Janet Yellen is kind of like the Pope of money, and she needs a miracle

Pope Francis’ address to the US Congress today is eating up most of the media bandwidth. But for the US economy, a far more important speech will be delivered later this afternoon at the University of Massachusetts Amherst by Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen.

Pope Francis’ address to the US Congress today is eating up most of the media bandwidth. But for the US economy, a far more important speech will be delivered later this afternoon at the University of Massachusetts Amherst by Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen.

While that may sound like something of a non sequitur, its not too much of a stretch to find some sort of a link between the structure of the Catholic church and the world’s most powerful central bank. In William Greider’s terrific and under-appreciated book on the Fed, Secrets of the Temple, a former official from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston had this to say.

The system is just like the Church…It’s got a pope, the chairman; and a college of cardinals, the governors and bank presidents; and a curia, the senior staff. The equivalent of the laity is the commercial banks. If you’re a naughty parishioner in the Catholic church you come to confession. In this system, you come to the discount window for a loan.

But unlike the Church, where the doctrine of Papal infallibility remains on the books since it was first put there in 1870, the Fed under Yellen thankfully remains fully aware that it could make a mistake and set back a US economy that continues to make tentative progress in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

And there’s good reason to fear a policy screw-up. In slow recoveries that come after well-known financial crises—such as the US in the 1930s or Japan in the early 1990s—central banks and governments have tended to err on the side of tightening policy too fast. That’s what Japan did in 1997 when it raised taxes just ahead of Asian financial crisis, tipping the country back into deflation. And that was the case in the US in 1937, when the Roosevelt government—thinking the Depression was licked—tightened fiscal policy and the Fed raised interest rates slightly, a combination that became known as the “Mistake of 1937.”

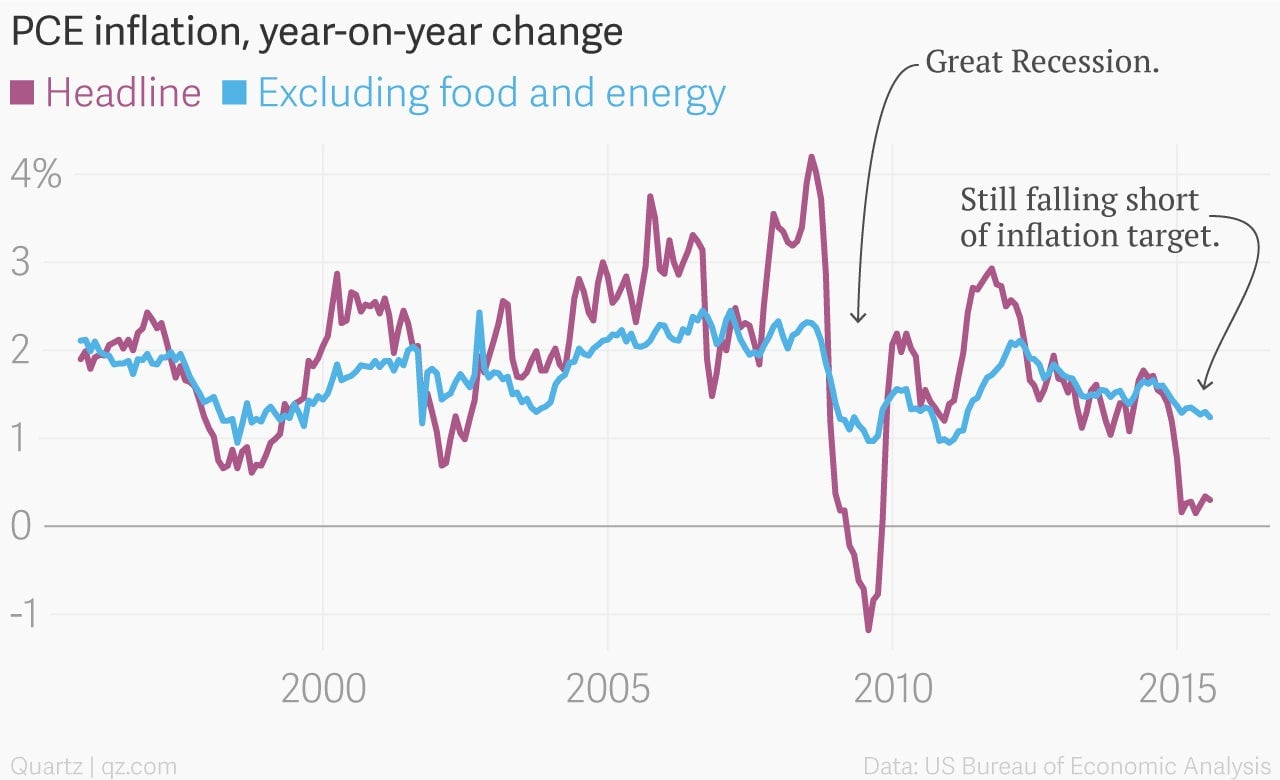

At any rate, in explaining the Fed’s decision earlier this month to hold off on raising interest rates, Yellen highlighted persistently low market measures of inflation expectations. That’s a sign that the markets doubt the central bank’s ability to actually generate enough inflation to get back to its 2% target. And for good reason, the Fed has consistently been undershooting its inflation target in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

