As state leaders and delegates descend on New Delhi this week for the third India-Africa Summit, Indian officials are working hard to differentiate their country from China, the African continent’s leading Asian partner.

“Our partnership is not focused on an exploitative or extraction point of view, but is one that focuses on Africa’s needs and India’s strengths,” said Vikas Swarup, a spokesman for the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, alluding to criticisms that China exploits the region’s resources. India’s minister of commerce and industry described Africa and India as “old friends and old family,” drawing a distinct line between China’s relatively recent entry into the continent and the 2.16 million members of the Indian diaspora that have been living in Africa for generations. Last week, prime minister Narendra Modi claimed that India has emerged as a major investor in Africa, “surpassing even China.”

It’s an attempt to catch up to China, one of the Africa’s largest trading partners, now that India needs more energy and commodities to fuel its industries, as well as diplomatic support for strategic moves like India’s bid for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. Another summit focusing on India-Africa economic ties will be held in Nairobi next month. Then in a little over a month, South Africa will host the 6th Forum on China-Africa cooperation.

But it’s not clear that India is that much of an alternative to China. The kind of relationship that Delhi is pitching—one focused on mutual need, helping Africa grow, and south-to-south cooperation among two formerly colonized, now fast-developing regions—sounds a lot like what Beijing has pushed for years.

Indian trade with the continent has so far been heavy on commodities, which goes against goals of developing Africa’s productive capacities and moving up the global value chain. About 84% of Indian imports from Africa last year were raw materials like crude oil, cotton, and precious stones for India’s diamond-cutting industry, the largest in the world. If Modi’s “Make in India” policy takes off, these imports will likely grow.

Indian businesses on the continent like to portray the competition with Chinese firms as one between private Indian businesses and entrepreneurs who employ African workers and spur the economy, versus large government-backed Chinese businesses who put little money in local sectors. But the World Bank estimates that private Chinese investment accounted for 55% of all Chinese direct investment in Africa by the end of 2011, with most of the spending in manufacturing and the service sector. As we’ve pointed out, the top 20 sectors for Chinese projects between 1989 and 2012 have been business, wholesale and retail, import and export, and transportation.

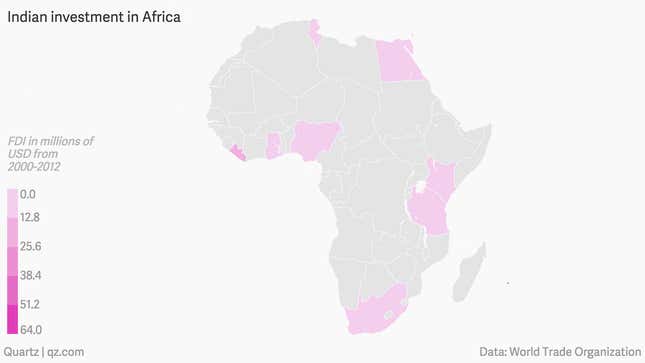

Modi is not wrong that Indian investment in Africa, estimated at over $50 billion, is more than that of Chinese companies, valued at $26 billion at the end of 2013. But over 90% of that goes to one country—Mauritius, once attractive for its textile industry, and now a popular tax haven. And Mauritius isn’t even on the continent (it’s a tiny island east of Madagascar).

Chinese policymakers, after years of clashes between Chinese companies and local workers, protests, and criticism from the African public, may be realizing that the continent needs more than trade deals, credit lines, and splashy infrastructure projects. Chinese officials have taken to hailing so-called “people to people” exchanges as the cornerstone of China-Africa ties, and this isn’t all lip service. In Kenya at least, large state-owned Chinese companies have started training programs for local workers as well as for students, to varying degrees of success. India might do well to learn from China’s experience, too.