We now have an economic theory that explains the reckless rock ‘n roll lifestyle

Neil Young was right. It is sometimes better to burn out than to fade away.

Neil Young was right. It is sometimes better to burn out than to fade away.

This is what economic theorists have found, too, and it helps explain something that’s bedeviled them for generations: Irrational agents. In economics, these are people who consistently behave in a way that is at odds with what might be called the “correct way.”

In the decades leading up to the financial crisis, most bankers, economists, policymakers, and politicians subscribed to the idea that people are rational beings, constantly evaluating costs and benefits and choosing options that maximized their own utility. (Utility, in econospeak, equates roughly to “happiness.”)

This school of thought—central to the neoclassical economics revived by Milton Friedman—teaches that irrational agents will eventually be driven out of existence. They will either change their behavior or be overrun by more rational players.

In other words, neoclassical economists “don’t have to worry about irrationality, because irrationality does not survive,” says Elyès Jouini, whose new paper, entitled “Live Fast, Die Young,” was recently published in the Journal of Economic Theory.

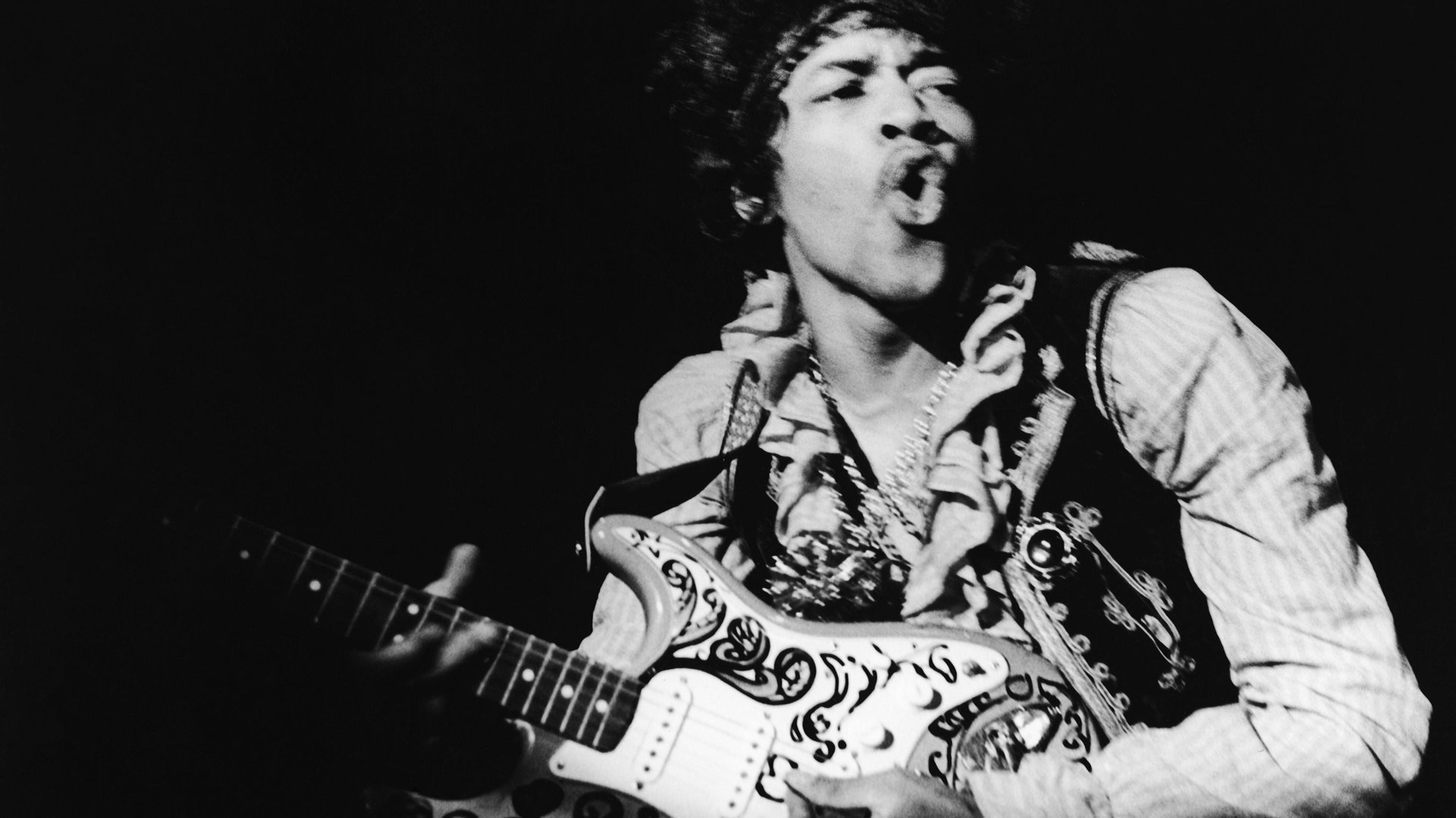

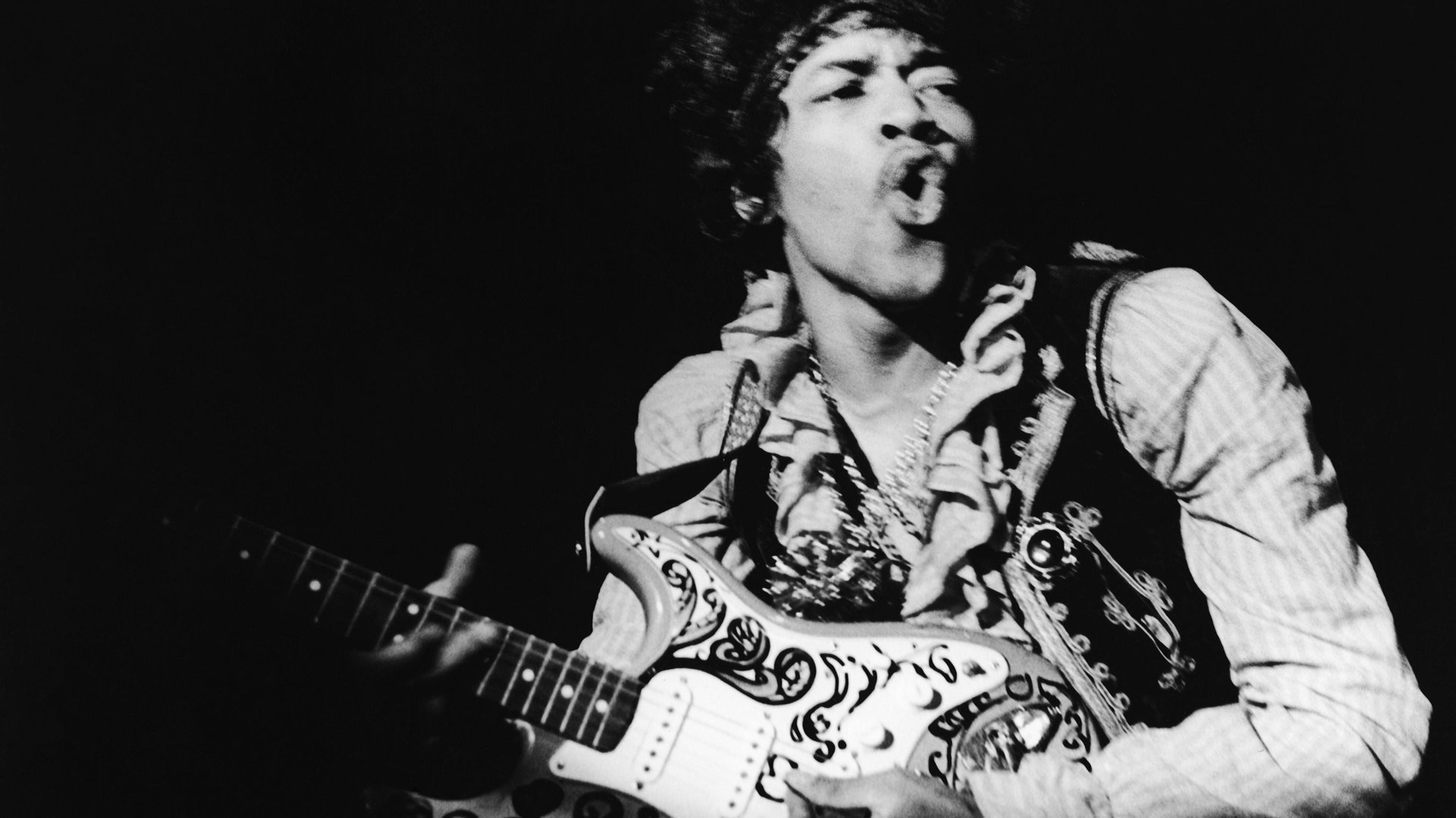

Now look around. You’re likely to see plenty of people who behave in ways that are inherently irrational. Smokers, drinkers, nutty drivers, lottery-ticket buyers, and yes, rock ‘n roll stars. They take irrational risks with their health, their money, their relationships—and yet they have not been driven out of the world altogether.

