How China’s fish bladder investment craze is wiping out species on the other side of the planet

Another asset bubble has burst in China. And it’s not in stocks, metals or real estate. It’s the market for a maize-colored organ carved out of a giant, endangered Mexican fish.

Another asset bubble has burst in China. And it’s not in stocks, metals or real estate. It’s the market for a maize-colored organ carved out of a giant, endangered Mexican fish.

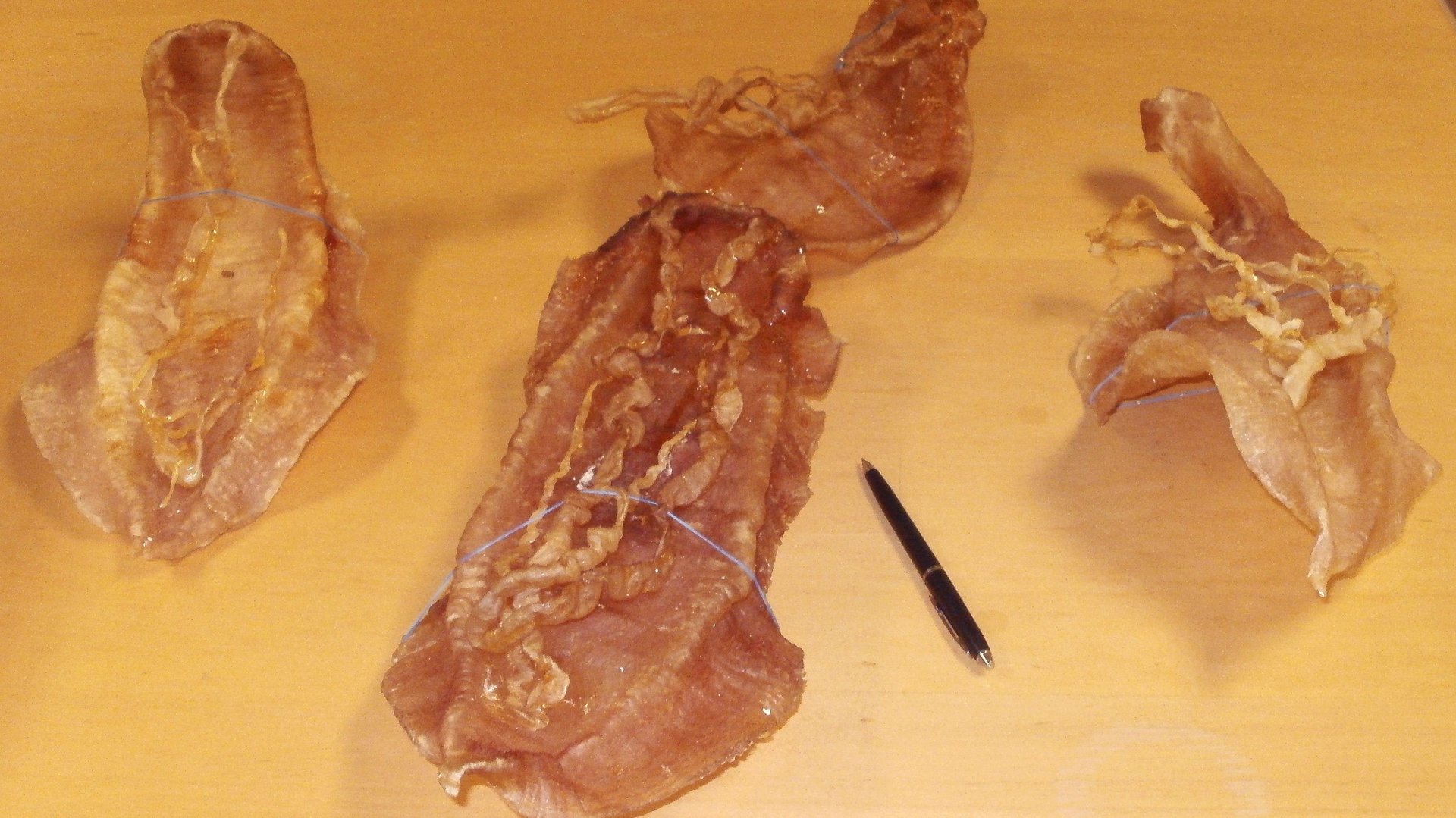

The totoaba, as the fish is known, uses this organ, its swim bladder, to regulate buoyancy. For centuries, wealthy Chinese have prized such bladders, what they often call “fish maws,” for making soups thought to ease the discomfort of pregnancy and cure joint pain, among other ailments—and sometimes as speculative investments. In 2011, a single totoaba bladder could fetch as much as HK$1,000,000 (then about $137,000) in Hong Kong or Guangzhou, according to Greenpeace Asia, a nonprofit group. But these days, that same bladder is worth a mere HK$200,000.

