Why China is on the brink of its very own subprime crisis

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, just okayed 3 trillion yuan ($482.6 billion) in new lending for 2013. It’s not much more than what it allowed in 2012—but still a considerable sum for a country struggling with overcapacity.

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, just okayed 3 trillion yuan ($482.6 billion) in new lending for 2013. It’s not much more than what it allowed in 2012—but still a considerable sum for a country struggling with overcapacity.

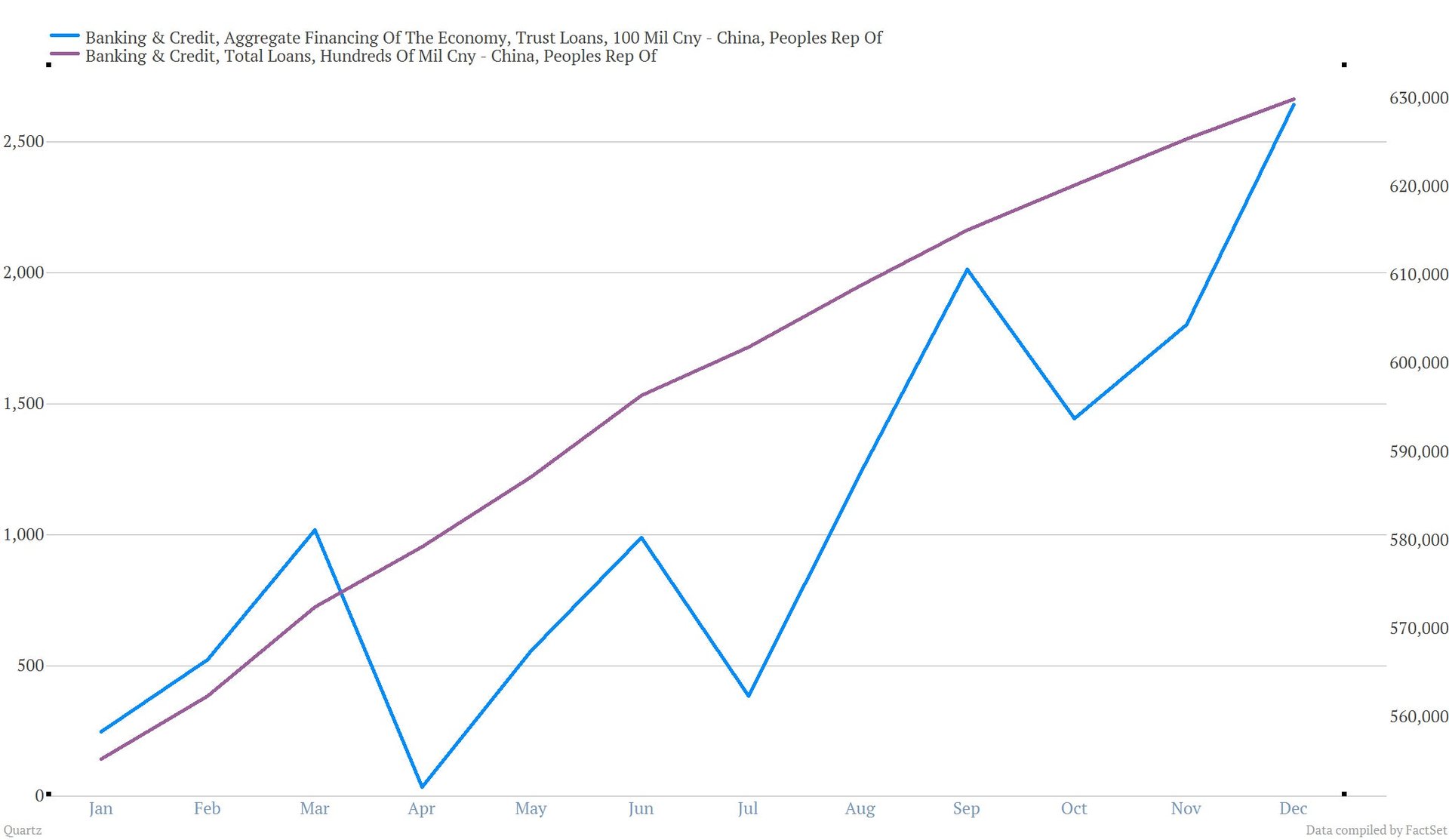

That’s merely worrisome though. What is actually stomach-churning, though, is the 679% year-on-year increase in “trust loans” disbursed in December, hitting 264 billion yuan. And, yes, that’s 679%, not a typo. (We recently explained in detail why these super-shady investment vehicles—which allow banks to finance off-the-books loans to companies and local governments by offering them to their retail customers as investments—should unnerve everyone, but the key words here are “Ponzi” and “scheme.”) The central bank also noted today that it expects a 16% year-on-year increase in “total social financing,” a hefty portion of which is trust loans.

“Short-term financing instruments such as trust loans have been rising really quickly,” Zhang Zhiwei, chief China economist at Nomura, told Bloomberg. “Quite a number of companies resort to trust loans when they face financing troubles. A breakdown in this financing chain will eventually lead to a default on debt this year.”

But there’s no equivalent of America’s Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to swoop in if that happens. The high-profile default of a 160-million-yuan trust savings vehicle resulted in precisely nothing clear, though the bank is supposedly going to work out a repayment scheme with swindled investors. That means there’s no protection against a bank run (a very mini one already happened this summer, in the collapse of a Ponzi scheme).

But back to the on-the-books loan for a moment. Economist Patrick Chovanec gives the context on the quality of investment that will be funded by that 3 trillion yuan:

Existing loans… are of minor concern compared to new ones. China’s banks are approving loans not because the business climate is promising or because proper credit analysis indicates they can profit by doing so, but because the government has told them to let the money flow. And the figures in financial statements suggest that the banks are making inadequate provision, in terms of increased reserves or the like, for any of these “loans” going bad.

What’s perhaps a little more telling about this whole situation is that paragraph is still entirely relevant—even though Chovanec wrote it back in May 2009. If it was the case back then, what can these loans possibly be funding right now?