Today the markets are registering even deeper doubts about the Fed’s ability to generate the inflation the central bank wants to see. Market measures of inflation expectations—known as breakevens—are hitting their lowest levels in more than half a decade. Today (Sept. 24), the five-year breakeven rate is roughly 1.11%, meaning that investors expect inflation to average roughly 1.11% over the next five years, far below the Fed’s 2% target.

The Fed’s persistent undershooting of inflation doesn’t mean the US economy is going to stall out. By most accounts, job growth continues to be strong. But it does complicate Yellen’s ability to begin to move interest rates higher. That makes her upcoming speech a curiosity for anyone who wants to see if she will downplay the low inflation expectations embedded in the market, and signal that she expects interest rates to rise sometime before the end of the year.

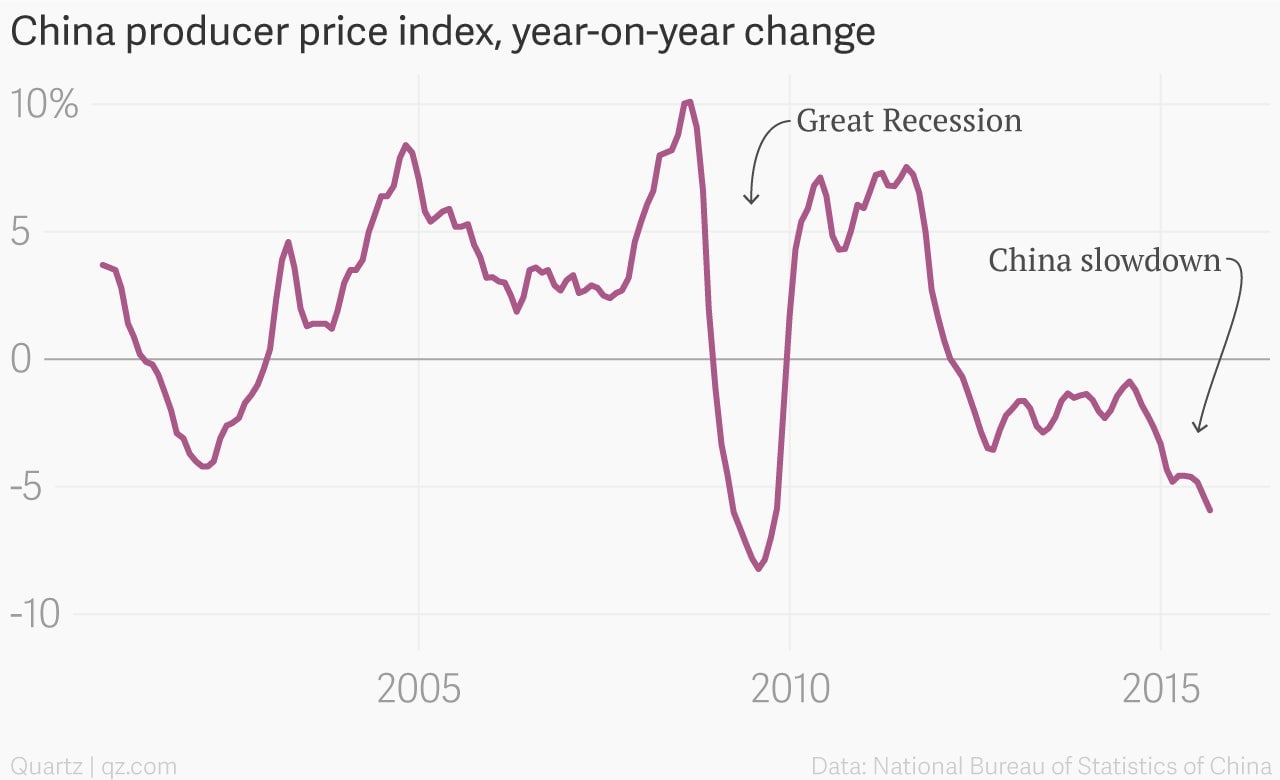

Of course, a lot of the deflationary pressure the US is experiencing is out of the Fed’s hands. For instance, China’s industrial sector—where soft demand is hammering prices lower—has become a significant exporter of deflation to the US and the rest of the world.

That’s one of the reasons the Fed will need some sort of a miracle to raise rates this year.