The story of how the bladder bubble inflated and then burst is a classic tale of globalization—of the intersection between monetary policy, financial markets, luxury goods, international regulation, and transnational crime. It’s also an all-too-familiar and depressing environmental tale, because while the bladder trade has endangered the totoaba, it’s driven the vaquita—a tiny porpoise that’s prone to getting tangled up in totoaba nets—almost to extinction.

Fortunately for both animals, after years of lax enforcement, the Mexican government is finally cracking down on illegal totoaba fishing in waters the vaquita inhabits. There’s a glint of hope that their populations might recover from the spectacular carnage of the last few years. Ultimately, though, the fate of both animals will depend not on the zeal of Mexican authorities but on the whims of wealthy Chinese investors—and whether they start betting on bladders once again.

Strange contraband

Of all the organs of all the fish in the sea, the totoaba’s swim bladder must claim the prize for grabbing the most headlines of late.

On July 25th, during a routine luggage scan, airport officials in the Mexican border city of Tijuana arrested three Chinese nationals (link in Spanish) who had stashed 247 totoaba bladders, swaddled in plastic and paper towels, in their suitcases. Days earlier, the owner of a Los Angeles furniture company pleaded guilty to importing millions of dollars worth of bladders and other illegal seafood into the US from Mexico. A week before that, customs officers in Puerto Rico seized nine parcels containing more than 1,300 pounds (600 kg) of bladders shipped from Venezuela en route to Hong Kong.

