Life after web content blocking becomes official

Ad blocking started as an initiative by independent developers who wanted to improve our browsing experience. Now that at least one company, Apple, has made Content Blocking “official,” ad-supported publishing business models are in trouble.

Ad blocking started as an initiative by independent developers who wanted to improve our browsing experience. Now that at least one company, Apple, has made Content Blocking “official,” ad-supported publishing business models are in trouble.

Back in the days when we bought a newspaper or magazine at the newsstand, we thought we were paying for the newspaper. We were only faintly aware that advertising contributed a large share of the paper’s revenue. In some cases, like old computer magazines, ads were welcomed and even avidly sought by the reader; they provided a needed source of information in a rapidly evolving field.

No strings attached—we buy, we read, and we’re done.

Then, the Web happened and newspapers and magazines became available online. The unlimited number of sources of information and entertainment has lead to a new kind of tragedy of the commons: When finite advertising budgets are divided by an almost infinite number of Internet billboards, the revenue per ad tends to zero. As revenue from print ads continues to decline, Web ads aren’t picking up the slack:

We now have a race to the bottom where publishers use tricks (some say fraud) to generate advertising revenue. This leads to pages that are overloaded with ads that publishers no longer control, combined with the collection of the most minute crevices of user behavior, information that’s then pimped to advertisers who are constantly looking for more finely-tuned methods to target their ads.

Ad blocking technology—browser modules that could detect and block ads—emerged as a way to combat some of these abuses. Unavoidably, this led to cat and mouse games. As detection improved, advertisers learned to sniff the rules and avoid the blocks. It also led to whitelisting, a “feature” that I can’t but call an extortion racket. Adblock Plus from Eyeo GmbH maintains a whitelist of the “good guys”—advertisers who pay to be let through the gates. Large companies such as Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Taboola pay AdBlock Plus to lift the ad barrier. Lovely, especially for small, marginally profitable companies who can’t afford the bribe.

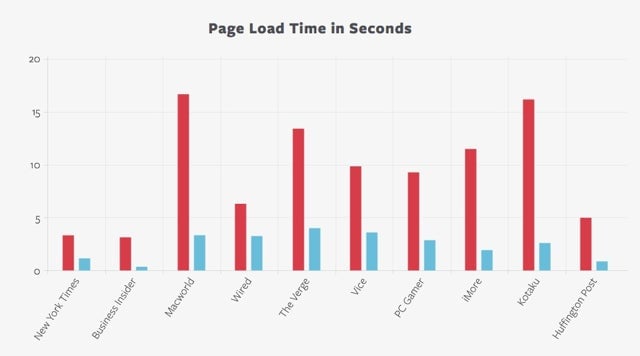

We’re now about to have a cleaner set of content blocking APIs in upcoming versions of Safari for OS X (desktop) and iOS 9 (mobile). These APIs will allow app developers, Apple included, to create a range of blocking tools aimed at removing or filtering ads and improving privacy. An early example is Crystal by Dean Murphy, which demonstrates marked improvements in page load times and sizes:

(TechCrunch provides a detailed overview of the content blocking wave).

The good news: We’ll soon have ways to streamline our browsing experience and avoid being pimped to advertisers.

The bad news: Marginally profitable websites, which is most of them, will lose advertising revenue and plunge into the red. The big guys that have paywalls in place—sites such as The New York Times, Financial Times, or Le Monde—will be much less vulnerable. (More on the Web publishing landscape in the postscript.)

What are the smaller publishers to do?

Displaying their outrage by posting “Access Denied” when reached by an “offending” browser won’t work.

Some very specialized sites, such as Ben Thompson’s Stratechery and Ben Bajarin’s TechPinions, are able to generate membership revenue because the quality of their content—sober analysis versus mere reporting—makes it worth the price of subscription.

But these are exceptions. Too many sites are just echo chambers, they rewrite news releases, add strong adjectives and adverbs, and a bit of spin. Competition for attention, pageviews, and advertising dollars drives them to shout from the rooftops. If they don’t want to disappear or be rolled up into a larger entity to “optimize expenses,” they’ll have to get us to pay for their content.

This is much easier said than done. It’s difficult to conjure up a picture in which we’ll have subscriptions to most of the sites we graze today in their ad-supported form.

An alternative to subscriptions for content we may or may not actually “consume” is pay-as-you-go. In principle, this isn’t very different from what we do when we buy an episode of Breaking Bad. We gladly pay $2.99 to watch what we want, when we want, and without ads.

This works well for TV shows, but it doesn’t easily translate to websites.

First, we’re not going to pay $2.99 for an article on The Huffington Post. We’ll only pay a small fraction, 1/100th perhaps, of the price of a TV episode.

Second, once we start paying for articles, even in tiny sums, we’ll become much more selective. Irrespective of the amount, the move from free to paid will influence our choices. For many sites, crossing that chasm might prove impossible.

Third and perhaps most important: How will these purchases be transacted? A separate account for each site is impossible. For this to work, we’d have to be registered in a single location from which we could browse, buy, and read. That location would log transactions, count the money, take funds from our credit card or bank account, pay content suppliers on a weekly basis… and keep a percentage for its services.

Sounds familiar? In 2003 Apple opened the iTunes Store with two innovations: Content by the slice and micro-payments; selling music one song at a time for 99 cents.

For a brief dreamy moment, similar arrangement for websites might sound attractive, but the cold reality is that there’s no practical way to put so many websites under one umbrella—Apple’s or anyone else’s—and the business of collecting pennies doesn’t seem viable.

(Apple’s iOS 9 News app is coming. It looks like a clean and well-lighted place for news consumption. It’s too early to weigh its impact, but I don’t think it’ll do much to help ad-supported echo chambers.)

In a previous Monday Note, Frédéric Filloux discussed what he called Ad Block’s doomsday scenarios. This was prophetic: We didn’t know yet about Apple’s addition of content blocking technology to OS X and iOS. Ad blocking is now moving from third party initiatives to a broad assault based on platform technology. This is going to be painful for those whose ad-supported business model is in danger of breaking. There will be blood.

PS: A few thoughts on the Web publishing investment landscape

Some high-quality sites, such as Om Malik’s GigaOM, have folded, while others have been rolled up into larger entities. The Huffington Post was acquired by AoL; Re/Code (née All Things D) was absorbed by Vox Media, which is now partly owned (a $200 million investment) by NBC Universal, itself a part of the Comcast empire. NBC/Comcast just made a $200 million investment in BuzzFeed.

Other media organizations have found individuals of substantial means to buy a large stake in the company, or acquire it outright. Jeff Bezos now owns the Washington Post, and also made “a significant investment” in Business Insider (whose Wikipedia page makes no mention of Bezos). The New York Times’ largest shareholder is Mexican magnate Carlos Slim, the second richest person in the world.

Similar moves have taken place in Europe. Bernard Arnault, the billionaire head of the luxury goods LVMH conglomerate, owns two newspapers: French business daily Les Echos, and Le Parisien. Not to be outdone, billionaires Xavier Niel and Pierre Bergé, joined by investment banker Mathieu Pigasse, are heavily invested in Le Monde. And cable operator magnate Patrick Drahi now owns l’Express and a substantial stake in Libération. None of these French newspapers are in good financial health.

This is puzzling. Newspapers are in trouble due to the never-ending fall in ad revenue—that’s why they get acquired by larger entities or must find a rich investor. But what do these benefactors see in properties that depend on troubled web advertising business models? Do they really believe they’ll make money with these newspapers, perhaps with monopoly profits if they manage to win the last-man-standing game? Or, more disturbingly, do they want to influence the news?

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.