China’s “new normal” is shifting the country’s economic center of gravity

Setting up shop in China used to be easy; open a flagship store in Beijing or Shanghai, or a factory in Guangdong, see what works, and then roll out to another of the hundreds of cities connecting over a billion people beyond.

Setting up shop in China used to be easy; open a flagship store in Beijing or Shanghai, or a factory in Guangdong, see what works, and then roll out to another of the hundreds of cities connecting over a billion people beyond.

But fundamental changes in China’s economy—both planned and unplanned—mean that companies marketing their goods in China, or looking for opportune manufacturing bases, are going to have a harder time finding their ideal city in which to set up and grow. That’s because local economies, pillar industries, and demographics are shifting so fast that even the best-looking cities five years ago have had huge reversals of fortune since, according to a new report from the Economist Intelligence Unit (registration required).

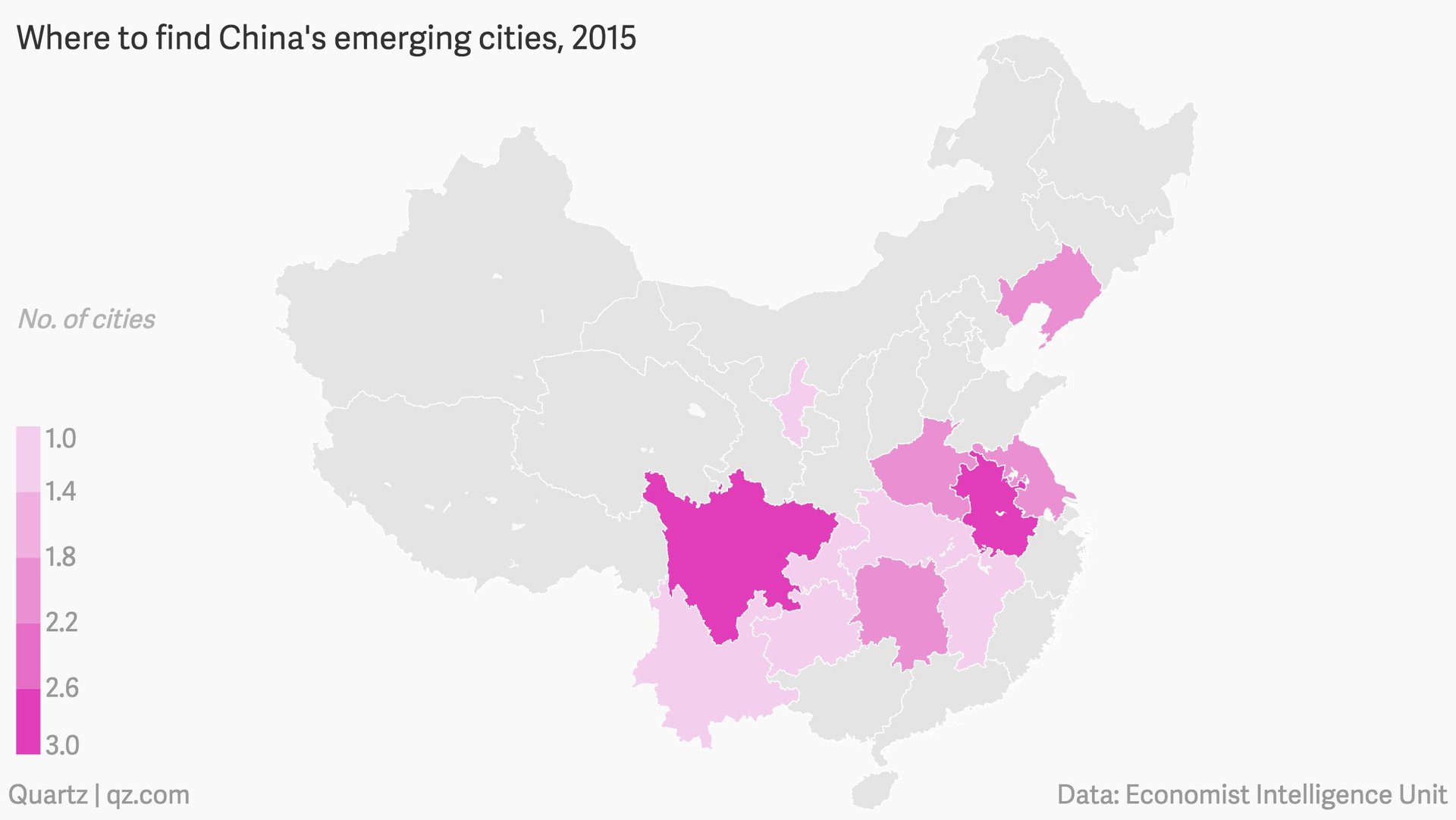

Of the 20 cities singled out in a 2010 EIU report as being China’s most promising, only six remain in the top 20 this year. And of six of 2010’s particularly hopeful, rockstar cities (Chongqing, Hefei, Anshan, Ma’anshan, Pingdingshan, and Shenyang), only one—Chongqing—remains in even the top 20 in 2015.

