Why charisma eludes Germany’s politicians

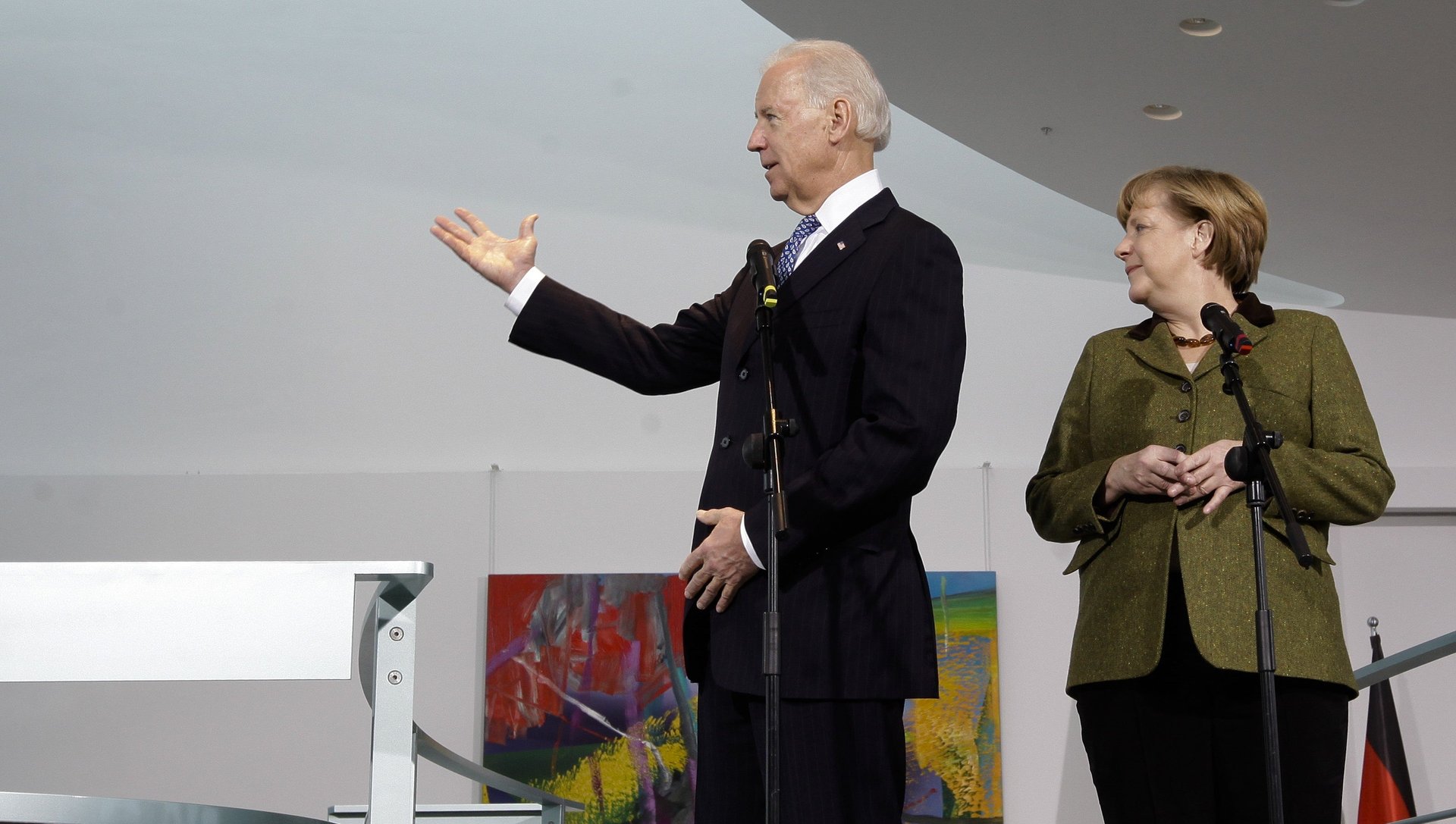

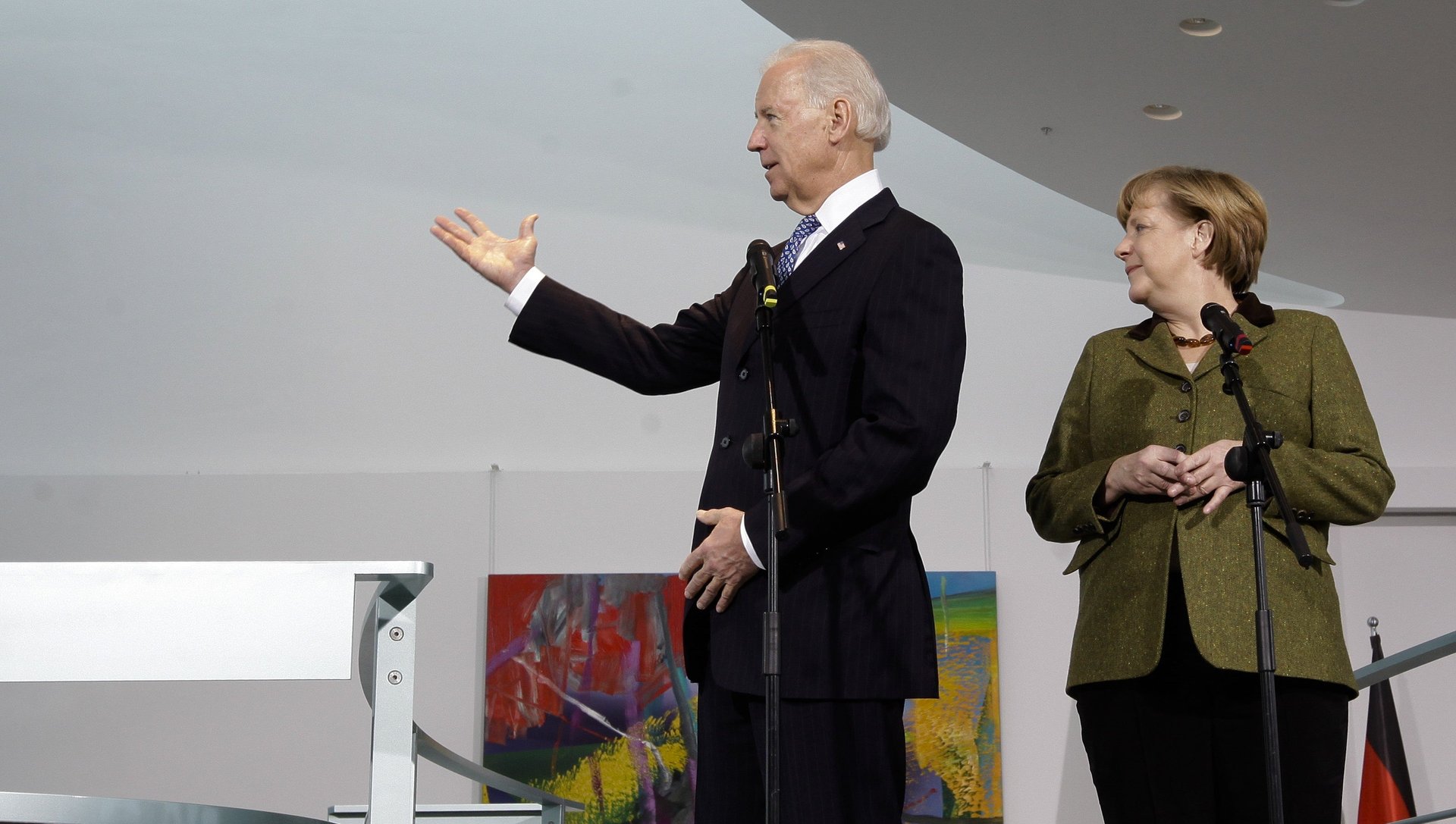

US Vice President Joe Biden was the star of the Munich Security Conference this past weekend. He shook hands, smiled into the cameras, presented his thoughts with wide gestures. Next to him, German politicians seemed downright colorless, even inhibited. Europeans had great expectations from Biden, and it wasn’t only for his assurance that the US remains an important coalition partner. There is a certain fascination with charismatic American politicians such as Biden, especially in Germany.

US Vice President Joe Biden was the star of the Munich Security Conference this past weekend. He shook hands, smiled into the cameras, presented his thoughts with wide gestures. Next to him, German politicians seemed downright colorless, even inhibited. Europeans had great expectations from Biden, and it wasn’t only for his assurance that the US remains an important coalition partner. There is a certain fascination with charismatic American politicians such as Biden, especially in Germany.

