“Pink Floyd is dead. I’m ready to move on.”

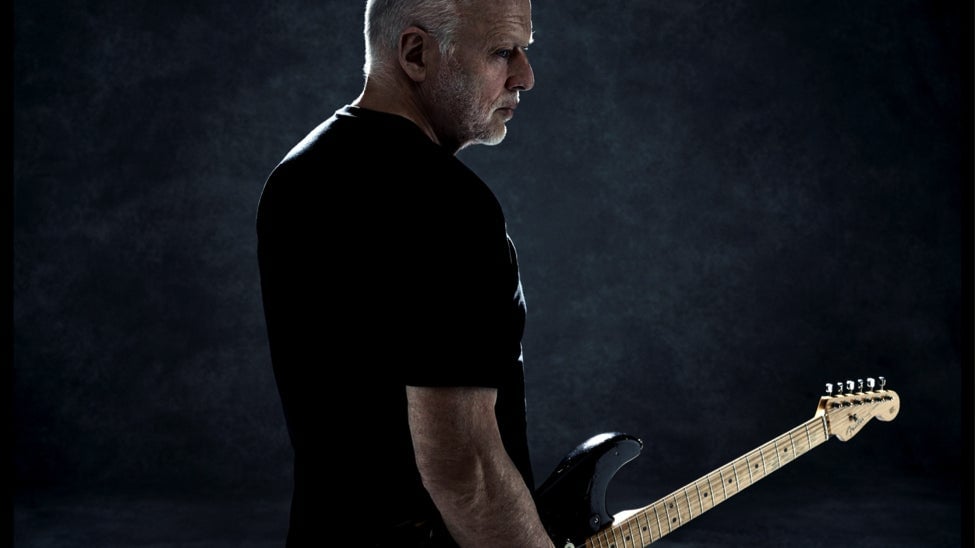

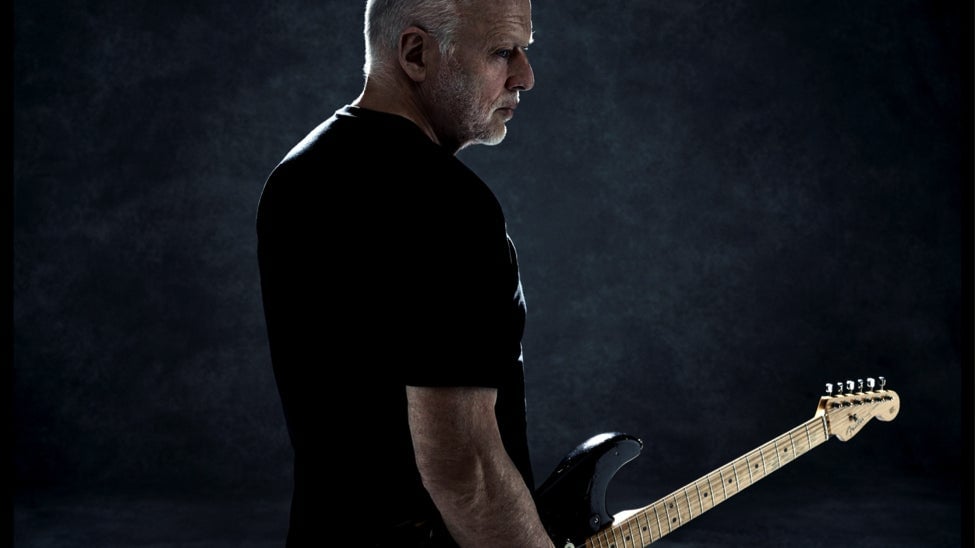

David Gilmour speaks in an online exclusive on the end of Pink Floyd and his new beginnings at 69.

David Gilmour speaks in an online exclusive on the end of Pink Floyd and his new beginnings at 69.

“I wish I could say there was a plan, but there never seems to be one,” David Gilmour, the man whose distinctive voice and guitar defined Pink Floyd tells me when I mention that there are as many new and unexpected sounds as there are echoes of his former group, Pink Floyd, on his new album. “I just move on, trying to find something that is of the moment (of creation) and of the song. I can’t really describe how that process works and happens, but it’s more luck than anything. You just find something and go with it.”

Gilmour’s modesty aside, Rattle That Lock, his new solo album, due out on September 18th, has plenty of his trademark guitar–sometimes mournful, sometimes piercing and sometimes both–over ambient soundscapes of the sort that Pink Floyd were known for. But it’s also full of new ideas. There’s a bit of jazz here and there, as well as some very un-Floyd, almost pop sounding tunes.

“Pink Floyd is dead, I think. I’m ready to move on,” Gilmour tells me, sitting in his long-time publicists office in London, when I ask him if there will ever be any live shows, like the band’s reunion at Live8, or more recordings, like last year’s phenomenally successful album The Endless River, which Gilmour and Floyd drummer Nick Mason crafted from recordings they had made originally during the sessions for 1994’s The Division Bell with keyboardist Rick Wright, who died in 2008. “When I was played the tapes we’d made with Rick, it felt like such a shame for us not to do something with them. I was glad we were able to make something that I think was really special out of them, and it was really built very much around Rick’s character, in many ways.”

