Kenya and Uganda have agreed on a route for a 1,500-km (930-mile) pipeline to pump oil from Uganda to the Indian Ocean, a project that officials hope will transform East Africa into a major oil exporting region.

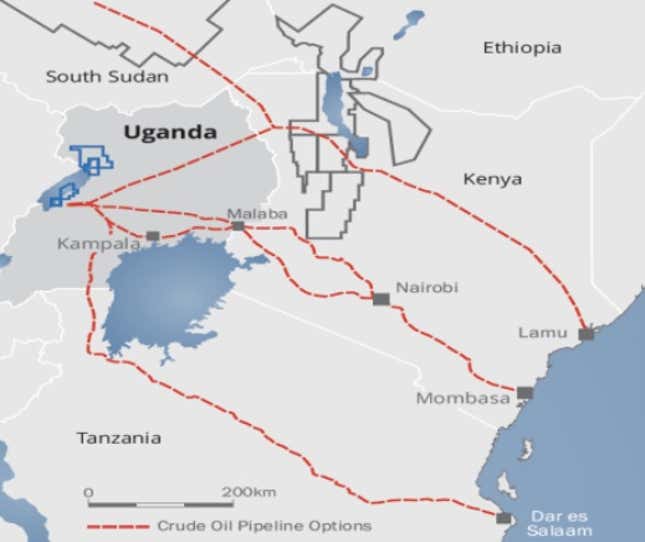

The path—to serve Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, and potentially Ethiopia—has been the subject of dispute between Kenyan and Ugandan officials since last year. It will cut through northern Kenya and the Lokichar Basin from Hoima in western Uganda before reaching the port city of Lamu.

An alternative route had the pipeline snaking through Kenya’s capital of Nairobi and on to Mombasa, a plan that Ugandan officials said would be cheaper, but would have required displacing hundreds of residents.

The pipeline is part of a broader regional project, the Lamu Port Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor, to bring Ugandan and Kenyan oil to global markets. Uganda is home to sub-Saharan Africa’s fourth-largest supply of crude oil, with as much as 6.5 billion barrels discovered a decade ago. Kenya is home to about one billion barrels. Another proposed project would connect oil from South Sudan and Ethiopia to the pipeline.

But the project is not without its risks. Falling oil prices have derailed other less challenging projects. The pipeline will be the world’s longest heated oil pipeline (pdf, p. 45) as well as one the region’s most ambitious infrastructure projects. (Because Ugandan and Kenyan oil is waxy, it will have to be constantly heated.)

The pipeline will likely have to travel through swamplands, national parks, and wildlife reserves, and parts of northern Kenya that are vulnerable to attacks by bandits or Islamist militants, according to consultancy BMI Research, which estimates the pipeline won’t be ready before 2020. A lack of skilled labor, poor electricity supply, and the difficulty of importing material and machinery into landlocked Uganda are other obstacles.

It’s also not clear who will bear the costs of the pipeline, which authorities said is still subject to financing and security guarantees. The project is estimated to cost around 404.8 billion Kenyan shillings ($4 billion)—the World Bank has pledged just 54 million shillings.