In the heart of Berlin, a beloved kink shop is a charming, healing presence

From outside, the Butcherei Lindinger looked like any of the other kink shops in Schöneberg, Berlin’s historic gay district.

From outside, the Butcherei Lindinger looked like any of the other kink shops in Schöneberg, Berlin’s historic gay district.

One mannequin in the window was accessorized with a ball gag; another wore what appeared to be a leather diving mask of sorts, connected to a metal leash. Inside, the store was brightly lit, its walls lined with leather jackets, vests, pants, and harnesses. Shiny steel sex toys shone on a shelf. A glass case held items I couldn’t quite identify, but which looked medical in nature. (A urine bag was apparent thanks to its label.) Collars of various colors hung from butcher’s hooks behind the checkout counter—actually a hip-high, vintage metal operating table—framed with stacks of lube carrying labels such as Slam Dunk, Elbow Grease, and old-fashioned Crisco.

I had spent the previous few days covering Berlin Fashion Week, and had seen some impressive shows, to be sure. But none, I would later discover, would channel the power of fashion quite like the Butcherei Lindinger. What I didn’t realize, as I wandered under the store’s red striped awning, was that it was far more than just a selection of kinky clothes and sex toys. It was a special kind of haute-couture hotbed: a fantasy factory where artisans and technicians craft peoples’ deepest desires into clothing.

Hardcore as it may have appeared, the Butcherei’s business is closer to the original notion of couture than that of any of the designers whose creations I’d seen that week on the runways. And Berlin’s tragic and beautiful history of fashion, sex, repression, and liberation is as essential to the business as London’s old-school suiting is to the tailors of Savile Row.

I lowered myself onto a leather couch just inside the door with Marc Lindinger, the Butcherei’s founder and designer, and his business partner, Oliver Eiermann. With a strong jaw, narrow hazel eyes, and a thick silver ring through his septum, Lindinger resembled a human version of his store’s bull logo, which was emblazoned in red across Eiermann’s white t-shirt.

Glancing up, I saw a photo that depicted three men—Lindinger among them, I would later realize—nearly life-sized, engaged in a sort of train inserting objects between one another’s buttocks in what appeared to be an operating room.

My questions for the designer momentarily dissolved. Lindinger, tall and fit at 41 years old, smiled.

“I can tell you how it started,” he offered.

The power of fetish fashion

Before the industrial revolution made off-the-shelf clothing de rigueur, those who could afford new clothes typically visited a tailor and had them made to measure. Today, bespoke suiting and couture dresses are reserved for the wealthiest or most notable of clients. The average fashion designer works to a punishing schedule, creating at least four collections per year, only to be knocked off by fast-fashion imitators.

By contrast, Lindinger works on a calendar dictated by his own creativity and the needs of his customers. The majority of his creations are not the ready-to-wear chaps, vests, and jackets I saw hanging in the shop, but custom designs created in a cellar atelier with painstaking attention to the highly detailed wishes of his clients.

Some of those wishes are relatively mundane: leather pants made-to-measure, or in a certain combination of colors. Others—such as animal masks, restraints and harnesses, and clothes with strategically placed zippers, flaps, and straps—are pure fantasy, and frequently sexual.

The power of fashion lies in the stories an item of clothing can tell—whether it’s a lucky pair of shorts a drummer wears onstage, or sharp stilettos that give a female CEO command in a boardroom. At its best, fashion can channel history, emotion, and narrative, and communicate it to others. I firmly believe in this power.

For the fetishist, however, that power goes far deeper. At the very least, fetish allows its wearers to tell stories they could never tell in a conventional setting: I am dominant; I am wild; I am someone—or something—entirely other than myself. At the far end of the spectrum, the fetishist’s attraction to an item or material can result in an appreciation that is, quite literally, orgasmic.

You might call Marc Lindinger a couturier of kink, but he is a couturier nonetheless. And a direct connection to his customers, the stories they want to tell, and their most intimate desires gives Lindinger a power most fashion designers can only dream of.

The busiest weekends at Butcherei Lindinger are those when the Folsom and Christopher Street fairs, the two epicenters of the leather fetish scene in the US, bring events to the German capital. What many of those leather devotees may not know is that the movement for gay rights and sexual liberation—like their wristbands, motorcycle jackets, and harnesses—began right there in Berlin.

Made in Berlin

In 1897—half a century before the American sexologist Alfred Kinsey challenged the popular understanding of same-sex desire as a disease or disorder—Magnus Hirschfeld, a Berlin-based doctor and scientist, founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee. Often heralded as the world’s first gay-rights organization, the Committee served as a research and community center in Berlin’s picturesque Tiergarten.

