Does an unexpected glut of new homes mean it’s time to worry about US growth?

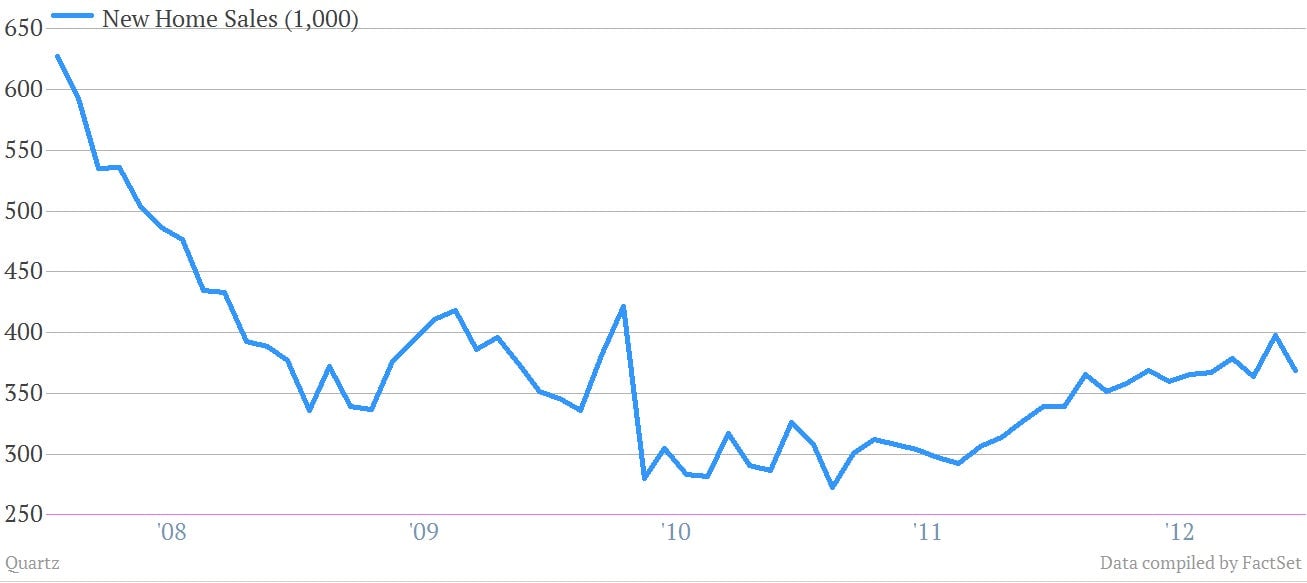

Last year was a good one for the US new-homes market: 367,000 were sold, up 19.9% from 2011. Though December’s data came in lower than expected, 2012 as a whole did something huge: It reversed a six-year trend in declining sales of new homes.

Last year was a good one for the US new-homes market: 367,000 were sold, up 19.9% from 2011. Though December’s data came in lower than expected, 2012 as a whole did something huge: It reversed a six-year trend in declining sales of new homes.

There’s a nagging detail, though, in what wasn’t sold. The number of new houses for sale hit 151,000 by the end of December, an inventory that would take 4.9 months to sell at the current pace of sales, an increase from November. With “the pace of new residential building activity now approaching 1 million units, the impending surge in new homes supply could create a problem for this segment of the housing market, unless there is a commensurate increase in demand,” wrote TD Securities analysts.

In other words, a glut of new houses could whack prices, halting their steady upswing since last spring (pdf).

