A strong euro is the last thing Europe needs if currency war dawns

Yesterday Jean-Claude Juncker, who presides over meetings of European finance ministers, complained that the euro’s value has become “dangerously high.” The comments took many by surprise; it’s when the currency has been strongest that investors have shown the most faith in the euro’s continued survival. Indeed, growing faith that the euro zone will in fact stay together has left traders crowing about a “big leap in bullish sentiment,” in the words of Morgan Stanley’s currency team. The euro hit $1.34 on Monday—its highest value since February 2011.

Yesterday Jean-Claude Juncker, who presides over meetings of European finance ministers, complained that the euro’s value has become “dangerously high.” The comments took many by surprise; it’s when the currency has been strongest that investors have shown the most faith in the euro’s continued survival. Indeed, growing faith that the euro zone will in fact stay together has left traders crowing about a “big leap in bullish sentiment,” in the words of Morgan Stanley’s currency team. The euro hit $1.34 on Monday—its highest value since February 2011.

But ironically, this renewed faith in the euro currency comes at the worst possible time for the euro-zone economy. Although policymakers finally appear to be making a concerted slog towards union, the years of political turmoil have severely stunted investment in the euro zone, leading to a collapse of the region’s economy. Greece’s recession has turned into a depression in its sixth year. A quarter of the Spanish populace is out of work. Even normally resilient Germany has succumbed: growth in industrial production is stalling, and the country’s GDP fell at a rate of 0.5% in the last quarter of 2012.

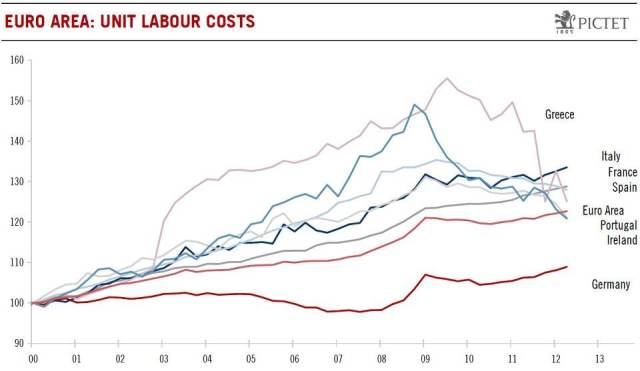

For the euro zone economy to rebound and grow in the long term, labor in peripheral Europe needs to get cheaper. Growth policies and austerity measures that Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, and Spain have passed in the last few years have all included pension cuts, wage decreases, union protections, and the like in an attempt to draw investment in the production of goods. It’s a slow and painful process, but there are signs these policies are working, even if they are depressing economies in the short term. In these peripheral countries, labor is indeed becoming cheaper, as the chart below shows.

That whole plan gets shattered if the euro gets pricier. If the euro appreciates, goods made by European workers become more expensive in other currencies. That cripples exports and hurts already struggling economies. Although a slow equalization in labor costs within the euro area may continue to happen, a decline in exports would hurt everyone.

The blame for a more expensive euro can be squarely placed on the shoulders of the world’s main central bankers and the monetary-policy activists who influence them. The election of Shinzo Abe in Japan and continued murmurings out of the Bank of Japan indicate that monetary easing is likely to bring down the value of the yen, which has already fallen considerably in the last few months. Continued and unlimited quantitative easing—jokingly dubbed “QE-infinity”—in the US is only helping deflate the US dollar. Meanwhile, officials at the European Central Bank continue to stubbornly refuse to cut interest rates, even though credit remains tight in Europe.

Russia’s central bank today joined the small chorus of voices warning of a currency war, which could entail rounds of easing and interest-rate cutting around the world, both in emerging and advanced economies. If unsteady peripheral Europe is trying to make its labor and its exports cheaper, then what seems like a budding global battle to be the cheapest currency is a worrisome sign at an already terrible moment.