Gilmour also makes it clear that, with Wright’s passing, there is nothing left of Pink Floyd in his mind.

“When Rick died, that was really and truly the end,” he says, without a hint of regret. “I know Nick says that he lives in hope that we’ll do something more, but it’s easy for him to say that, as the drummer. There’s much more responsibility up front for me, and there’s no way that I can foresee working with Roger, certainly not on the sort of scale that it would be if it were Pink Floyd.”

Roger is, of course, Roger Waters, the principal lyricist and a huge guiding force in Pink Floyd until his abrupt departure in the mid-1980s. After a flurry of lawsuits and backbiting in the press, a Gilmour-led Pink Floyd released two studio albums, two live albums, and toured to great acclaim until 1994. And then the band seemed to just stop.

After twenty years The Endless River picked up where Pink Floyd had left off. But in the meantime Gilmour had periodically dipped his toe in the water as a solo artist–sometimes with Wright along for the ride–and appeared to revel in the freedom he’d found.

Gilmour released the tentative, but interesting David Gilmour in 1978, followed by About Face in 1984, in the midst of his war with Waters. It wasn’t until 2006 that he released another solo album, the worldwide smash On An Island, which he toured the world in support of.

Each album was another small step on the road away from the “lurching monster,” as Gilmour calls it, that is Pink Floyd. With Rattle That Lock, it seems, Gilmour has finally found firm footing as an artist in his own right.

But, like Pink Floyd’s best work, the songs are built around a loose concept–“it’s a day in the life,” Gilmour says, “beginning at 5 AM and flowing on to night”–and, perhaps even more fittingly, the ghost of a lost friend hangs over the proceedings.

“The song ‘A Boat Lies Waiting’ was certainly an elegy of sorts for Rick,” Gilmour confesses. “The funny thing is it’s quite an old song. I played the piano on it, and it does quite sound like Rick. It just came to me naturally. I’m not sure from where or how. But it was long before Rick died that that piece of music came about. You can hear my son, who’s now 20, as a newborn baby, three months old or something, squawking on that track. So that tells you how old that one was.”

Fittingly, as a member of the band that every high-end stereo store play as test subjects for would-be customers, owing to its groundbreaking, pristine recordings, Gilmour has fully embraced technology, and has several full-blown studios at his disposal.

“The studio at home I use in Brighton these days has a full Pro Tools (recording software) rig,” Gilmour explains. “It has a control room and a separate recording room. I spend 95% of my time just in the control room where I play everything myself. It’s fairly elaborate. It just doesn’t have a proper desk.”

He also has an antique houseboat, known as the Astoria, where he has recorded at least part of every album he’s worked on since Pink Floyd’s first post-Waters album, 1987’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason.

“I like the Astoria because the Astoria has a full mixing setup,” Gilmour explains. “But it’s also a lovely space, with windows on the river. It’s one of the perks of the way I’m able to work, certainly.”

He’s also embraced technology on a much smaller scale in order to help his songwriting and creative process along, having used his iPhone to record at least a few parts that made it to the final album.

“I find that you can capture little moments on a recorder of any sort,” Gilmour says. “To me, the important thing is being there and capturing it at the moment that it’s formed, that it forms itself in you. Even with an iPhone recording, you can actually use that little bit of recording, and you can embed something of suspect sound quality in a framework, in a setting of higher level recordings, and recorded instruments, and they will all sound like part of the same thing. And that way you don’t have to kill yourself trying to recapture the magic that you sometimes get on your little demos.

“The piano on ‘A Boat Lies Waiting’ that we talked about was recorded on a minidisc–that’s how long ago it was!–but there are also some pieces on the album that I began on my iPhone,” Gilmour continues. “Nowadays I find that you can actually keep and use those things. The perverse way that life works, the moment that a great idea comes on you could be when you’re in the taxi from the hotel to the gig, or you’re in the dressing room, or somewhere else, or having a pee. You can never quite tell at what point these things are going to manifest themselves. But if you can just whip your iPhone out, turn on the record function and capture it, the little bit of magic that you’re hearing as you’re doing it will be captured too. You can then either use it or recreate it. But if you don’t capture it at the time, you’ll find yourself wondering exactly what that magic was.”

Gilmour is also lucky in that his key songwriting collaborator is close by. His wife Polly Samson–whom I profiled for Quartz last month–has written lyrics for Gilmour’s music since The Division Bell days.

