What China will have to do to join the Trans-Pacific trade club

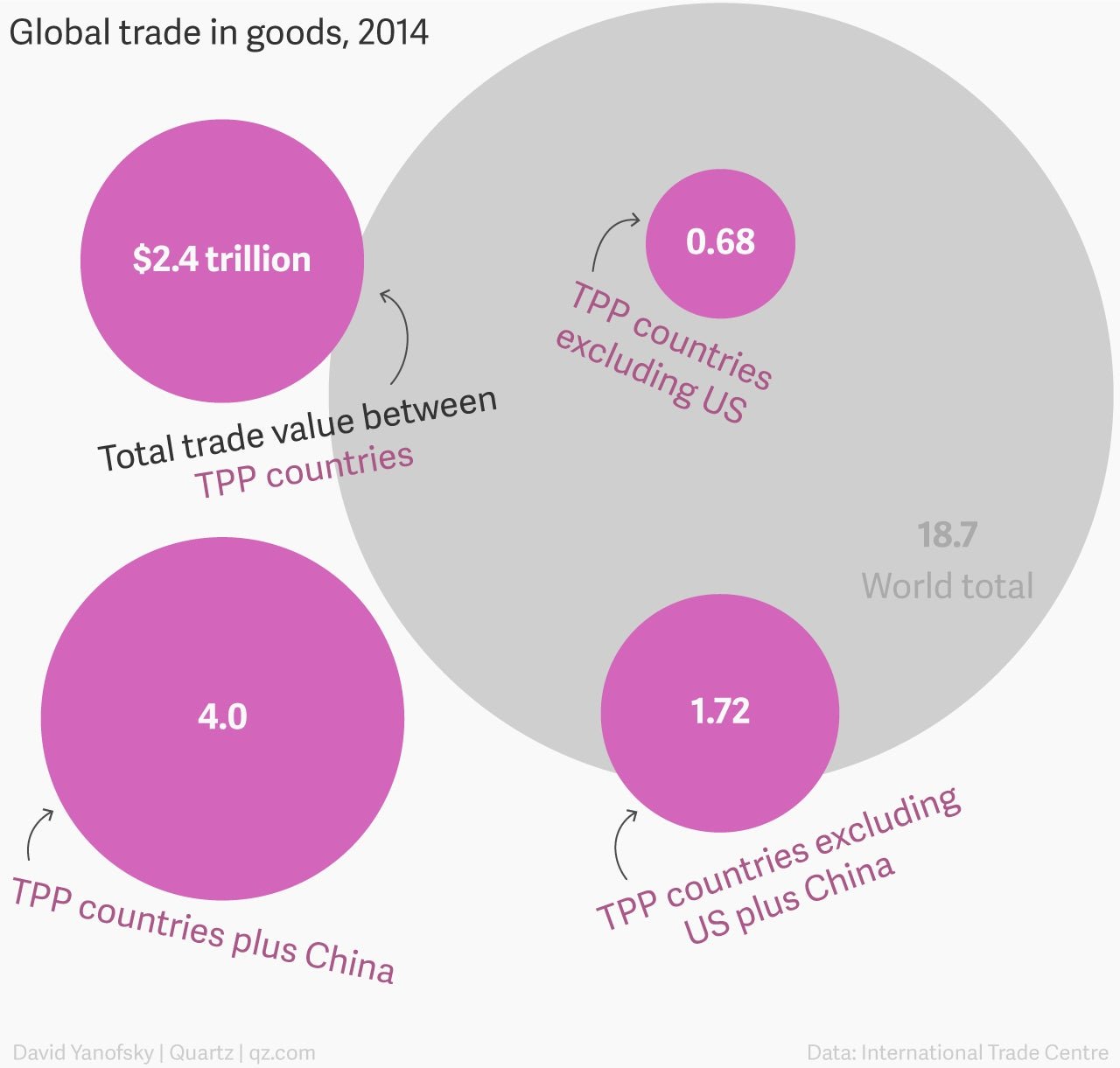

Twelve countries have reached agreement on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, arguably the world biggest-ever free trade deal. It marks a watershed pact that could open up trade between the United States, its allies, and many Asian countries. But one Asian country is conspicuously missing: China. That might not last.

Twelve countries have reached agreement on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, arguably the world biggest-ever free trade deal. It marks a watershed pact that could open up trade between the United States, its allies, and many Asian countries. But one Asian country is conspicuously missing: China. That might not last.

