Is Xi Jinping living up to the legacy of China’s greatest modern reformer?

In China, the political meaning of a parade far surpasses a show of military might. It’s a crowning ceremony to justify a leader’s paramount power in the Party. To the world, it is meant to demonstrate national unity and prowess.

In China, the political meaning of a parade far surpasses a show of military might. It’s a crowning ceremony to justify a leader’s paramount power in the Party. To the world, it is meant to demonstrate national unity and prowess.

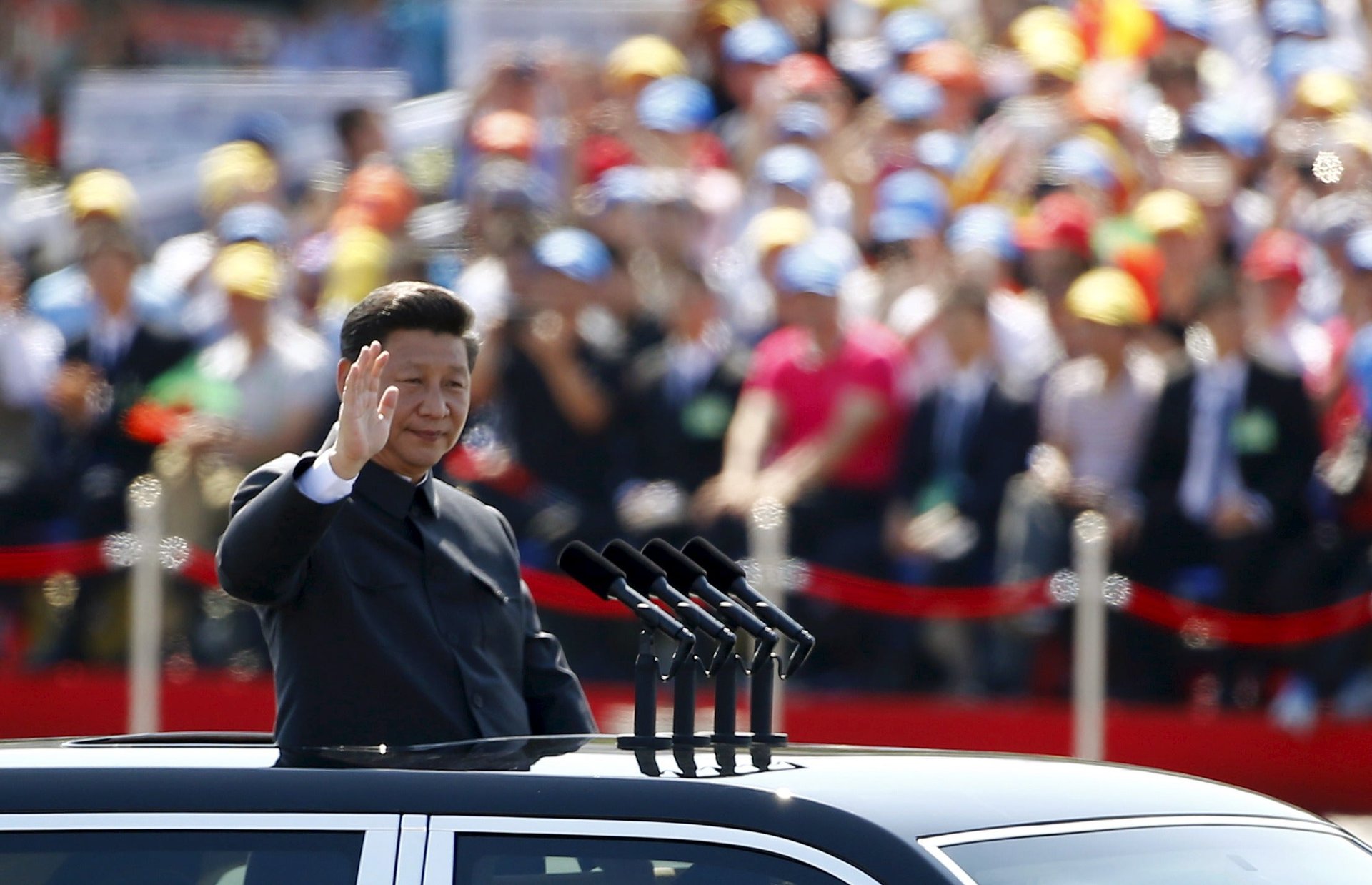

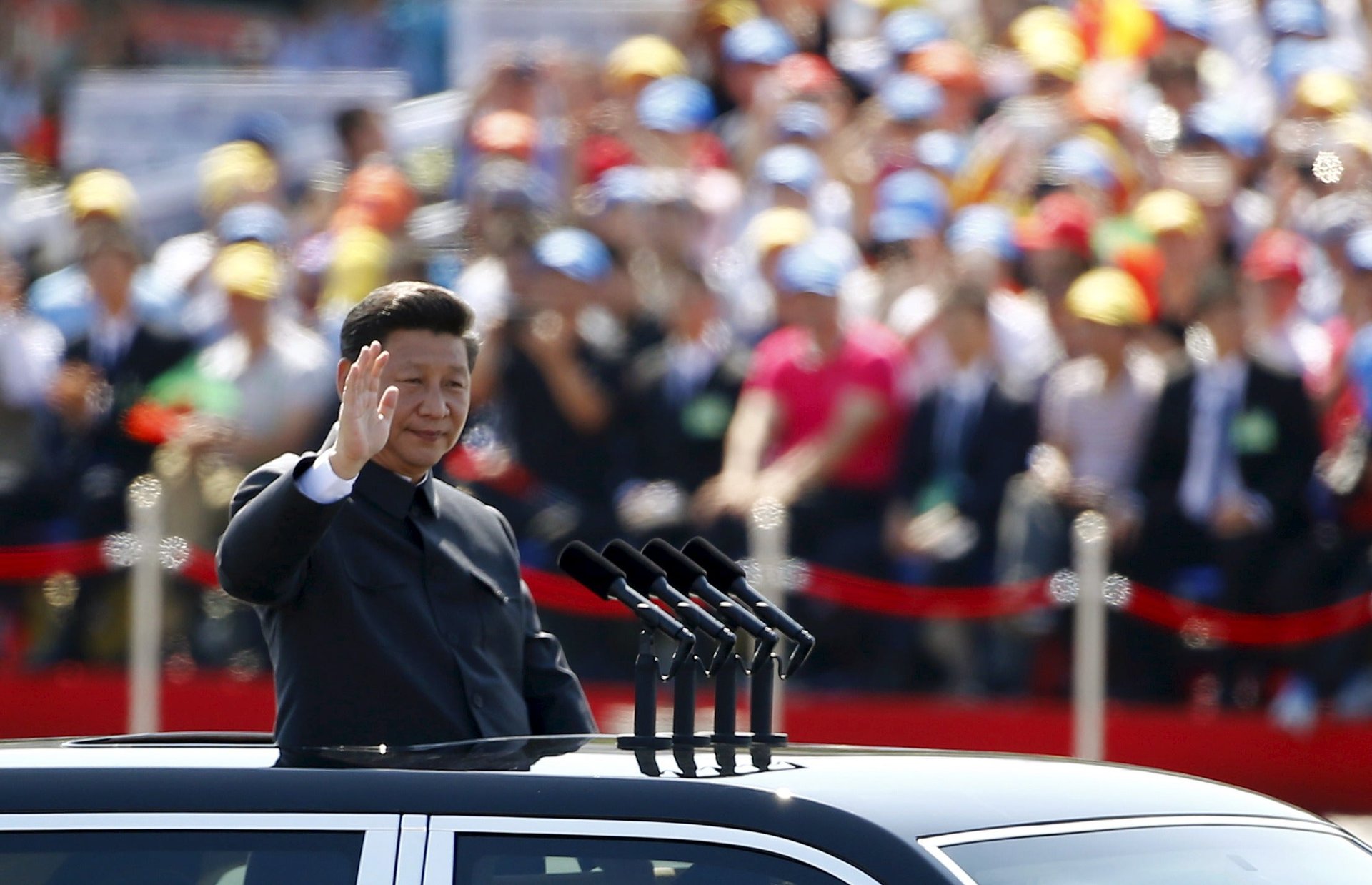

Last week, Chinese President Xi Jinping held China’s first non-National Day military parade ever. More than 30 years ago, in 1984, China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping held a unique parade at the end of the Cultural Revolution, signaling he had reached new heights of power.