It is in large part thanks to these people that we now have the field of behavioral economics, which was developed to explain the persistence of such creatures. Building on psychology, economists such as Richard Thaler set about cataloging the myriad ways that actual human behavior differs from the behavior predicted by the neoclassical models. Real people take mental shortcuts. They lack self-discipline. They rely on defaults. They’re not great at math.

While behavioral economics can be terrific at explaining the existence of idiosyncratic economic decisions, critics point out that it lacks the all-encompassing theoretical background of neoclassical economics.

Jouini’s paper attempts to bridge that gap. Making just a few modifications to standard economic models allows you to come up with results that look at lot more like the reality that behavioral economics has done such a good job of describing, he says. One key modification: taking into account that sometimes being irrational can be fun, and because it’s fun there are more irrational actors around than you might otherwise expect.

Think about lottery-ticket buyers, Jouini says. The odds of winning the big prize are infinitesimal. But in the time between the purchase of the ticket and the confirmation that they’ve lost, people can at least dream about winning. And it’s rational to believe they derive some happiness from being irrational—even if they eventually lose out.

“We show that in some situations irrationality may persist just because irrationality is more rewarding in terms of happiness,” Jouini says.

Now that doesn’t mean that every irrational actor—or rock star—is going to survive. Jimi didn’t. Nor did Janis, Amy, or Kurt. But rock ‘n roll will never die—at least not while it’s still so much fun.