Why Spain’s and Italy’s pain could be Germany’s gain

You might call it migration schadenfreude. As Europe’s economy falters, immigrants are streaming into Germany. And that’s happening just as Germany is confronting an acute shortage of labor.

You might call it migration schadenfreude. As Europe’s economy falters, immigrants are streaming into Germany. And that’s happening just as Germany is confronting an acute shortage of labor.

This tide of immigrants is a relatively new thing for the country. The difficulty of mastering German and the perception of administrative hurdles, among other factors, had kept the country’s immigration rate the lowest among Europe’s advanced economies.

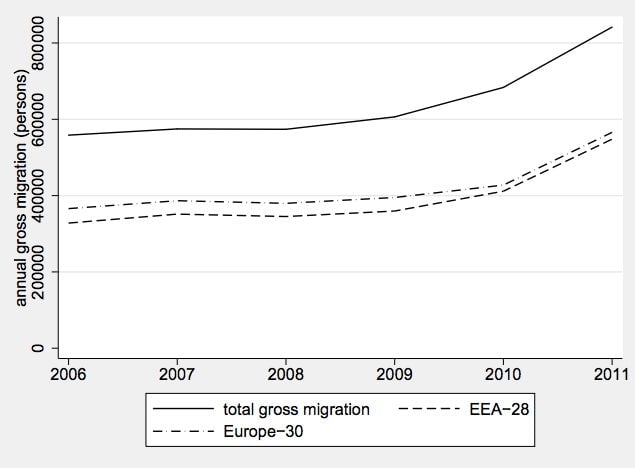

But after staying flat between 2006 and 2009, immigration to Germany jumped 40% in 2011 to total 840,000, increasing another 15% year-on-year in the first half of 2012, according to a paper (pdf) published last month by Spain’s Foundation for Applied Economic Studies.

Of course, Germany is Europe’s largest national economy and has fared much better than almost all of its European peers since the onset of the financial crisis. After shrinking 5% in 2009, the German economy has seen year-on-year growth since then (albeit just an estimated 0.7% in 2012). Its fellow euro area countries, meanwhile, have battled recessions.

But the spike in immigration to Germany is not simply due to people fleeing their ailing economies. Most of the double-digit increase observed by the authors of the report was from migrants in the European Economic Area (the 27 EU member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein). And, remarkably, 78% of that jump was the result of what migration researchers call the “diversion effect.” That is, about 200,000 workers chose to go to Germany instead of migrating to places like Italy, Spain or the United Kingdom. Here’s a look at that trend:

The authors, Simone Bertoli, Herbert Brücker, and Jesús Fernández-Huertas Moraga, explain how the diversion effect has played out in Germany:

Thus, during this period, immigration between a typical European country and Germany is explained to a much larger extent (twice as much) by changes in conditions in alternative destinations, typically Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom, than by changes in conditions in that particular country. For example, the surge in Romanian migration to Germany has much more to do with the Spanish economic situation than with the German or Romanian economic situation.

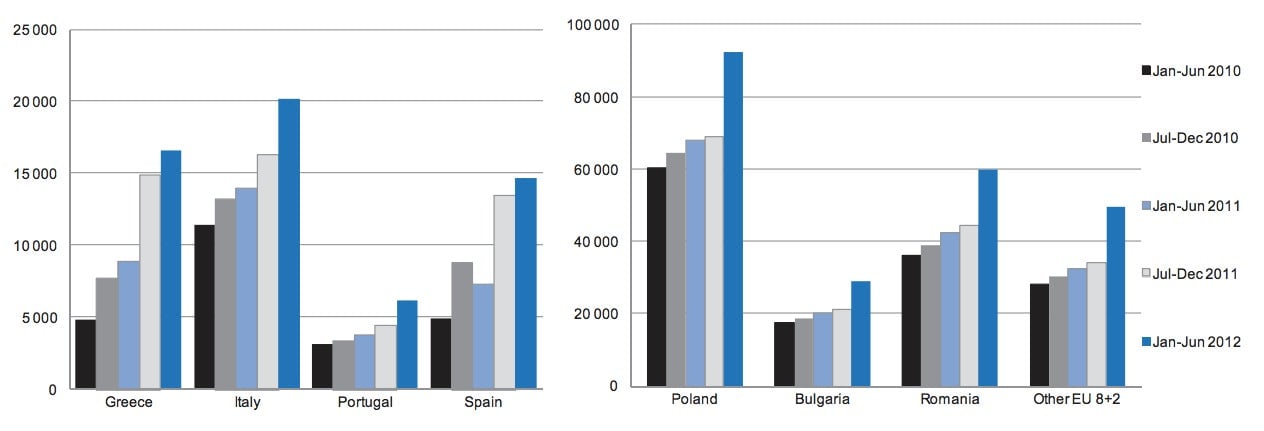

In other words, Germany didn’t get a bunch of Romanian workers simply because the economy was bad in Romania and better in Germany. Rather, migrants who would otherwise have headed to Italy or Spain opted for Germany instead, put off by the grim work opportunities in southern Europe. (Spain and Italy absorbed the highest number of migrants from Romania and Bulgaria before 2008, the authors note.)

Plus, for many of these migrants, the economy wasn’t all that bad at home. The majority of these laborers come from eastern Europe, which has generally suffered less than the economies of southern Europe. For example, even as Romania’s GDP per capita and unemployment levels stayed relatively stable, the researchers observed that Romanian migration to Germany increased five-fold between 2006 and 2012, at the same time that Romanian migration to Spain fell three-fold.

