What’s happening to America’s accidental manufacturing renaissance?

Manufacturing in the United States, as in other developed economies, has been shrinking as a share of the economy for decades. Automation lowered costs and the need for workers, while globalization made the US less competitive, though it’s still the world’s largest manufacturer. But there was a surprising post-crisis manufacturing renaissance, which helped lead the US recovery in 2010 and 2011.

Manufacturing in the United States, as in other developed economies, has been shrinking as a share of the economy for decades. Automation lowered costs and the need for workers, while globalization made the US less competitive, though it’s still the world’s largest manufacturer. But there was a surprising post-crisis manufacturing renaissance, which helped lead the US recovery in 2010 and 2011.

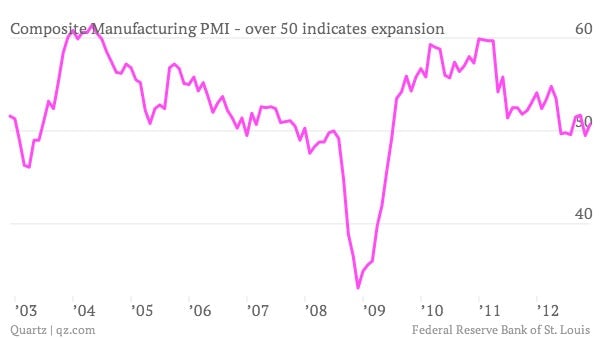

Now there are some early hints that it’s stuttering. In recent weeks, the Philadelphia and New York central bank branches have released reports on economic activity in their regions, and manufacturing there has fallen below expectations. Today’s report of unexpected contraction from the Richmond Fed makes a trend of three in a row. As the chart above shows, manufacturing in the US overall is still (just barely) expanding, but is well off its peak. Should we be worried?

Not yet, says Scott Paul, the president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing: “It’s probably too early to tell whether it was just a blip or whether it’s a trend.” Chad Moutray, the chief economist at the National Association of Manufacturers, says, “We’ve simply hit the pause button. Manufacturers are still cautiously optimistic about the rest of the year.”

Among the simpler causes of the pause are scheduled defense spending cuts, which would hit contractors making US war materiel. Last month’s “fiscal cliff” stand-off ended up postponing the cuts, but they could still kick in unless Congress reaches a more comprehensive budget deal soon, ideally avoiding more drastic consequences.

However, the reasons for both the post-crisis surge and the current slow-down are intertwined:

- Part of the 2010/11 surge was caused by pent-up demand, as consumers started buying again after the crisis. That demand has subsided somewhat, but consumer confidence remains fairly strong.

- Another part was the initial effects of the Obama administration’s auto rescue, which propped up car-makers and allowed them to become more efficient. They also benefitted from some of the pent-up demand.

- Productivity leapt during the crisis as manufacturers cut costs and laid people off. Those improvements are still helping businesses.

- Finally, the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing weakened the dollar against other currencies after the crisis, giving manufacturers an extra helping hand.

Those factors combined to create the surge. Now their impacts are waning, the dollar has strengthened again, and a broader global slowdown in Europe and emerging markets has reduced demand for American goods.

Still, there are a few reasons for optimism.

Dropping US energy costs due to fracking and higher wages for labor in countries like China are making American factories more competitive. Moutray reports that anecdotes of “reshoring”—American companies bringing outsourced production facilities back home—are becoming more common, although data on this are sparse.

Paul notes that manufacturing jobs have risen steadily. The sector added a net of 180,000 workers in 2012, mostly in the first half of the year, although that includes 25,000 in December. That suggests that companies are expecting more business. Even the Richmond Fed’s report noted that its contacts were optimistic about January.

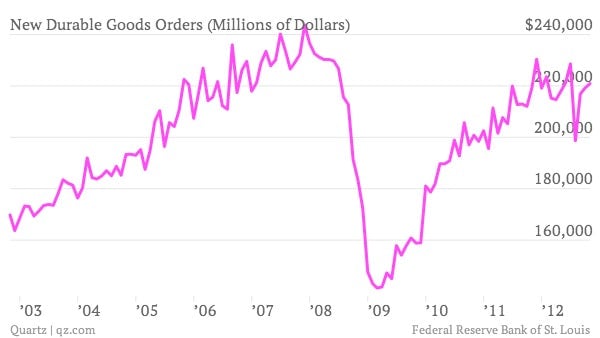

Durable goods manufacturers had the best of the post-crisis bounce, and have been rising again after sharp slide in late 2012; Moutray expects those conditions to remain in place in 2013 and 2014:

In short, it does seem like we’re seeing an end to the post-crisis surge. The question now is whether America’s domestic demand can combine with the energy revolution and other competitive advantages to return manufacturing to previous heights, or if a decelerating global economy will lead to an industrial slowdown in the US before those trends take hold.