Why Europe is so wary of US tech giants

Two weeks ago, we looked at the motives underlying Europe’s frustration vis-à-vis internet giants. To sum up: desktop and mobile traffic completely captured by the likes of Google, Microsoft and Facebook; anemic access to venture capital and smaller expenditures per student, especially in tertiary education.

Two weeks ago, we looked at the motives underlying Europe’s frustration vis-à-vis internet giants. To sum up: desktop and mobile traffic completely captured by the likes of Google, Microsoft and Facebook; anemic access to venture capital and smaller expenditures per student, especially in tertiary education.

Today we’ll dive into what is genuinely an ideology. All ingredients are present: a clearly identified enemy, facile but nebulous amalgamation, a charismatic crusader supported by a quasi political organization.

Here in Europe, the enemy is designated by acronyms. A year ago it was GAFA, for Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple. This summer, a new, trendier one, emerged: NATU, for Netflix, Airbnb, Tesla, and Uber. (No one has had yet the idea of merging the two, probably to avoid a name sounding like a Polynesian archipelago.)

These two concepts are mostly European, especially German and French, but they have been effectively promoted in Brussels which always enjoys simple, easy communicable ideas. When you mention GAFA elsewhere, in the United States or Asia, no one sees what you’re referring to (NATU is too recent to even be noted). The concept doesn’t enjoy any traction in UK or Scandinavia either.

These eight companies aggregate all the attributes of insolent capitalism: meteoric rise; large market shares—that could only be the result of predatory practices; staggering valuations; disrespect for old models and for the well-being of brave workers who toil inside those ogres. This indeed makes great ammunition for media artillery.

When looking more closely, however, the GAFA+NATU concepts are deeply flawed.

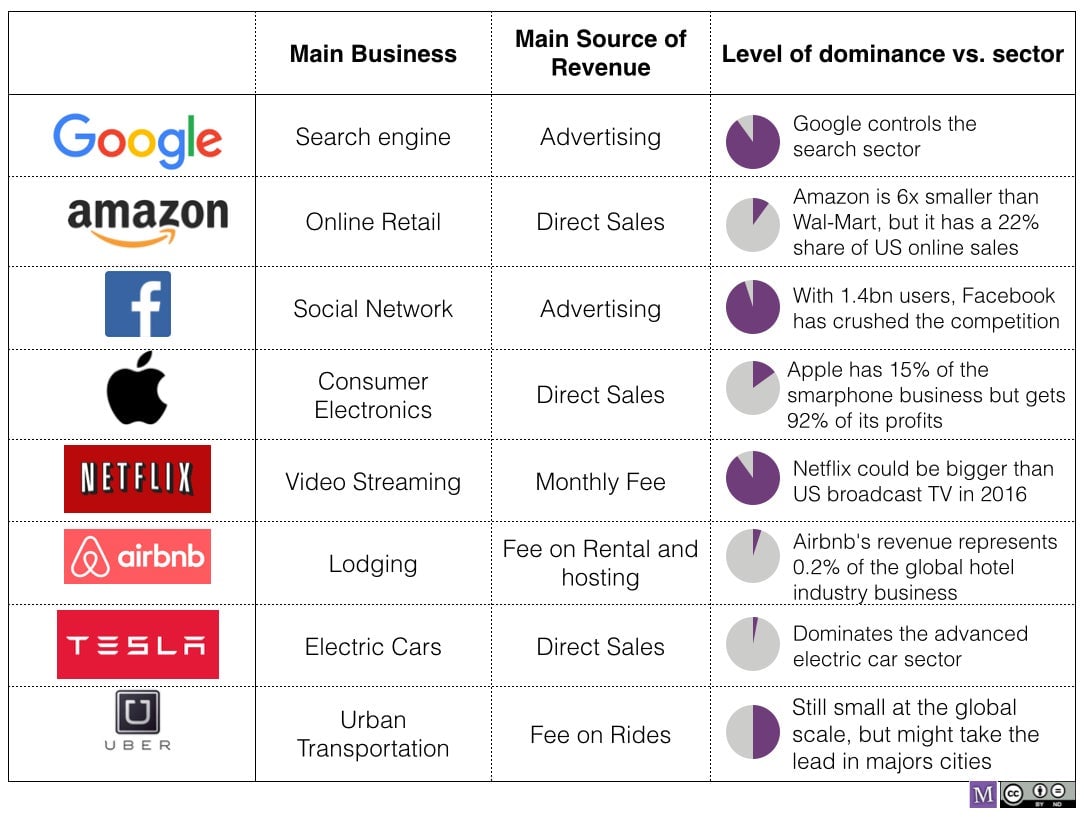

In the table below, I mapped out the sectors and sources of revenue, Then, I gave a shot at assessing their real or fantasized dominance—not on their niche market but on their industry as a whole.

