic curation become more obvious, the marketplace turns back to humans. As Business Insider’s analysis of the Apple Music announcement put it:

“Most online music services rely on computer programs to recommend songs and build playlists. But Apple is placing a big bet on human editors with a strong knowledge and love of music. The idea is that these human editors, like the radio DJs of yesteryear, will help turn Apple Music into a great way to discover new music.”

It’s too early to judge the success of the new Music service, I’ll need a while to get to my Third Impression, to see how the novelty wears off, or how the confusion clears up. But I’m encouraged to see a more human touch openly applied to the curation of an art form.

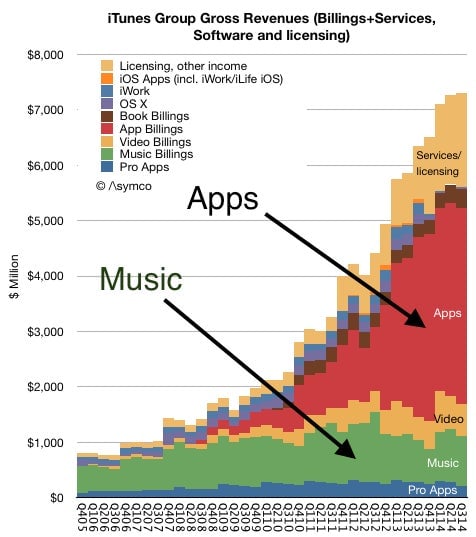

With this in mind, let’s look at one of Horace Dediu’s graphs from earlier this year where he shows apps to be Bigger than Hollywood:

For a while now, music downloads have paled when compared to apps–hence Apple’s move to a streaming service. But there’s another idea lurking in there: If it’s a good idea to use human curators to navigate 30 million “songs”, how about applying human curation to help the customer find his or her way through the 1.5M apps in the Apple App Store? Apple bought Beats for $3B and spent a good chunk more to build its Music product. Why not take another look at the App Store jungle and make customers and developers even happier?

To be sure, Apple has had to apply a special effort to its music service in order to catch up with established streaming competitors such as Spotify, Pandora, and others. But being in the lead in the App Store category shouldn’t breed complacency and prevent the company from seizing opportunities for better human curation. The recent iPad mini-site is a well-executed step in this direction. We hope the editor-in-chief will give us more.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.