Plunging oil prices may have people dancing on OPEC’s grave, but geopolitical havoc is the price we’ll pay

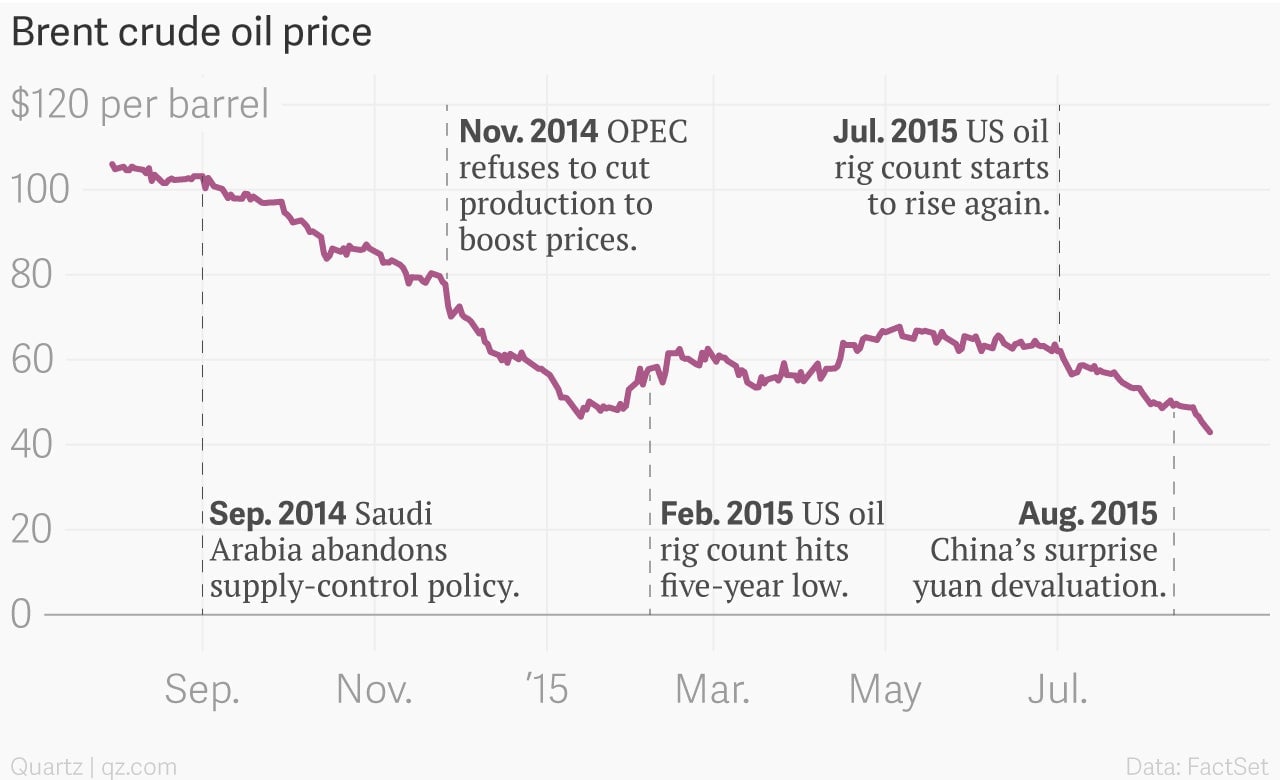

Not too long ago, oil prices seemed to have bottomed out. Internationally traded Brent crude was climbing back toward $70 a barrel after plunging into the mid-$40s, and a lot of analysts were giving the all-clear signal. After the breathtaking plunge from $115 a barrel in June 2014, the oil patch misery seemed to be over, so companies and petro-dictators could go back to business as usual.

Not too long ago, oil prices seemed to have bottomed out. Internationally traded Brent crude was climbing back toward $70 a barrel after plunging into the mid-$40s, and a lot of analysts were giving the all-clear signal. After the breathtaking plunge from $115 a barrel in June 2014, the oil patch misery seemed to be over, so companies and petro-dictators could go back to business as usual.

But, as we reported, a couple of prominent analysts weren’t ready to leave the battlefield. Barclays’ Kevin Norrish warned that we were witnessing a false price recovery, and that Brent was headed back down—it would average $40-$50 a barrel for the year, Norrish said. Citi’s Ed Morse was even more bearish—Brent would fall below $40 a barrel later in the year, he said, and perhaps even to $20.

Today, Brent in fact does appear to be spiraling down toward the symbolic $40-a-barrel price barrier, and perhaps below—its low as of this writing was $42.51 a barrel. WTI, the US-traded grade, traded as low as $37.75 a barrel.

Their rationale holds still—US shale drillers remain resilient despite the earlier belief that their costs were too high to sustain production against low prices; OPEC is producing as much oil as it can in an effort to retain market share; and Iran appears to be on the cusp of throwing even more volume onto the market. Meanwhile, demand is up, but has been trounced by all the supply.

Watching this price plunge, it’s easy to imagine the queasiness in places long unaccustomed to such sensations—OPEC, for example, and Russia, both of them fiscally reliant on oil exports.

There has been a certain amount of schadenfreude: It appeared that after so many decades of outsized influence, the Saudi Arabians and other Gulf giants would suffer a dose of humility. And as for Russia’s president Vladimir Putin, many felt he deserved a comeuppance after the invasion of Ukraine. In fact, the longer low oil prices were sustained, the more humble Putin was likely to be, in line with the First Law of Petropolitics, which states that a petro-dictator’s mood moves in direct relationship to the price of oil—in high times, he is a jerk; and as prices drop, a friendly smile begins to cross his face.

But, as low prices seem likely to extend well into 2016 and even into 2017, a different reality suggests itself—the danger of a wave of new instability in the Middle East as some OPEC nations may find themselves unable to sustain social spending.

Given the turmoil in Syria, Iraq and Yemen, would a Saudi Arabia in chaos be a good thing, especially in the short and medium term? Probably not. As of now, almost no one has predicted that Saudi is headed that direction. But as the oil price plunge in general has shown, consensus forecasting is often wrong.