“The idea of my name being attached to Pink Floyd was like some nightmare,” Polly Samson tells me of their earliest days working together. “I know this sounds crazy now, but that’s how it felt at the time. I said to him, ‘Look, I’m really happy to be paid for my work, but please leave my name off it. I just would feel so scrutinized.’ Actually, as it turned out, he rather sensibly said, ‘I’m just not prepared to do this. You will have your name on it because you’ve written it.’ Nothing that I said to him could make him change his mind. He said, ‘There will come a time when you will thank me for this, because it’s horrible when you don’t get credit for your own work.’ Actually he was right, and I was right too, because in those days, rather unhelpfully, Roger Waters came out and said something like, ‘How sad, getting the girlfriend to write lyrics.’ When you think about that statement now, he’d be crucified for disqualifying someone on the grounds of their relationship with the person or the fact that they’re female or whatever that was. Then there was the big tour, and I got used to it, really. I got used to David singing words I’d written. The world didn’t collapse and it all seemed to work very well. Then he didn’t do anything I think for quite a long time.”

In 2006, the pair collaborated closely on Gilmour’s album On An Island. It was a huge critical and commercial success. And again, the world didn’t collapse.

“I’ve become very much more confident as a writer and less inhibited with writing lyrics, partly because On An Island was successful, the world didn’t end,” Samson jokes. “Then came The Endless River, which I very much didn’t want to write lyrics for, because Rick was no longer with us and the jamming was so beautiful. It felt wrong for me to impose lyrics. But David wanted a song. He felt that there should be a full stop to Pink Floyd, so that was the only time I’ve written without a piece of music first, because I didn’t want a piece of music. I knew what the subject was, and the subject was very clear to me, as I’d spent time with all of them.

“I remember thinking at Live8 that there’s nothing more excruciating than being in a room with David, Rick, Nick, and Roger,” Samson recalls, with a chuckle. “They do not speak. They have no conversation at all. It’s awkward. You’re with these four men, they do not speak, there are awkward silences, and the next thing is that they’re up on stage and speaking so eloquently through their instruments. There’s this real divide between this incredible articulacy they have with music that they absolutely don’t have in their relationships. That night at Live8 it really struck me, this terrible awkwardness. That sort of summed it up, really, and it was what I wanted to write about. I didn’t have a piece of music. I just wrote that song and said to David that if he had a piece of music for it, it might work. He said he had a piece of music and it was exactly what he wanted to say. So each time, I suppose, I’ve become more confident.

“And of course David is impossible to get to write lyrics!” Samson exclaims. “It’s like a child preparing for exams. He just puts it off and puts it off. He did write a few for this album in the end, but most of it we worked on together.”

“We usually go over to the studio together when we’ve got her first draft of something,” Gilmour tells me of their collaborative process. “I put the mic up and sing it, and we see where to take it from there.”

Phil Manzanera, who most music fans will know from his days playing guitar in Roxy Music, also helped the creative process along immensely, Gilmour tells me.

“He’s always there and helpful, good to bounce things off, always positive and always trying to push things forward,” Gilmour says, fondly. “He’s a great guy to have around. As is Andy Jackson, my engineer, particularly when we’re mixing, and he really takes it all over. The first half or more of the album, two thirds of the album making tends to be me doing everything, because I’m reasonably adept with Pro Tools and engineering stuff. Then Andy comes in and fixes it all. Even if I haven’t made it brilliant myself, he can make it brilliant afterwards. But Phil was there from the beginning. He listened to old pieces of music of mine, found little moments I might have forgotten, and would say, ‘Wait, we could put this piece into there and join that piece with that piece.’ He’s got a very brilliant archival mind. He can remember lots of little pieces of music I’ve long since forgotten. When you’re looking for stuff, he’s brilliant to have around. He’s always brilliant to have around.”

When I point out that it sounds as though Gilmour has surrounded himself with like-minded collaborators who are supportive and drama-averse, his days in Pink Floyd are clearly not far from his mind.

“I don’t know who you’re talking about!” Gilmour exclaims with a hearty laugh.

Gilmour is preparing to tour in support of Rattle That Lock, first in the UK and Europe this fall, and then in the US next spring. When I point out how powerful and clear his voice–the voice so inextricably linked with so many of Pink Floyd’s hits to so many–sounds on the new record, he waves me off.

“I haven’t sort of overused it quite as much in the past few years, maybe that’s what it is, I dunno,” he says. “I’m very pleased with the way it seems to have worked during the making of this album, though.”

As for the tour, Gilmour says he’s only just starting to think about what he’ll play, though his tour to support On An Island saw him digging deep into Pink Floyd’s songbook, playing hits like “Comfortably Numb” and “Wish You Were Here” (“I never tire of playing those. I suppose I should. But I don’t.”), alongside early epics like “Astonomy Domine”.

“I’m about to get to working on the setlist, but I’m afraid I haven’t really started yet,” Gilmour confesses, exhibiting a bit of the schoolkid preparing for exams that Samson alluded to in our conversation. “I literally only finished the album. I next have to turn my view towards what I’m going to do, but I haven’t given it a second thought yet. I just want to do the latest material I’ve been working on and throw in the songs I like the most from a long career. Now, obviously, my view on it is often the same I think the fans want to hear, but I don’t play songs that I don’t like even if the fans do. I’m always trying to make a set that flows and have a logic to it, and also one that works with the audience. Quite how that happens I don’t know. You change it as you go along.”