ECB will become first major central bank to wind down monetary easing—starting next week

Next week the European Central Bank (ECB) will be the first of the world’s major central banks to start winding down its unprecedented monetary easing programs. These programs have led to record low interest rates worldwide, and we’ve written extensively on the sometimes peculiar effects of these low rates. But the ECB will become the first to actually reverse this program starting next week.

Next week the European Central Bank (ECB) will be the first of the world’s major central banks to start winding down its unprecedented monetary easing programs. These programs have led to record low interest rates worldwide, and we’ve written extensively on the sometimes peculiar effects of these low rates. But the ECB will become the first to actually reverse this program starting next week.

As credit conditions contracted sharply at the end of 2011, the ECB pumped money into the system through two long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), which encouraged banks to lend to one another again. It also encouraged them to buy the debts of Italy and Spain. The LTROs offered banks the chance to hang onto the cash for a full three years, but only forced them to accept the funds for a year. The LTROs served as massive non-traditional monetary easing; after all was said and done, the ECB ended up injecting a total of €1.02 trillion ($1.36 trillion) into the money system through the banks.

This is different from the loose monetary policy that most central banks have in place. The Federal Reserve, Bank of England, and Bank of Japan have used “quantitative easing”—buying up government bonds and other “safe assets”—to stimulate economic growth. In both cases, those policies have pushed down the value of these currencies.

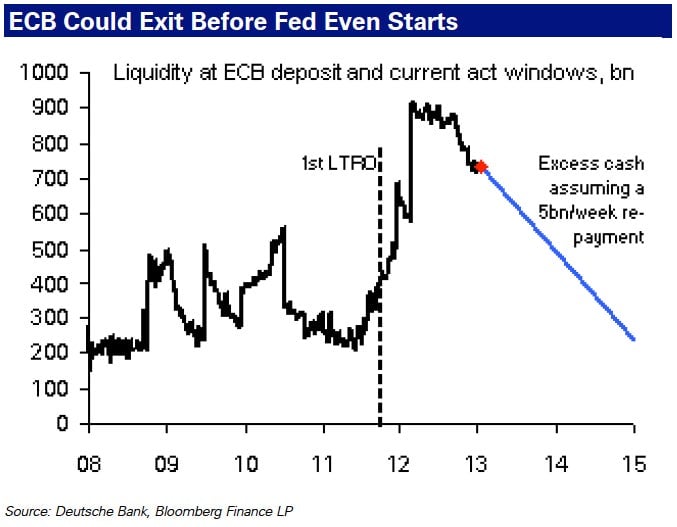

While the Fed recently hinted that it might start to stop purchasing assets this year, and has occasionally done so before, it has never yet sold them off back into the market. But banks that borrowed from the ECB in its first refinancing operation can choose to start repaying that money beginning Jan. 30, thus diminishing the liquidity in the system. Danske Bank estimates that banks will return €75-100 billion ($100-$133 billion) at the first repayment date; Deutsche Bank estimates €100-200 billion. Thereafter, they can continue to pay every week (see chart below).

Of course, this isn’t a change in ECB policy: It was part of the plan. Nor does it rule out more easing in the future—for example, “outright monetary transactions” in which the ECB would purchase a country’s bonds after it requested aid. Nonetheless, it does actually roll back—rather than just halt—the expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet. This is something no other central bank is doing right now, and it could have various consequences.

One, which we pointed out a few weeks ago, is a risk to weaker banks. Some analysts have worried that banks that can’t yet afford to pay back the cash—particularly in Spain and Italy—will do so anyway in an attempt to look stronger than they are. This would leave them high, dry, and illiquid in the event of a sudden shock to markets.

Many investors are no longer too concerned about this risk, however. “The larger banks running huge surpluses will return funds but the smaller ones won’t. People are now past the point where they worry what other people think,” says Steve Collins, Global Head of Dealing at London & Capital.

More immediately, the winding up of the LTROs equates to a gradual tightening of monetary policy. Though the ECB isn’t actually raising its interest rate, the monetary tightening “has the potential to lead to “stealth” rate hikes even before the Fed ends QE,” writes Deutsche Bank strategist George Saravelos in a note published today. Theoretically, this will make credit more expensive in euro land and cause the euro to appreciate. An expensive euro could be cause for concern if a currency war erupts, and tighter credit conditions are not what the still-fragile European banking sector needs.

Some see this tightening as something to welcome, not worry about. “If we see a gradual payback of the LTRO money, this should be viewed as a positive factor for risky assets as it indicates that the funding markets for banks is continuing to improve, and that banks no longer need to be dependent on the ECB. So, even though the significant excess liquidity would decline, it should be seen as a positive factor for the market, also in the case of short rates beginning to rise,” writes Danske Bank senior analyst Peter Possing Andersen.

George Saravelos, FX strategist at Deutsche Bank, is more cautious. “Ultimately, and as the 2008 and 2010 experiences showed, premature tightening may force the ECB to backtrack and may even make the Eurozone crisis worse later in the year.”