First, they operate in a vast array of sectors. Some are aging, begging for a shakeout: the taxi industry, disrupted by Uber; the lodging sector (Airbnb); and the car industry with Tesla, now only a speck on the windshield. Others sectors are new, and those who seem to have taken over have actually created them: Apple invented the smartphone (and the tablet); Facebook coined the concept of social network. As for the search sector, considered in the broadest sense, Google didn’t create it. Dozens of players tried since 1993. But, in the early days, search was mostly based on full-text retrieval and directories. Google took over this business thanks to a revolutionary idea: the PageRank algorithm in which web links “vote” on a content’s popularity. This is the innovation that created an entirely new sector.

Second, their business models are as multifaceted as can be, to the point of exhibiting contradictory approaches. Take Amazon and Apple. The retailer sells hardware at a loss (Kindle) to funnel more users to its e-books. Apple, on the other hand, created an entertainment business (music, movies, software) only to sell more hardware at higher margins. Except for Google and Facebook, which are in cutthroat competition for advertising, the revenue models of these eight players are not even distant cousins.

Among these corporations, though, two commonalities emerge. These companies are all built on an obsessive customer culture which percolates both in the user experience and customer service. Whether it is for retail, travel, or urban transportation, just compare the old and the new (Airbnb and Uber’s ease of use, Amazon’s return policy or Tesla’s assistance). They rely heavily on their customer’s data to improve all of the above (you’ll benefit of Amazon’s assistance better if you are rated as a non-cheating customer), and user experience usually evolves through tons of real-time analytics. (On these specifics, I recommend reading “GAFAnomics” a 76 slide study put together by the consulting firm Fabernovel.)

On these two matters —the customer-centric approach and the use of data—the new players induce change: see as an example the evolution of airlines and railway apps over the last two years.

Data collection and use are a matter of serious concern—one in which regulators have indeed a critical role to play. However, we should keep in mind that the data brokerage business is one of the oldest marketing profession. But data-vacuuming and crunching companies such as Acxiom, Datalogix (now owned by Oracle), Epsilon and Experian generate only a fraction of the headlines that Facebook or Google get, even if they are part of a $150 to $180 billion business, three times Facebook and Google combined. (Data brokers are closely watched by the Federal Trade Commission.)

Let’s now come to the most debatable part of our chart: The eight players’ level of dominance. The common, headline-grabbing approach is to consider these companies in the environment they created. Google is the perfect example as it commands up to 95% market share in search, a sector born with the internet. Many tried to dislodge Google, injecting billions in the process (e.g. Microsoft with Bing, and the Europe-funded project Quaero that failed to take off).

Others players suggest a more nuanced view:

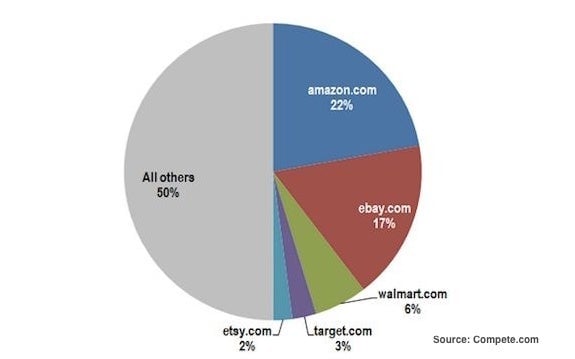

Amazon: It clearly dominates the online retail in the US with 22% of sales:

But it’s far from a monopoly, even in its home market: about 50% of the US online retail is spread among countless players. If we consider the entire US retail market, Amazon is in the 9th position, with worldwide sales six times smaller than Wal-Mart and domestic sales seven times lower, see below:

This Summer’s headlines shouting “Amazon now bigger than Wal-Mart”, based on their respective market capitalization, provides a distorted, eye-catching view of the facts. Amazon has a long way to go to control the retail sector.