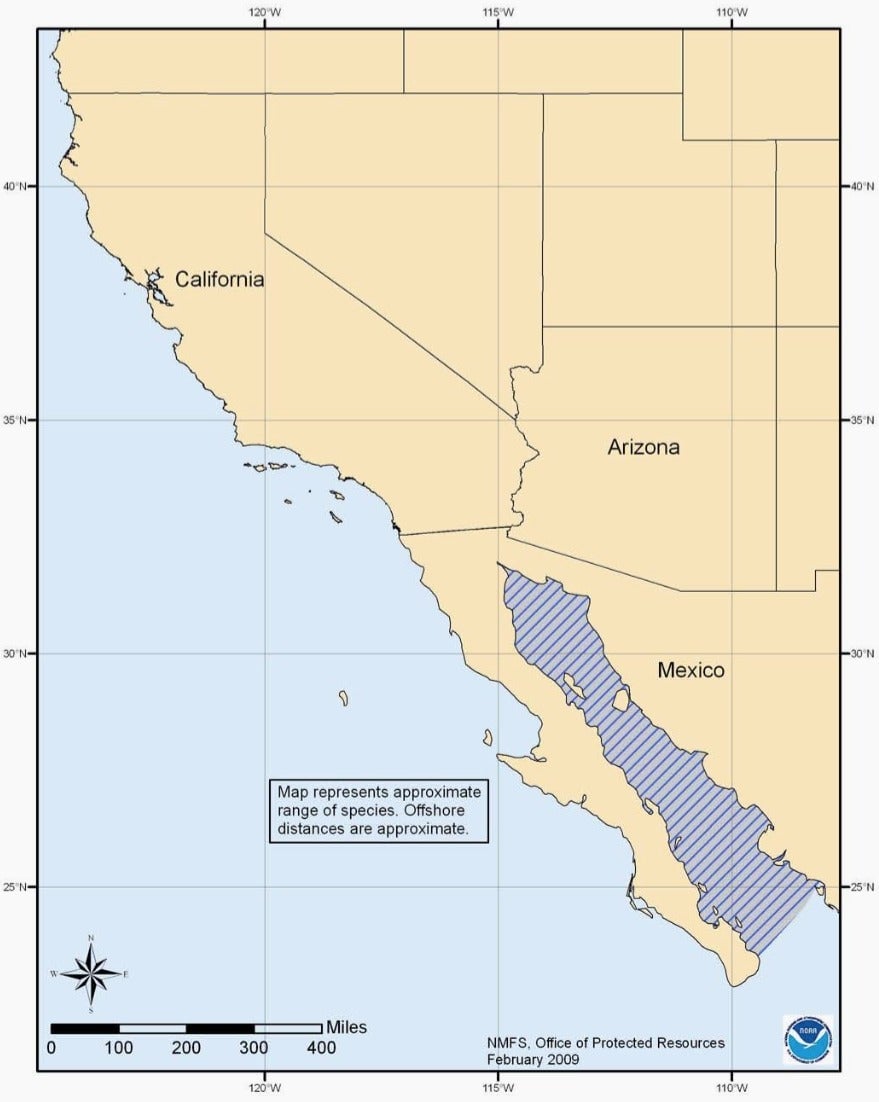

The source of all this contraband was the upper Gulf of California, the arm of sea that reaches up between Baja California and mainland Mexico. The totoaba, an ancient-looking fish that can grow up to 7 feet (2.1 meters) long, lives only in these waters. Chinese emigrants to the area discovered it in the early 1920s.

It resembles the giant yellow croaker, a similarly huge fish native to China’s southern coast, whose bladder fetched handsome prices in seafood stalls for use in a traditional soup with supposedly medicinal properties.

In the early days, fishermen harpooned totoabas or caught them with fishing lines from the shore, selling the bladder for export to Asia. The meat was either sold locally or shipped to the US. But the bladder was far more valuable; by 1942, there were reports of totoaba carcasses littering the beach, their bladders cut out.

With the introduction of gillnets in the mid-1960s, the huge fish all but disappeared (though environmental destruction resulting from the Hoover Dam contributed too). In 1945, upper Gulf fishermen landed more than 2,200 tonnes (2,425 tons) of totoaba; by 1975, they caught a mere 58 tonnes. That year, the Mexican government closed the fishery; soon thereafter the totoaba was added to the endangered species list.

The totoaba’s Chinese cousin

The giant yellow croaker—also called the Chinese bahaba—can span up to 6 feet and weigh 100 kilograms (220 pounds). It once flourished in the stretch of sea from the Yangtze estuary to Hong Kong. Today, however, it hovers on the brink of extinction.

For more than a millennium, fish maw has been a favorite dish at fancy Chinese banquets, celebrated in large part for its supposedly medicinal properties. The bigger the bladder, the steeper the price. Those sliced from smaller species on the croaker family tree were commonly used in cooking, while the much larger specimens that came from the giant yellow croakers cost many times more and were consumed typically for specific medical benefits.

Nonetheless, until a few decades ago, croaker populations held steady. The 40 or so boats that hunted them when they swarmed the mouths of the Yangtze and other southern Chinese rivers to spawn usually landed a few dozen fish a day. But the use of mechanical engines, which took off in the 1950s, changed things dramatically. Suddenly boats were returning with hundreds—sometimes even a thousand—giant yellow croakers a day, according to research by Yvonne Sadovy, an expert on the bladder trade at the University of Hong Kong.

This over fishing decimated the croaker population. In the late 1930s, boats hauled up 50,000 tonnes of giant yellow croaker a year; three decades later, it was as little as 10 tonnes. Another effect was to sharply reduce the average size of the croakers caught. As a result, the price of large bladders soared. While in the 1930s, they sold for a few US dollars, a large bladder cost as much as $1,000 ($6,500 in 2015 dollars) in 1969. By 2000, they were going for $21,800. In real terms, that means the price multiplied nearly fivefold in a mere three decades.

A bladder for a rainy day

But millions of Chinese didn’t suddenly develop a appetite for bladder soup, says Sadovy. What drove the demand was that in times of strife, Chinese households have been known to stockpile the more valuable bladders as speculative investments, on some occasions even trading them as currency.