These eastern European countries have been exporting migrant labor to other European countries for a long time. As Bertoli et al. observed, more of them are now just heading to Germany.

That’s potentially a good thing for European labor markets. The fact that diversion accounted for so much of migration into Germany may signal that European labor is moving where it is needed. Or as Bertoli puts it, the labor market is responding to the “asymmetric shocks” in labor demand wrought by the financial crisis. “Migrants moving out of countries with weaker labor demand into countries with stronger demand can help the currency union absorb some of these shocks,” he told Quartz.

Put another way, Germany is helping to absorb the rest of Europe’s near-epidemic joblessness. This is important given the lack of labor mobility in Europe, compared with places like the United States. “The European economy really needs more professional mobility” (paywall), said Yves Leterme, Deputy Secretary General of the OECD, pointing to the benefit immigration has had on the US economy during the economic crisis.

Here’s the upside for Germany: Inflows of migration can help Germany repair a declining population. It now has one of the fastest-shrinking and fastest-aging among OECD countries, according to an OECD report released earlier this month. Germany’s population has been falling since 2004. And even with an uptick in population in 2011 from around 350,000 Eastern European immigrants, the country’s labor force is expected to decline over the next decade, as much as 4%, the OECD says.

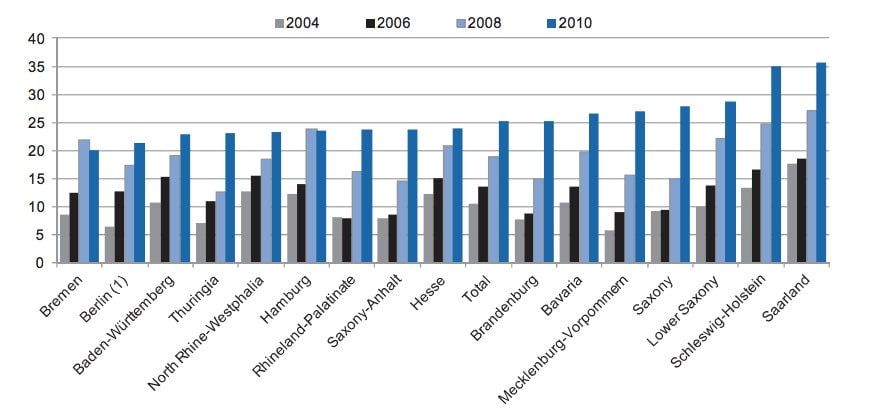

Moreover, according to the UN population forecasts, Germany will see about 60% more people leaving its working-age population than entering it in 2020, the worst rate of OECD countries, the report notes. Already, the number of German firms that said they were suffering shortages of junior staff has more than doubled between 2004 and 2010.

This coalescence of factors means that some 500,000 German jobs are currently unfilled. But these aren’t just any jobs. Germany is really hurting for skilled workers. (Scientists, electricians, plumbers and engineers, nurses, and IT staff are particularly thin on the ground.)

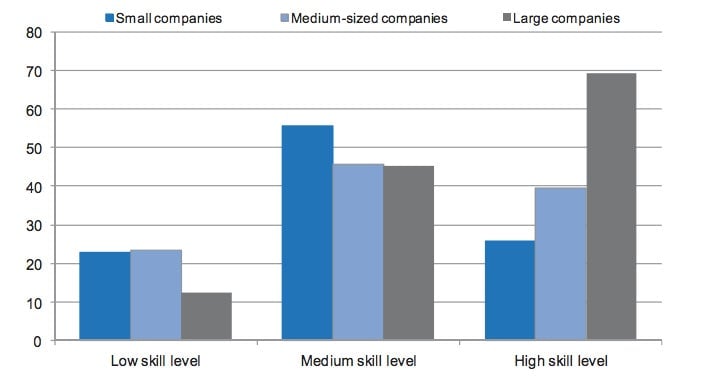

Already, the government, along with some businesses, has been recruiting workers in these fields from overseas. This campaign includes programs that pay for recruits to learn German in their home countries and things like the roll-out of this site. However, the vast majority of German businesses haven’t considered recruiting abroad, said the OECD.

Even if its current recruitment drives are targeting so-called medium-to-high-skilled workers, Germany does still need people who aren’t so specialized—low-skilled workers to fill jobs that require at most a secondary education (meaning, high school or vocational college). However, demand for those workers isn’t rising—and may even be falling. That’s even though roughly twice as many migrants entered Germany under the country’s skill and high-skilled categories compared with under low-skilled categories, the OECD report says.

But even though Germany might need more laborers, many among the country’s trade unions and residents are wary of the inflows of migrant workers. Officials this week called on Romania and Bulgaria to better integrate their Roma ethnic minority, in hopes that this would help lessen the flow of Romanian and Bulgarian migrants to Germany, believed to be in part made up of Roma. Earlier this month, the German Association of Cities recently blamed rising organized crime on migration from Romania and Bulgaria. It then called on Prime Minister Angela Merkel to help cities like Berlin, Hanover, and Hamburg handle what they said was a six-fold increase in migration to their cities. Natives are particularly worried that the 2014 lifting of a seven-year stay on the free movement of Bulgarian and Romanians in the EU will prompt an even bigger flood of migrant workers.

They are quite probably right. Though Germany’s economy contracted in the last quarter of 2012, it’s already showing signs of a return to growth this year. That means that regardless of which types of workers Germany hopes to recruit—skilled or unskilled, migrant or bona fide immigrant—as the rest of the euro zone slides deeper into economic contraction, Germany stands a good chance of attracting more of all of them.