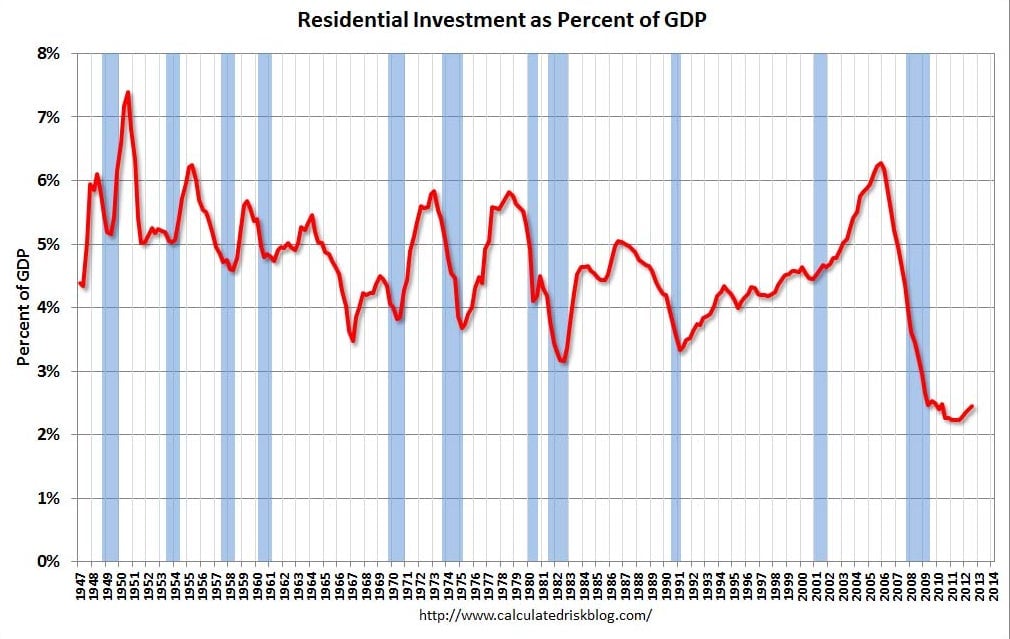

That would deal a big blow to the US economy. Demand for new housing is a key driver of residential investment. And, as many have noted, residential investment is typically a hefty component of US GDP—which explains why the recovery from the financial crisis has been so sluggish. A drop-off in demand could spur a contraction in investment, dragging down housing starts and taking the US GDP with it.

It could. But a closer look at Tuesday’s data on existing-home sales suggests that it won’t.

Existing-home purchases account for more than 90% of the total—and the supply of those has been contracting lately. Inventory for existing homes plummeted in 2012, falling 22% since 2011, according to the National Association for Realtors. It would now take a mere 4.4 months to clear the total housing stock for sale; in December 2011, that figure was 6.4 months.

That low supply likely results not so much from excess demand as from people not selling. Of course, they’re kind of the same thing. Many potential buyers are first and foremost sellers. That means the conditions for selling and buying both need to be sound before these potential seller-buyers trade up for a more expensive home, a process called “turnover.” And right now, even with a housing recovery supposedly underway, neither factor has changed decisively enough to spur turnover. Calculated Risk passes on Merrill Lynch’s analysis of this trend:

[T]he decline in turnover … is the main reason for lean inventory of existing properties. This is a function of 1) falling home prices, which discouraged sellers; 2) tight credit, which reduced the number of move-up buyers; 3) negative equity that led to lock-in.

But wait—haven’t prices been rising? And hasn’t the Federal Reserve made credit much easier?

Prices have been ticking up, but they’ve been doing so inconsistently. A look at the Case-Shiller index (pdf) shows that the recovery in prices has been both geographically and seasonally uneven. From the perspective of individual homeowners, both of those factors can obscure what looks from 30,000 feet like a clear uptrend. As that price-trend clarity develops and as construction revs up—particularly in underserved markets—willingness to sell should build. In addition, the overall tight inventory should help keep new home prices up.

Then there’s credit. Despite record-low mortgage rates, restrictive mortgage underwriting standards continue to curb sales, says NAR chief economist Lawrence Yun. Tellingly, all-cash transactions made up 29% of purchases in December, compared with a usual share of around 10%, according to First Trust Economics Blog (pdf). Perhaps the return of the Big Banks into the mortgage business will help flush some credit into the system, providing a crucial bump-up in demand.

The improvement of both of these factors should encourage current home-owners to sell. This will, of course, add to the supply of existing homes. But some of those trading-up homeowners will spring for new houses too. That should mop up any worrying excess in new-home inventory. Both new- and existing-home inventory figures should signal whether to expect more of that 2012-era good news on the housing recovery as 2013 unfolds.