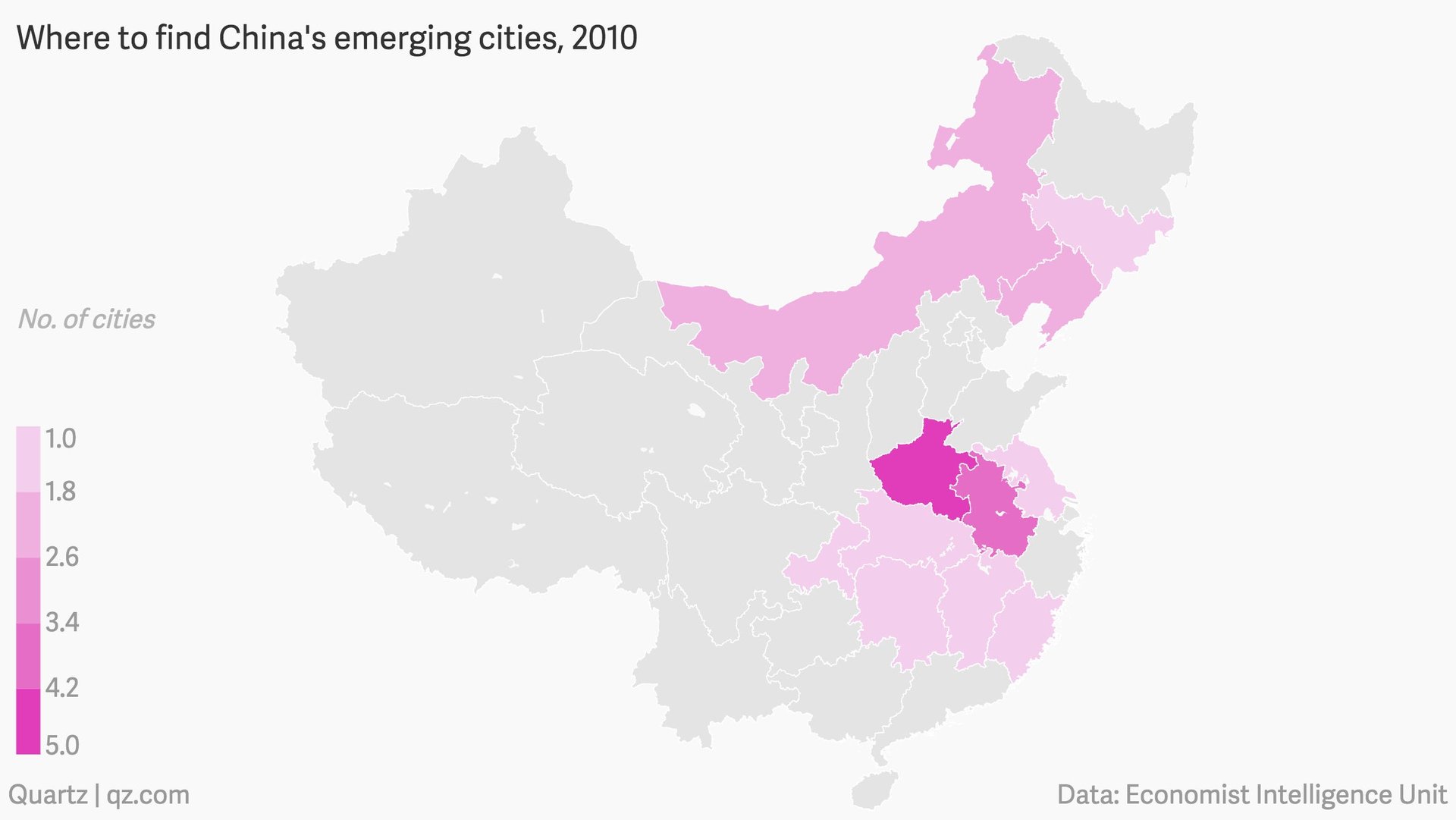

Most noticeable is the geographic shift of the 20 most promising cities. In 2010 these were found clustered around eastern ports and the northeastern industrial bases…

…And are now found among central and western provinces (China considers provinces “westerly” if they are not on the east coast):

Some formerly promising cities, such as those in the northeast’s rust belt, fell out of the top ranking because they were too reliant on heavy industry. That wasn’t a problem in 2010, but the global oversupply of commodities and a slowing property market has quickly turned what were strengths into weaknesses. Many of those cities now face a population decline as factories close and young people look for work elsewhere.

In other cities, organized labor has driven up the cost of doing business, making less-developed central and western cities more attractive in the process.

But it is not only because more developed cities are slowing that the rest of China is advancing. Smaller, poorer cities are also innovating their way out of the doldrums. Guiyang, capital of Guizhou, China’s poorest province, tops this year’s report as the most promising city in the country; it has achieved much recently through infrastructure investment, but most impressive is its ambition to become a ”data capital” of China.

The city has pledged to supply China’s biggest tech companies with efficient space for their servers, and has established a global big data exchange also. Last year it signed 132.6 billion yuan ($21.3 billion) in development contracts; Foxconn, the iPhone assembler, has agreed to develop technology parks in the city and semiconductor manufacturing bases, and along with Alibaba it has invested up to 3 billion yuan to develop cloud computing apps in the city.

Of course five years from now this could look as outdated as the rustbelt’s once-booming steel capacity, but for now it is a prime example of how China’s next generation of cities are building on brains, and not brawn.