“Through science to justice” was the Committee’s motto, and Hirschfeld, like Kinsey, fought to prove that human sexuality was far more complex and fluid than society’s binary labels allowed. A century before countries started permitting same-sex marriage, he argued that “love is as varied as people are” and that sexual preference was innate, a natural, biological truth that shouldn’t be persecuted.

Berlin’s nightlife reflected similarly liberal views, as Robert Beachy documented in his book, Gay Berlin. In the late 1800s, the city was home to same-sex bars, dance halls, and costume balls. The police commissioner’s “Department of Homosexuals” kept an eye on things, but was tolerant. Gay culture flourished in the Weimar era, when Marlene Dietrich wore trousers, and the lack of censorship gave rise to nearly 30 gay publications by the 1920s. By the following decade, the city was home to nearly 100 gay bars, according to Beachy.

The scene attracted and inspired artists and writers from more repressed corners of Europe, including England’s W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood. The openness of sexuality in the city overwhelmed Isherwood—who would later pen the exquisite, pioneering 1964 novel, A Single Man—and he credited it with forcing him to face his own sexuality.

But the revelry—and its surrounding progress—was violently silenced once Hitler came to power. The Nazis destroyed Hirschfeld’s institute and library, raided and closed gay bars (though some were reopened to appease tourists during the 1936 Olympics), and issued orders that gay men be “hunted down mercilessly.” Between 1933 and 1945, the Nazis arrested around 100,000 men they suspected to be gay, and sent between 5,000 and 15,000 to concentration camps, where they marked them with pink triangles and subjected them to unspeakable horrors, including castration and murder.

In the years directly after World War II, the systematic destruction of Germany’s gay community and rights movement was little discussed. The number of people the Nazis killed for their sexuality during the Holocaust is still unknown—some estimate around 6,000—and it’s only recently that their loss has been acknowledged. The first accounts of gay Holocaust survivors were published in the 1970s, and a memorial for those who perished was only raised in Berlin in 2008. (At least one survivor lived to see it.)

Into leather

Nonetheless, there was an aesthetic connection between the Nazis and the gay culture they tried to destroy. The leather jackets worn by German aviators in World War I, and then by the Nazis in World War II, influenced one of the forefathers of the fetish scene: Touko Laaksonen, better known as Tom of Finland.

The Helsinki-based artist and adman drew gay men bulging with muscle and authority, a deliberate alternative to the effeminate stereotypes of the day. “The whole Nazi philosophy, the racism and all that, is hateful to me,” Laaksonen said. “But of course I drew them anyway—they had the sexiest uniforms!”

Laaksonen’s drawings of soldiers, bikers, and cops—among others—helped plant and spread the seeds for leathermen, as the subculture is still known today. (To this day, Eiermann said, about once a year Butcherei will receive a request for an item bearing a swastika, which they never produce, for both legal and ethical reasons.) In the ‘70s, artist and actor Peter Berlin perpetuated the image further with the 1973 pornographic film Nights in Black Leather, in which he played himself, a German immigrant, cruising the gay scene in San Francisco.

In 1980s New York, leather was the style for activists confronting the AIDS crisis head-on: “The military leather jackets, the big Doc Martens—there was a whole paramilitary thing going on,” said Mark Schoofs, then an AIDS reporter at The Village Voice. “It was because we were, in fact, fighting.”

Back in Schöneberg, Romy Haag’s drag disco, just around the corner from where Butcherei Lindinger sits today, helped the city’s sexually adventurous subculture flutter its eyelashes back to life. By the time the Berlin Wall came down, the gay rights movement—and the accompanying leatherman subculture—that arguably began in Berlin had spread worldwide.

Today, Berlin is one of the world’s greatest hedonistic playgrounds. The crown jewel of its nightclubs is the techno temple Berghain, which began in the 1990s as a fetish party. But on any given night in Schöneberg, and across the city, a smorgasbord of sexual theme parties take place, and dress codes abound, from latex to leather to nothing at all. The Wednesday that I met Lindinger, an alternative monthly listed a dozen such events taking place on that night alone. “Berlin is outstanding as a city of sex,” Lindinger said.

And it was the Berlin scene that brought him to the city from his home in Bavaria—where, as he said, “nothing exciting happens”—and made his business possible.

It’s personal

Like many of his clients, Lindinger himself has a fetish. He doesn’t just like leather; it turns him on.

“I always loved this natural feeling of the material, this heaviness, this sound of moving together, the leathers—and also the surface,” he said, gazing into the distance over my head as he spoke.

“It started as I was studying… I think it started there because my master”—he made air quotes as he said this, clarifying this was a master tailor, not the dominant member of an S&M relationship—“he had always leather in his cellar.”

At the time, Lindinger was in Nuremberg, studying traditional tailoring for men’s suits. But leather held a special attraction. The procedures were distinct; the machines were different; and because the material was costly and unforgiving—holes from an incorrect seam, for example, couldn’t be hidden—it presented special challenges for the beginner.