That’s what happened after the 2008 global financial crisis hit. The Chinese government reacted with a stimulus package that sent easy money sloshing around the economy—adding up to 17.5 trillion yuan ($2.8 trillion) in 2009 and 2010 (paywall). Cash flooded into a dizzying array of speculative assets, from property and copper to modern art to pu’er tea—and totoaba bladders. Traders in Hong Kong tell of selling large bladders for HK$1 million ($130,000) in 2011 and 2012, according to a recent Greenpeace East Asia report (pdf). These merchants emphasized that buyers weren’t interested in health tonics; they were snapping up these “cash bladders,” as they call them, as investments.

Though the trade in bladders is illegal, Hong Kong customs authorities are very lax about screening for them, traders told Greenpeace. That makes Hong Kong the bladder trade’s entrepôt. From there, the contraband is smuggled past mainland China’s more vigilant border agents, and sold in China’s major cities.

The bladder bubble builds—and bursts

Since the late 1970s, catching the endangered totoaba has technically been illegal. But Mexican authorities have seldom enforced the ban, says Andrew Johnson, a researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, who studies Gulf of California fisheries. When the 2008 crisis hit, tourism—a leading industry in the upper Gulf of Mexico and the major alternative to shrimping and fishing—foundered. Totoaba bladders, however, offered a quick profit.

“A fishermen can make $3,000 to $4,000 for a swim bladder—it’s a good living to catch just one,” says Johnson. A big fish, in other words, could be worth three or four months of work.

The Chinese investors’ appetite for bladders, the economic slump in Mexico, and lax enforcement created a perfect storm. Signs of the totoaba slaughter began showing up in the upper Gulf of California around 2011, says Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, head of marine mammal conservation and research for the National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change (INECC) in Mexico.

“Everybody knows that there has always been some totoaba fishing. But then everywhere you go there were plenty reports of totoaba nets and fishing—even reports of totoabas being thrown on the beach with their swim bladders removed,” he says. “You could suddenly see new cars and trucks in the fishing villages of the upper Gulf.”

Some of this trade went by the Tijuana route; between February and April of 2013, the US border patrol busted seven people in five different operations, seizing hundreds of pounds of bladders. But around this time, smugglers also began exporting the contraband straight from Mexico to China, says Johnson.

By 2013, so great were the influxes of totoaba bladders into Hong Kong that they began driving down prices, Hong Kong traders told Greenpeace. The Environmental Investigation Agency’s recent research corroborates that drop. “Prices have dropped considerably in recent years due to the massive poaching of totoaba and oversupply,” says Clare Perry, leader of the oceans division of the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a nonprofit group. “So traders are hanging onto stock in the hope that the prices will rebound.”