More than four years ago, as the world watched a young African-American senator become US president, essayists described a society in search of a “German Obama“ (German). Was there someone, anyone out there, who could steer citizens away from their “Politikverdrossenheit,” a German term for the disenchantment with politics? Voter participation shrank to 72% for the national elections in 2009, the lowest in almost 70 years after World War II, and participation was even lower in many local elections. Dissatisfaction with and mistrust of German politicians contribute to that equation.

Perhaps more telling is the world’s view of Germany’s leaders, as evidenced in WikiLeaks’ diplomatic cables, published in 2009. Foreign minister Guido Westerwelle was described to have an “exuberant personality“ with a lack of political knowledge; Chancellor Angela Merkel was described as “tenacious,“ but also “risk-averse“ and “rarely creative.“

Merkel’s challenger, Peer Steinbrück of the Social Democrats has tried a new way to be creative. Last Saturday, a team of supporters started a blog for him. The supporters refer to the US elections as well as the Arab Spring as role models for their new strategy—although critics say that’s a stretch. Steinbrueck’s supporters want to communicate with possible voters “more directly,” making better use of the web. Steinbrueck challenged Merkel to have two televised debates this autumn, just as the “(US) president and the applicant” had. Merkel has refused to do more than one “TV duel,” and Steinbrueck’s supporters have criticized her as “afraid.” Social media users in the meantime wonder why Steinbrueck’s blog doesn’t name its financial supporters, even as it claims to be more direct and transparent. They also say Steinbrueck’s statements about Merkel benefiting from being a woman hardly exude charisma, too.

Once, Germany’s desire for charisma stopped at one politician: Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, the young and wealthy aristocrat who brought change to the ever-complaining politicians in the German Bundestag. His popularity surprised many, including himself. He was seen as a possible Merkel challenger. However, he left his position as minister of defense in 2011 after revelations that he plagiarized his PhD thesis. Still, many were disappointed to see him go, including Merkel, just as it seemed Germans had started trusting their politicians again.

Though she is often criticized for her deficient rhetoric, Merkel’s popularity remains strong. That is in part because Germany’s well-being in the crisis is attributed to her doggedness, and in part because political opponents keep sabotaging themselves amid scandal. The German chancellor clearly has a winning strategy. Namely, Merkel is modest. Some say boring, but unlike US politicians, she doesn’t make great promises. Germans are not very forgiving of broken promises. When former chancellor Gerhard Schroeder failed to restore jobs for at least half of Germany’s unemployed, as he promised, he wasn’t reelected.

Biden last came to the Munich Security Conference, held annually to discuss international security policy, four years ago on “behalf of a new administration,” that pledged to close Guantanamo, double the share of renewable energies in the US, get tough on torture. Obama got reelected without keeping these promises, but making good on others, such as his signature healthcare plan.

Merkel is not the type of leader to push great reforms she thinks are important—unless demanded by the German public. She is reacting rather than self-starting. One example was Germany’s outcry over the Fukushima disaster that led to a sudden decision to abandon the country’s nuclear power plants. This strategy keeps voter trust and helps Merkel to stay in power. She has learned from her predecessors not to make promises she can’t keep. That has given her the image of a reliable and trustworthy politician, but hardly bold or visionary.

Perhaps what keeps Germany from having more charismatic, engaging politicians is that the idea of a bold, powerful leader is not very welcome either. Former chancellor Helmut Schmidt described Obama as charismatic leader, in the vein of Hitler and Stalin. Indeed, a strong, monarch-like leader conjures a painful past for Germans, and the same sentiment makes it hard right now for the country to take a leading position in the European crisis. Parties also are careful with candidates that break ranks—Steinbrück is under a close watch now, as well as Rainer Brüderle from the Free Democrats, currently embroiled in a debate over sexism. Werner A. Perger, reporter at Zeit Online, questions how someone like Obama even would stand a chance in the German party landscape (German).

Germans indeed both admire and criticize the political discussion in the US, watching it all unfold much as they might take in a movie or TV show. They like the hard-fought presidential TV debates, they like to see Obama’s tears over the Newton school massacre, they like how US politics has a larger scope than its German counterpart, which tends to get lost in bureaucratic details. But they also feel uncomfortable with US self-adulation; German politicians would never refer to Germany as being the greatest country in the world. In that sense, they might prefer a more modest figure, like an Angela Merkel.

Despite what they say, maybe Germans don’t want a replica of Obama or Biden. Maybe they would like their politicians to just be a little more courageous and visionary. But that would also mean Germans have to learn to be a bit more forgiving.