After working as a men’s costume designer, making bespoke suits for opera houses in Stuttgart and Zurich, Lindinger found his way to Berlin. In the beginning, he tended bar and worked in a fetish shop, which he declined to name. “I always had to sell rubbish,” he said.

When it came time to begin his own business, Lindinger knew his leather should be at the luxury level, and central to his brand. He first wanted to name it the Fleischerei, or “butcher”, but in Germany the word is reserved for actual butchers, so he settled for Butcherei—an homage to his material muse.

“Yes, it started there,” he said. “It makes a little firework always, if you touch the material.”

The couturier of kink

“Couture,” Tim Blanks wrote of Dolce & Gabbana’s fall 2015 alta moda collection, “gives [designers] an opportunity to slip the surly bonds of Earth and touch the face of God, a silken, gilded, embroidered, sequined, furry God who dwells in a realm of pure indulgent luxury, outside any of the prosaic restraints that bind designers to budgets and deadlines.”

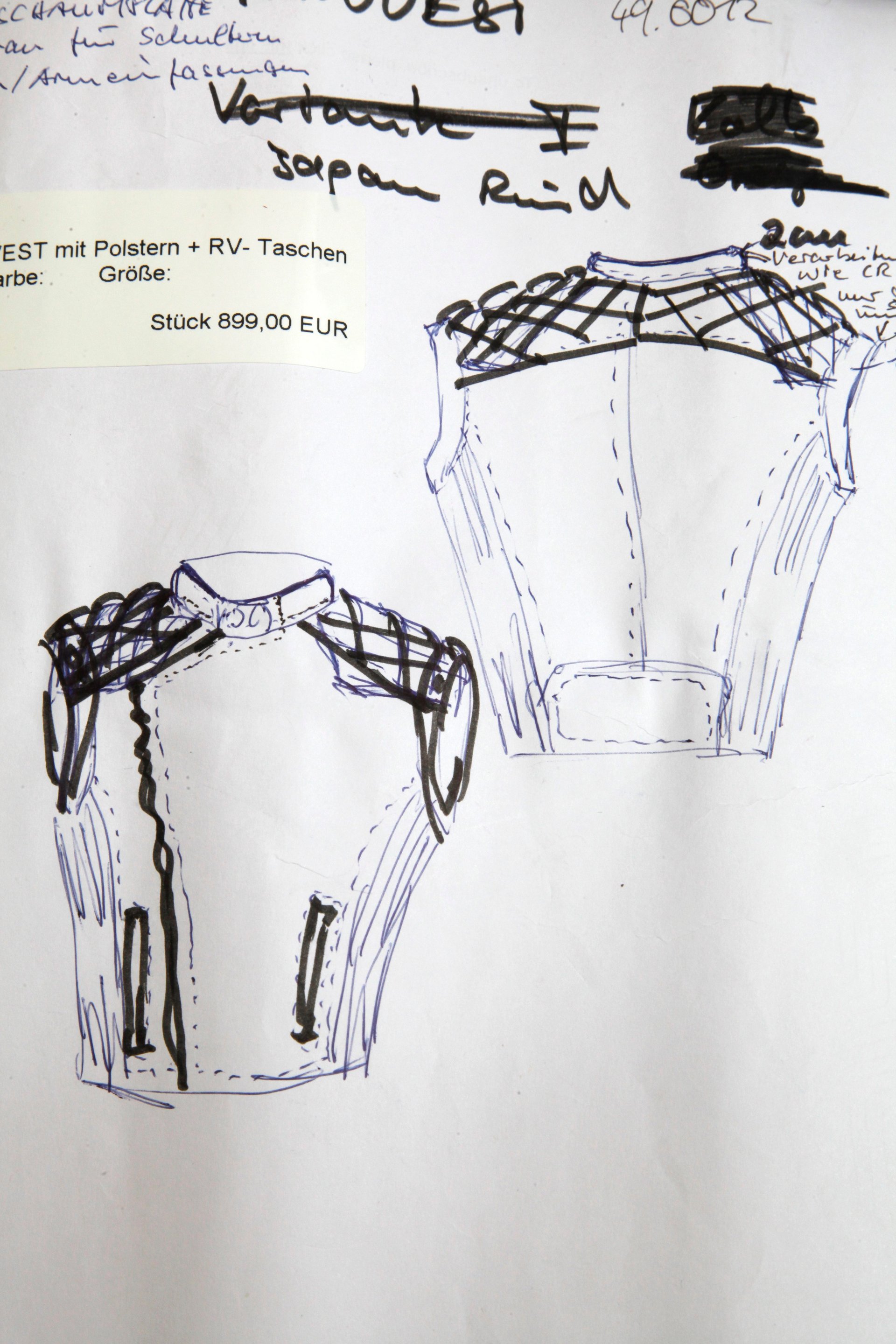

This is not unlike the realm Lindinger occupies. He still constructs custom garments the way he was trained with bespoke suiting—first cutting and sewing a model of the garment in cotton, and holding an initial fitting to verify measurements and details with the customer, before cutting the piece in leather or latex.