The 1984 Parade, the first after Chairman Mao Zedong’s last National Day parade in 1959, was held on Oct.1 to celebrate the 35th National Day. There were 10,370 troops, including 42 ground fractions and 4 air fractions. A group of Peking University students raised a banner made from a bedsheet with “Hello Xiaoping” to celebrate the strong leader’s efforts to transform the country from Mao’s legacy of poverty and dictatorship. As former Beijing-based correspondent Ian Johnson wrote, “At this point Deng and the government were popular for having unshackled China and given people the first taste of prosperity in decades.”

Thirty-one years later, the question is often being asked—is Xi another Deng? The People’s Daily, the ruling Communist Party’s leading mouthpiece, lauded Xi last year with the title of the “new architect” of China’s reform, a term easily associated with Deng’s title of “chief architect.”

Xi certainly holds many new records right after taking China’s helm, like the leader who has the political titles, including heading “comprehensively deepening reform” and “Internet security.” He appears to be trying to compete with Deng by consolidating power, showing diplomacy and making economic reforms, and last week’s parade was a good way to reinforce his strength. But, Xi’s approach in these three areas has often differed radically from Deng’s, and has had very different results.

Why military cuts matter

He even mirrored Deng in announcing layoffs. After reinforcing army’s the duties to safeguard security and peace, Xi, standing on the Tian’anmen Gatetower, announced that the army will lay off 300,000 soldiers before he reviewed troops.

One month after the 1984 parade, Deng launched a disarmament process in the central military committee meeting. In the following three years, the military reduced personnel by 1 million troops. Deng felt the army was costing too much money, was inefficient and was hard to govern.

For Deng, this signaled the start of a new series of reforms to shake off poverty and ensure national security. China has only reduced the size of the military 11 times since 1949 (including Xi’s announcement, and Mao accounted for five of these times). Over that time, China’s troops have been reduced from 6.27 million to only 2.3 million. Scaling down the military usually coincides with domestic economic or social reforms, or happens is response to changes outside China.

So is Xi’s announcement a signal more reform is ahead? Just two days ahead of the parade, the People’s Daily reprinted (link in Chinese) Xi’s talk during an important meeting on Dec. 23, 2013 on the pressure on the military to reform when developed countries made changes.

“Whoever is thinking conservatively, will miss valuable opportunities and will be strategically passive.” Xi said, “Now there’s a good opportunity to deepen national defense and reform the military. We must seize it.”

Consolidating power

Deng was so powerful that it is difficult for anyone, even Xi, to follow in his footsteps, much less overtake him. His political authority was acknowledged without any official inauguration or equivalent ceremonies. When Deng saluted the cheering crowds in the 1984 parade, he was the first leader that had only headed the army, but did not also head the Party and national leadership (At the time, Hu Yaobang was the head of Party and Zhao Ziyang acted as the prime minister).

For either Xi or Deng to throw such a big parade takes deep-rooted support from both the Party and the army.

For Deng, intensive military experience from the 1920s through the civil war with Kuo Ming Tang had gained him many loyalists. Many of his followers were promoted to high-rank positions in the army. Half of the 17 commissioned generals in 1987 were from his previous military division, as Ezra F. Vogel writes in Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China.

At that time, what Deng needed was support from the army to carry out his opening and reform policy. In 1977, a year after the Cultural Revolution ended, an “internal reference report” (link in Chinese) indicated around one-third of the cadets in China’s college for military leaders still supported Mao’s campaign. To promote reform, Deng ordered the army to “test truth by practice” instead of blindly following leaders’ instructions.