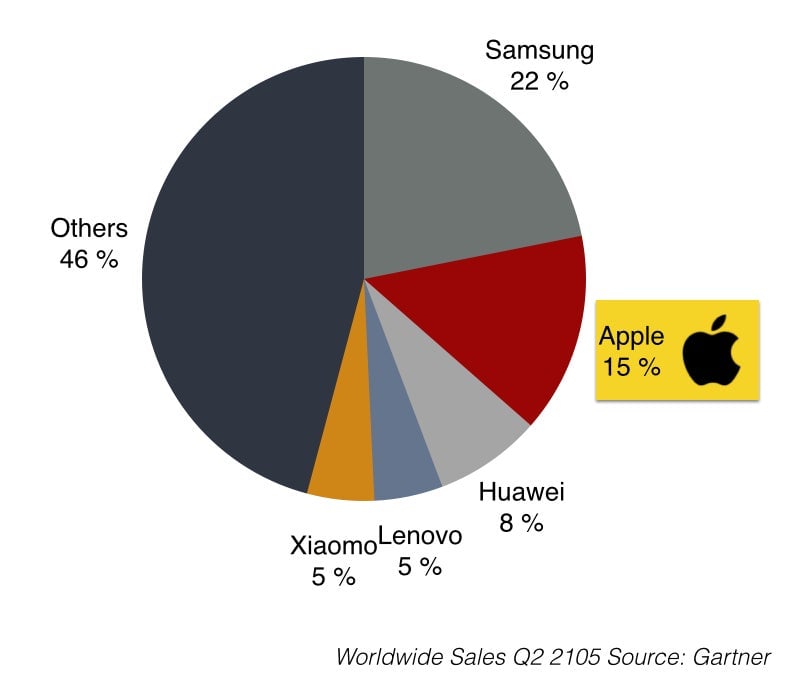

Apple. Its position on the mobile phone: 15% of the worldwide units sales for the second quarter of 2015 according to Gartner:

By viewing this chart, Samsung would deserved to be single out as a tech villain by the European zealots, but again, Samsung is a Korean Company, much less newsworthy than Apple. Especially since Apple is a spectacularly profitable corporation: with the iPhone, it reaps 92% of the phone industry profits, leaving 15% for Samsung; that is 106% of the industry profit for the two players, the rest of the 1000 handset makers barely breaking even or losing money…

Netflix triggered strong fear in Europe, but it failed (so far) to get a meaningful market share. Its position in the the US television market is not easy to estimate since its measurement by Nielsen is unreliable (as are most of Nielsen data). But, according to Variety:

If Netflix were a Nielsen-rated TV network, the No. 1 streaming service would, within a year, attain a larger 24-hour audience than each of the major broadcast networks—ABC, CBS, Fox and NBC—according to the Wall Street analyst firm FBR Capital Markets.

Netflix’s dominance mostly relies on its incredible recommendation system operated by 300 persons vs. few dozens here and there in Europe’s VOD companies. The investment paid off in spectacular fashion.

In Airbnb’s case, eyeballs are focused of its staggering valuation—$24 billion vs. $21 billion for Marriott, which operates (not the same thing as owning) 4,000 hotels. But its revenue for 2015 is estimated at $850 million, which is about 0.2% of the $450 billion for the entire hotel industry.

But the media machine is working at full throttle here: Airbnb’s visibility, its many local quarrels with municipalities sell more than the performance of Booking.com or Hotels.com, even though these two constitute the biggest threat to the hotel industry by eating into their margin.

Tesla sold 2,000 cars in August, that’s a 0.1% market share of the US market. Not exactly a threat to Detroit. But again,the media magnifier sets in: A highly rated car, envisioned by a charismatic leader—Elon Musk—who is also betting the farm on a “gigafactory” that will change the scale of battery production. Tesla’s trademark: Musk is a pure product of Silicon Valley; he is the co-creator of PayPal, and he approaches his three businesses—Tesla, SpaceX and Solar City—with the same disruptive mentality as his peers in the tech world. Tesla has long way to go to be successful, and it’s likely to remain a niche product.

Uber is the most difficult business to assess. The company is expected to generate $2 billion in revenue this year, which is probably less than 10% of the global taxi industry. But according to its CEO Travis Kalanick, it made $500 million in San Francisco alone, vs. $140 million for the dwindling SF cabs. In New York, Uber now has slightly more registered cars (14,000) than all cabs together. The startup is growing three times per year in SF, four times in NY, five to six times in London. In the long run, it might outrun the local taxi sector in many cities—in Paris, the sooner the better.

That said, justifying its $51 billion valuation won’t be easy. Says Chris Myers, a contributing Forbes analyst:

Uber’s $50 billion valuation means that they will need to generate about $35.7 billion dollars of gross revenue and about $7.1 billion dollars of net revenue to justify the recent valuation. Perhaps more interestingly, the company will have to have an annual growth rate of about 286% each year over the next five years to hit these numbers.

When looking at hard facts and taking a bird’s eye view, the presumed crushing domination of the GAFA+NATU bandwagon is less obvious than the media storm portrays it. Europe is beset by its weaknesses, failures and many-faceted conservatism. Instead of focusing on remedies—access to capital, higher education, labor laws, innovation stimuli, it builds an ideology around a threatening, foreign-born, domination. In Brussels, the fight is embodied by Margrethe Vestager, the European Commissioner in charge of competition. She is smart, charismatic and bold. Her administrative arm is 900 people strong. Against Google, her mission is supported by the German publishing industry. And the overzealous European media is smelling blood.