Barack Obama has at times framed the partnership, or TPP, as an effort to set free trade standards in Asia before China does. But China isn’t completely averse to signing on, as Obama has himself acknowledged.

Joining the TPP would require China to change old habits, even those it has kept after joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Because the TPP has been negotiated in secret, we don’t yet know specifics about the rules. The broad strokes of many of its parts are clear, however, and they suggest that China would have to undergo major changes to qualify. Here are the big ones:

Change tariff policies

One of the US’s stated objectives in proposing the TPP is to reduce tariffs on imports of agricultural products, textiles, electronic machinery, plastics and chemicals, and other types of goods. It cites a 40% tax on US chicken entering Malaysia as the sort of barrier to free trade it hopes to eliminate.

It’s true that China has steadily reduced tariffs on imports of some foreign goods, like diapers and skincare products. But it has also come under fire from the WTO for allegedly upholding import taxes when it shouldn’t be. Back in July, the WTO ruled China had violated an agreement to cease imposing tariffs on US steel products, which reportedly cost American steelmakers $200 million in losses. It also lost scuffles with the WTO regarding tariffs on US auto parts and rare earth minerals.

This mixed record suggests that China is likely to pick and choose the industries it’s willing to subject to international standards, and which ones it will keep under a protectionist umbrella.

Enforce intellectual property laws

While much of the TPP is aimed at reducing the role of the government—through lower tariffs, for example—the intellectual property requirements demand stronger enforcement.

IP theft is a common grievance among international firms that operate in China. In 2007, the US brought a dispute to the WTO accusing China of failing to live up to its IP protection promises. To America’s disappointment, the WTO ruled that China had not violated the relevant rules.

That appears to have led the Americans to bring more aggressive standards to the TPP, sometimes stoking controversy even among its allies in the deal. American negotiators, for example, pushed to give drug makers a 12-year period to withhold data that could be used to produce generic “biosimilars,” according to The New York Times. Other nations wanted five years of protection at most.

Even so, no amount of negotiation will bring the TPP’s IP rules to a standard low enough to include China, where piracy is widespread, enforcement is reluctant, and even the state itself is widely believed to play a role in hacking foreign firms.

“The crucial issue with China in IP is that the laws may be on paper but not implemented properly in practice,” according to June Park, a fellow at the National University of Singapore, writing in the online journal Asan Forum. “If China intends to join TPP, it will take years for implementation if the current levels of IP protection in China are applied,” she notes.

Get serious about the environment

Environmental protection is another core part of the TPP. A leak of the draft environment chapter from 2013 highlights the importance of curbing climate change by reducing carbon emissions. It also has several sections devoted to wildlife conservation.

China’s leaders have acknowledged pollution reduction as a high priority, both domestically and internationally. It recently pledged to the UN it would cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 60% per unit of GDP by 2020.

But it’s not clear if China has the might to win the war on pollution on its own shores, let alone commit to goals and standards set by outsiders. Despite pollution levels falling by an estimated 11% last year, China’s environmental ministry reported that 66 of China’s 74 major cities still fall below the acceptable national standards for air quality.

China has also struggled to prove its commitment to conservation. The TPP singles out overfishing as a key area for focus. While conclusive data remains unavailable, research suggests that China is responsible for much of the overfishing in Asia and Africa. As it prepared for an IPO, one fishery even wrote in its prospectus that didn’t fear international restrictions on overfishing because it knew the Chinese government wouldn’t enforce them.

China likely remains sincere about its commitment to improving the country’s environment, but only to the extent that public discontent threatens social stability. When it comes to the environment’s relationship to the economy, the latter tends to take precedence.

Actually liberalize its economy

The TPP also aims to open up services and investment between member nations. This means removing preferential treatment and protection for local service providers, tech firms, financial institutions, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

This in fact points in the very direction that China is already moving. Many of its recent bilateral free-trade agreements include provisions on services and investment liberalization. China last month laid out a plan to “improve the competence of SOEs and turn them into fully independent market entities.” It will even allow foreign investors to play a role in SOE reform.

Similar promises have been made for financial reforms. At a meeting with American and Chinese business leaders, president Xi Jinping said that his country aims to further remove barriers to foreign investment.

But moving in the right direction is not the same as reaching the destination. China may want to make SOEs more market-driven, but it will not scrap preferential treatment of them any time soon. And while fewer domestic sectors remain off-limits to foreign investment, the list is still very long. For China to join the trade agreement, it will take a sustained effort to level the playing field for TPP members operating in the country.