Xi, on the other hand, has gathered his power over the Party and the army with swift and widespread anti-graft actions. Since he took office at the Party’s 18th congress in Nov. 2012, more than 100 corrupt officials at provincial/ministerial levels or above have stepped down. Among them, 33 (link in Chinese) are high-level military leaders. Top officials like fallen security czar Zhou Yongkang and general Xu Caihou, who are allegedly loyal to China’s former top leader Jiang Zeming, ended their careers (and in Xu’s case, their life) in disgrace.

Here, Xi appears to have learned from his predecessor Hu Jingtao’s mistakes. Hu’s lack of military prestige forced him to concede the top post to Jiang in his first term. Xi is aware of that, so he has brought top officials from five military regions to the central committee. But beyond that he continues to consolidate power—soon after the 18th Congress, he named only one general, rather than many (the commander of the 2nd Artillery Force) a signal he was rewarding his loyal follower (link in Chinese).

Xi’s anti-corruption actions broke an unwritten rule that has governed the upper echelons of China’s leadership for decades: If you are a member of Politburo, you won’t be charged with any crime, and if you enter the standing committee, your life is protected guaranteed.

Xi’s actions against Zhou Yongkang and Xu Caihou, from sending them to jail to exposing their Party and military violations after they retired, broke a rule that is long held since the Cultural Revolution.

And here’s the paradox—officials of all ranks are now careful about what they do, so are not motivated to be bold and creative for fear that they may attract unwanted attention. Some regional leaders seem to be following a new unwritten rule— “No achievement and no mistakes will ensure your safety”. Some officials who are expected to be pioneers are slow in their actions and thoughts, casting a shadow over lagged economic reforms.

A new foreign relations policy

Last week, Xi’s parade featured 12,000 Chinese troops and more than 500 pieces of weaponry, designed to “shock and awe.” But from a geo-political point of view, the event highlighted weakness in China’s foreign policy instead.

No leaders from major WWII allies, including the US, UK or France attended. Instead, China hosted foreign leaders from Russia and less powerful countries— allowing Xi to assertively showed China’s alliance with Russia and other countries who are “true friends” with China. He missed an opportunity to strengthen relationships with western countries and convince them of China’s views on WWII, and relied on propaganda instead to broadcast his message. After Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe refused to attend, for example, the People’s Daily criticized Tokyo for “challenging the postwar order.”

Taking a proactive stance is Xi’s “new normal” in international relations. It is a grand strategy, one that appears to have based itself somewhat on Deng’s own strategy, which was shaped by his war experiences.

Xi is trying to distinguish himself from Hu’s peaceful rising policy by establishing a new “Big Country Diplomacy.” The plan is to remind foreign countries: China will resume its central position in the way the ancient empire led the world. Threatening measures like the East China Sea ADIZ and South China Sea land reclamation are fueling neighboring countries’ uneasiness. At the same time, China it trying to emphasize the mutual benefits countries can reap by partnering up with its “One Belt, One Road” initiatives and Asia Development Bank plan. In the Party’s propaganda, this is a part of “China Dream.”

Deng also emphasized China’s sovereignty and his strong leadership. With the 1984 parade, Deng was demonstrating national cohesion to the British as they initialed an agreement in September and ahead of the formal Sino-British Joint Declaration in December to end Britain’s over 150 years’ colonization of Hong Kong.

One anecdote from the talks between Deng and British prime minister Margaret Thatcher is well known in China, and used to illustrate how tough Deng had been: in a 1982 meeting, Deng famously stressed that China must have governance over Hong Kong and insisted “Territorial issues bear no negotiation.” After the meeting ended, Thatcher walked out with a hard look on her face, then suddenly tripped in her high heels and fell, dropping her handbag. Many joked that Deng was so tough that he took down the “Iron Lady.”

Though he took a tough stand in Sino-British negotiations, Deng’s lasting foreign policy legacy may be the “hide and bide” approach he adopted. In his mind, stability and peace were the foundation for reform, and he said that China should:

Observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.

To forge amity with the Soviet Union, Vietnam and Taiwan, he reduced China’s military regions from 11 to 7, combining Xinjiang and Lanzhou Military Region and three others (link in Chinese).