Little cows to the slaughter

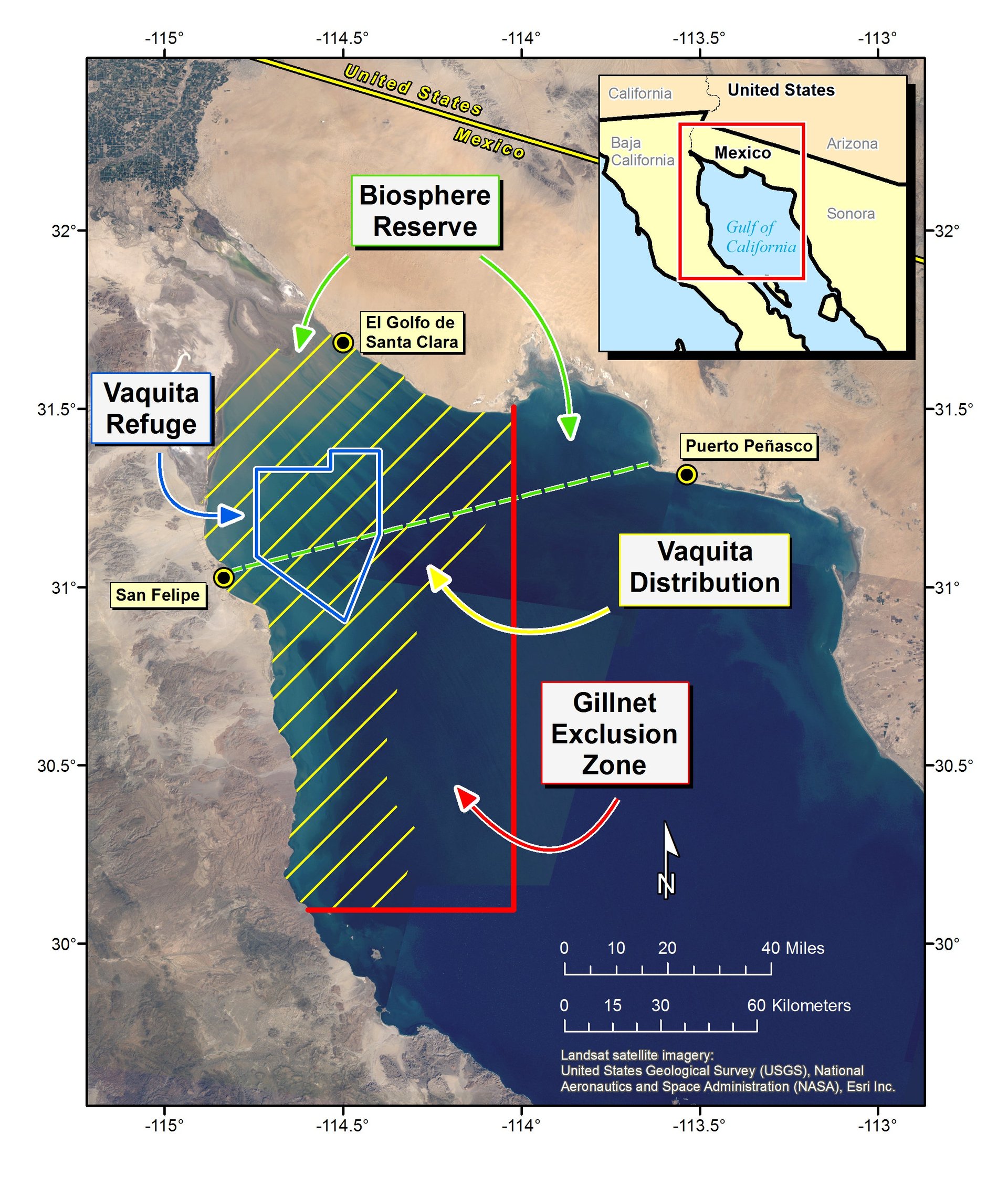

The totoaba, however, wasn’t the only victim of the Chinese bladder boom. So was the vaquita (“little cows” in Spanish), a small porpoise that lives only in a patch of the upper Gulf of California, one quarter the size of Los Angeles. Vaquitas are easily tangled and killed in gillnets used to catch shrimp and other seafood. However, the nets used for catching totoaba are particularly treacherous, says Rojas-Bracho, because their mesh is about the same size as a vaquita’s head.

Though vaquita numbers had been shrinking at an alarming clip since the 1990s, Rojas-Bracho says that by 2008 that rate of decline had slowed, likely as a result of a government effort to reduce fishing—including declaring a patch of sea to be a vaquita refuge in 2005. But then things got abruptly worse. Acoustic monitoring data showed a 67% drop in vaquita activity between 2011 and 2014. ”What really [has been killing the vaquita],” says INECC’s Rojas-Bracho, “is the incredible demand for totoaba swim bladders, which have become, as a colleague of mine says, like the cocaine of the sea.”

That may finally be changing. In April this year, the Mexican government launched a two-year ban on the use of gillnet fishing throughout the vaquita’s reported range—an area six times bigger than the 2005 vaquita refuge—as well as subsidies for fishermen who give up dangerous gear. The new ban came with teeth, in the form of an interagency federal enforcement program outfitted with high-powered speedboats.

So far, this seems to have deterred fishing, says INECC’s Rojas-Bracho. But the vaquita is pretty slow at breeding, so the gillnet ban will have to be in place for far longer than the current two years to work. Even then, he says, we won’t see a full vaquita recovery in our lifetimes.

Whatever the vaquita’s fate, the totoaba’s is also still unclear. The stepped-up enforcement is keeping some gillnet fishermen off the water and may encourage them to change jobs. But others are already casting their gillnets at night, or to the south of the protected area, says Rojas-Bracho, in search of totoaba to supplement their income. And while the current glut of totoaba bladders may keep prices down in China for a while, tougher enforcement will eventually shrink supply. When that happens, prices will climb once again—making the temptation to plunder the giant fish even harder to resist.