Before you watch a tragic, graphic news video, ask who wants you to see it, and why

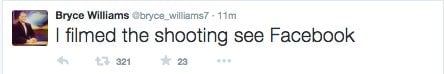

After shooting Alison Parker and Adam Ward dead yesterday morning in Roanoke, Virginia, Vester Flanagan—a.k.a. Bryce Williams—posted a video showing the murder from his vantage point to Facebook and Twitter, and told everyone to look.

After shooting Alison Parker and Adam Ward dead yesterday morning in Roanoke, Virginia, Vester Flanagan—a.k.a. Bryce Williams—posted a video showing the murder from his vantage point to Facebook and Twitter, and told everyone to look.

Facebook and Twitter quickly shut down Flanagan’s accounts. But this being the internet, there are probably copies of the video circulating somewhere. Easier to find, there are also many stills from just before Flanagan started shooting. With Parker and her interviewee a few feet in front of him, Flanagan’s gun hand intrudes into the frame, as if in a first-person-shooter video game.

But I won’t show you that picture, because last summer, after the Islamic State starting posting beheading videos, I wrote that people shouldn’t share or link to them. In sharing, I said, we were playing into ISIL’s hands, serving its desire for publicity.

My point wasn’t to keep graphic images of death from being seen. In some cases, like the then-recent police killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, I thought they should be seen, because they could do good in the world. This is the test I proposed back then for discerning the difference:

Images don’t have agendas. Those who spread them do. When you next are tempted by a link with a self-conscious “WARNING: GRAPHIC” before it, ask not “Is this going to be too gruesome?” but instead “Why do they want me to see it?”

Vester Flanagan is like ISIL. He wanted you to see. Though we don’t know exactly why—and we may never know, since he killed himself shortly afterwards—we do know that he wanted so badly for you to see that he made a video, uploaded it, and told everyone to go look. He didn’t just want to commit murder—he wanted the reward of attention, for having done it.

“The media”—if that term refers to newspapers, TV stations, and news websites such as Quartz—control less and less of what we see. (The very reason the Middle East became so dangerous for journalists is that ISIL no longer needed them to get its message out; instead, in a gruesome twist on McLuhan, the journalists became the message.) Today the whole internet is the media—or rather, as befits this bigger entity, the Media—and everyone who uses the internet is a member of the Media.

In terms of influence and credibility, there are no clear distinctions between members of the media and members of the Media; there are only sliding scales. A savvy user of Twitter, YouTube or Instagram can gain a following in the Media that puts many members of the media to shame. By posting his kill video to Facebook, Flanagan/Williams, a former reporter at the TV station where his victims worked, probably had much greater impact as a member of the Media than he ever did working for the media.

As members of the Media, every one of us faces ethical dilemmas that employees of the media deal with almost daily. What effect do we have when we spread information that seems important but might be false? And whose interests do we serve when we link to a video designed to get attention for a gruesome act, or even to a still photo from that video?

You may think it doesn’t matter; you’re only circulating it to a few (or a few hundred) of your closest friends. But collectively, our decisions to share or not to share can have more impact than those of the world’s biggest media networks.

You might say this is a dilemma not for you, but for the technology platforms, such as Twitter and YouTube, to face. After all, they are the infrastructure of the Media. They have whole teams of people to think about this kind of thing. They already have great power to prevent images of carnage from circulating, and as their image-recognition algorithms get better, that power is growing.

But it is not obvious that they should wield that power. Last week there was great disquiet when Twitter decided that politicians who deleted embarrassing tweets had the right to not have those tweets resurface on other platforms. At the tweak of a setting in its API, Twitter handed them a tool of censorship. A politician cannot make the media unprint his faux pas, but he can make it disappear from the Media with a single click. So if we shrug and say that it’s up to Facebook’s algorithms to control the spread of Flanagan’s video, we hand Facebook the power to control a great many other things too.

Some have argued with me that Flanagan’s video is not like the video of ISIL beheading James Foley; rather, it is like the video of police strangling Eric Garner to death, in that watching it will serve a social good. We should watch Flanagan’s video, they say, to make us confront the damage that easy access to guns can do.

But I’m not so sure that will change anything.

We will see more Vester Flanagans. The first-person-shooter—now in both senses of “shooter”—is a new Media form, and new forms attract innovators and copycats. There will be other new forms, too. How long before a murderer mounts a GoPro on his rifle or films his act from multiple angles using drone-cams to give it the full Hollywood treatment?

The murderous creators who work in these new forms will make calculated and increasingly spectacular bids for attention. They know that you, as Media consumer, will click hungrily on any innovation, and as Media member, will spread it to your shocked but fascinated friends.

Ultimately, then, it’s down to your conscience. You are not a helpless witness to violence—you are a member of the Media. Understand that power. What do you want to do with it?