Also, he pushed China to normalize relations with the US and the Soviet Union. Following border conflicts with Vietnam, he visited the US, Thailand and others in 1978, finally dampening Vietnam’s pursuit of hegemony in Asia. And China even began a “honeymoon” with Japan. With Deng’s support Party leader Hu Yaobang invited 3,000 youths from Japan to visit, and promised that “China and Japan will be friends generation after generation.”

Japan in turn invited 3,000 Chinese youths to visit, and offered China a 470 billion yen construction loan.

During last week’s speech, Xi promised that “China will never seek hegemony or expansion,” echoing Deng’s strategy. Recently, China has made progress in promoting prosperity and peace, including enhanced international security cooperation with the US, announcing a “good neighbor policy,”and a China-Japan “Four-Point Consensus”. But Xi’s proactive “Big Country” foreign policy has often seemed to contradict these moves.

There are more questions looming for Xi, including Japan’s inconsistent political stances, US trade conflicts, Southeast Asia territorial disputes, terrorist threats near Xinjiang and instability in Tibet.

Tackling the economy

Both Xi and Deng set ambitious public goals to liberalize China’s economy.

In the 1984 parade speech Deng said that China’s major task was to systemically reform the current economic system. He pledged to “quadruple China’s GDP of 1980 by 2000” during the 12th Party’s Congress. He visited the US and Japan, gathered experts in China for advanced theories, and tackled the GDP goal with a three-step strategy. All of his plans were focused on dismantling the legacy of Mao’s impoverished economy and dictatorship.

Deng used his parade to display his commitment to economic reform. Two reformers, Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, who would lead the party and government respectively stood during the parade on Tiananmen Gatetower, signaling to conservatives and liberal intellectuals they should follow his route. Later, both of them were ruled out of future leadership because they showed mercy to demonstrators and failed to halt two influential students protests. One was the 1986 student protest, and the other the Tiananmen Square Protests of 1989. Both called for a democratic government.

Xi’s ambitions have been larger than his predecessors Hu and Jiang. After he took power, the Communist Party highlighted an economic reform agenda that was said to be the most significant since Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 “Southern Tour”. But two years later, it seems to have lagged somewhat.

This year, the 2016-2020 plan came out in May, promised to give markets a “decisive role” in resource allocation and “perfect a mixed public-private economy”. Xi held meetings with officials of at least 18 provinces in three months to discuss reform, especially in rural areas where it is necessary to wipe out poverty to build a moderately prosperous society in 2020 as planned.

Xi’s parade may also indicate his willingness to deepen lagged economic reform. But the recent market crash has raised questions about the sophistication of Xi’s knowledge of financial markets and how committed he truly is to “opening up.” What’s for certain is that when China closed the stock market for 113 hours for the parade, many joked it brought a “global sigh of relief.”

Xi’s 2015 is not easy. China has rattled the world with its faltering economy, which is now worse than it appeared during the 2008 financial crisis. The IMF estimates China’s GDP growth will slip grow below 7 percent in 2015. The country’s manufacturing and service sector is shrinking, and the Caixin/Markit purchasing managers’ index slipped to 47.3 in August, a six year low.

Numerous new challenges like a labor shortage and an aging population are also weighing on China. But what’s more crucial is that the delay of political reform and aggregation of decision-making power leaves Xi fewer options and could worsen the outlook. Xi’s approach to economic reform is rapid, personalized, top-level decision making and presenting a comprehensive reform agenda with a strong political backing. But until now, most of Xi’s economic reform promises are still promises.

The government failed to enable the market to regulate itself and efficiently open up more economy sectors to private firms, so it is tough to stimulate the economy.

In terms of all three aspects we compared, Xi, at least right now, is not as powerful as Deng. The analogy may be a bit unfair to Xi, who has had less time in power so far, and surely has many years ahead to firm up his strategy. Standing top of a more developed China, however, Xi doesn’t have the same golden opportunities that Deng did. It is starting to seem like Xi can mirror his strong predecessor’s posture, but the world is waiting to see more of his strategic insight.

Wendy Zhou is a research assistant at a Hong Kong-based university with a masters in journalism.