BP and ExxonMobil take up opposite sides of the front lines in Iraq

For more than a year, ExxonMobil has stood as the backbone of Kurdistan politics, validating its independence as a global petro-player. Now, BP has taken up the mantle for the opposing side, shoring up Baghdad in a tense standoff at the city of Kirkuk.

For more than a year, ExxonMobil has stood as the backbone of Kurdistan politics, validating its independence as a global petro-player. Now, BP has taken up the mantle for the opposing side, shoring up Baghdad in a tense standoff at the city of Kirkuk.

In doing so, it may be the first time in modern oil’s century-and-a-half-long history that oil companies have taken up front-line positions as the allies of opposing armies.

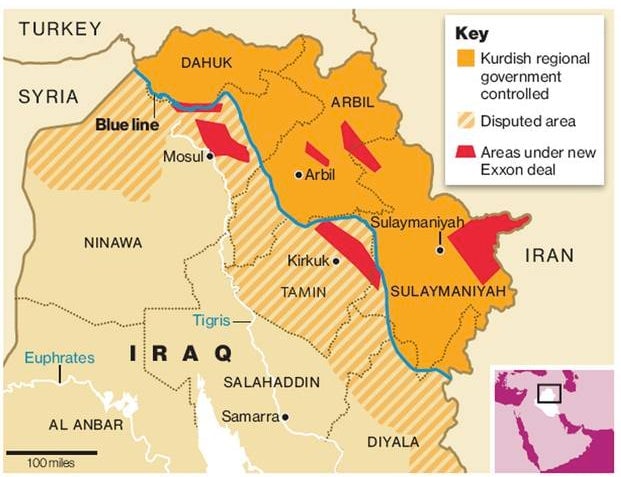

In summer 2011, ExxonMobil decided to flout a Baghdad dictum against signing oil deals in Iraq without its permission, and negotiated a rich drilling contract with the autonomous region of Kurdistan. As you can see in the map below from the Independent, the deal encompassed disputed provinces just between Kurdistan and Kirkuk. Kirkuk is the principal fault-line between the two sides, the site of a massive oilfield that both claim.

ExxonMobil’s weight (see No. 10 in Quartz’s indicators of energy geopolitics) conferred legitimacy on the hitherto shaky Kurdistan government, leading other oil majors such as Chevron and France’s Total to sign deals with the Kurds as well.

But some in Baghdad are treating ExxonMobil’s behavior as hostile. In December, an Iraqi official said, “If Exxon lays a finger on this territory, they will face the Iraqi Army.” Meanwhile, Baghdad and Kurdistan have rushed their armies to the Kirkuk area. On Jan. 16, a car bomb in Kirkuk killed four people (see photo above).

Now, in BP, Baghdad is–figuratively speaking–dispatching more artillery to the front. In mid-January, Baghdad signed a preliminary deal with the British company to develop the Kirkuk field, just west of ExxonMobil’s area. But Kurdistan claims rights to the same field. And, just as Baghdad has objected to the agreements signed by Exxon and the others in the north, Kurdistan has rejected the BP deal in Kirkuk, complaining that any such agreement must be approved by all parties in the dispute.

The deal–in which Baghdad has moved to trump Kurdistan–puts the two companies on opposing sides of the battle line.

In doing so, Baghdad capitalizes on the clout of its closest remaining ally among the international oil companies. While many of the companies have fled to better terms in Kurdistan, BP has almost alone stayed back, largely because it always had the best deal of any of them, working the gigantic Rumaila oilfield in the south.

“All that we have done is made a proposal for short-term assistance, which the Oil Ministry appears to like, and we are progressing on that,” said BP spokesman Toby Odone. “It is early days though.”An ExxonMobil spokesman declined to comment.