For the Butcherei’s ready-to-wear collection, he releases new styles as he sees fit and maintains his classics, such as quilted motorcycle jackets and leather pants that can be converted into chaps by pulling on the right zippers.

As you might guess, Lindinger is choosy about his materials. He sources leather only from European tanneries where processing treatments are verifiable. Because many of his creations are worn tight against the skin, and often in steamy situations, he won’t tolerate harsh chemicals or unsafe dyes. He favors cow and horse leather over sheep and lambskin, which tend to be weak, and finds his personal ne plus ultra in featherweight Japanese cow leather. “It feels light and soft, like if it’s your own skin over you,” he said. “It’s really fantastic.”

Lindinger pulled a pair of men’s pants in the buttery black material off a rack, where they hung with vests, shirts, and shorts of various colors. A fine, puckered ribbing covered the pants’ knees, butt, and crotch—codpiece style, with silver zippers on either side—to give the wearer ease of movement. Price tag: €1,849 ($2,104).

“In the industry, this is done by machine,” said Eiermann, pointing to the ribbing. “Here, the machine is called Krzysztof.”

Krzysztof is one of four employees in Lindinger’s downstairs atelier, along with an additional leather tailor (formerly of Jean-Paul Gaultier), a patternmaker, and a latex couturier.

Lindinger’s best customers are as particular as he is. The team had recently put the finishing touches on a pair of black custom-designed pants in heavy horse leather, which hung in wait for Peter Marino, the notable New York-based architect, art collector, and so-called “leather daddy of luxury.”

Marino, who designs stores for the likes of Louis Vuitton, Chanel, and Christian Dior, and homes for equally posh names such as Agnelli, Graff, and Rothschild, clearly could buy his leather gear anywhere. But at least a portion of it—three binders worth of personal orders, measurements, and specifications in Lindinger’s office—comes from the Butcherei. “They love me in Berlin,” he told Architectural Digest.

When a client such as Marino has a fitting at Butcherei Lindinger, at least three other people are present: Lindinger, one of the tailors, and Eiermann, who notes every detail specified, from the piping down the pant-leg to the bulge at the codpiece.

“Everybody just wants to play”

For someone like Marino, leather gear is part of a public persona. For others, its use is extremely private. Like any couturier, Butcherei Lindinger works with clients to fashion fabric into something to fit their fantasies, and their bodies. Some of those clients know exactly what they want; others require more consulting. In those cases, Eiermann helps counsel and coax.

“We are like priests or doctors,” said Eiermann. “People after a while, they tell us their secrets.”

In a small sewing room, Krzysztof sat measuring a pair of pants beside a machine, as daylight faded from the window. Next to his workstation, a long, coarse horsetail hung on the wall. The horsetail was real, and not unlike one Lindinger’s team had recently used to fashion a leather horse costume for a client—a custom job that included a full suit, harness, bit, jockey visor, and a detachable tail for about €4,000.

“There’s a special scene with pony play,” said Eiermann, remembering the female client who came in with her partner. “He decided how his horse would be dressed. That happens quite often, that a couple comes in and one of them decides what the other has to wear. You can see which has some dominant behavior.”

Other times, they receive requests via email: “Hi, I’m Bolt, a rubber pup,” read the beginning of one such note on a wall of works-in-progress. Another included a client’s sketch of a human face wearing a raccoon mask. The beginning of its embodiment, a cap with little peaked ears in supple grey leather, was tacked up beside it.

The deeper into Lindinger’s workspace I ventured, the less threatening—and more beautiful, in its way—it became. Many of the fantasies seemed impressively childlike. Had we been discussing a troupe of kindergarteners, “pony play,” doctor’s instruments, and raccoon masks wouldn’t have struck me as strange in the slightest. That case of what appeared to be medical supplies in the store, it occurred to me in retrospect, was just for grownups who like to play doctor.

“Often people come in, and they’re shy, because they think they are perverts,” said Eiermann. “But they’re not. So everybody just wants to play, and that’s what we try to assist.”

After all, sex can be an intensely personal, empowering expression of one’s identity—and all the histories, insecurities, and desires that come with it. But it can also just be fun. In this respect, it is much like fashion. And in his little shop in Schöneberg, Marc Lindinger has tapped into both—and managed to build a sophisticated, devoted, global clientele that would be the envy of any couturier.