Meet everyone’s new favorite currency: the Mexican peso

Big jumps in foreign investment presaged rather nasty episodes in Mexico’s financial history back in 1982 and 1994. The “tequila crisis“ that culminated in the violent devaluation of Mexico’s currency in December 1994 left the country in financial ruin from which it has still, some argue, not fully recovered. So it might seem strange, indeed a little worrying, to see the build-up of enthusiasm around the peso lately. Wall Street currency and bond trading desks are vigorously peddling a range of ways for clients to play peso, or MXN, as it’s known in the markets.

Big jumps in foreign investment presaged rather nasty episodes in Mexico’s financial history back in 1982 and 1994. The “tequila crisis“ that culminated in the violent devaluation of Mexico’s currency in December 1994 left the country in financial ruin from which it has still, some argue, not fully recovered. So it might seem strange, indeed a little worrying, to see the build-up of enthusiasm around the peso lately. Wall Street currency and bond trading desks are vigorously peddling a range of ways for clients to play peso, or MXN, as it’s known in the markets.

“We would recommend that investors build long MXN positions to benefit from the risk-on environment. In addition to our short [Brazilian real vs. peso] and long [peso vs. Chilean peso], we have added a short [US dollar vs. peso],” wrote BNP Paribas analysts earlier this week.

“With risk assets poised to move higher in the near term, we favor MXN among [emerging market currencies],” wrote Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts.

“Currencies such as the MXN should benefit from this risk rally. What’s more, MXN is one of the few currencies in LatAm not at risk of strong-side intervention,” wrote Morgan Stanley analysts.

Like other Latin American nations such as Brazil, Mexico is likely to face an incoming flood of capital over the next few months, as central bankers around the world crank up the electronic printing presses to create fresh cash to pump into their respective economies—the famous “quantitative easing”. That inflow of foreign investment into countries like Mexico puts upward pressure on their currencies, a potential drag on growth for these export-dependent nations. (In general, weak currencies are good for exporters, as it makes their products cheaper for foreigners.)

In the past, Brazil has led a counterattack against waves of foreign capital generated by quantitative easing in countries such as the US. In the financial equivalent of heaping sandbags atop a flood barrier, the Brazilians launched a series of capital controls in recent years to try to stem the inflows. And officials there are threatening to do more, which is already making some investors think twice about placing bets that the Brazilian real will grow stronger.

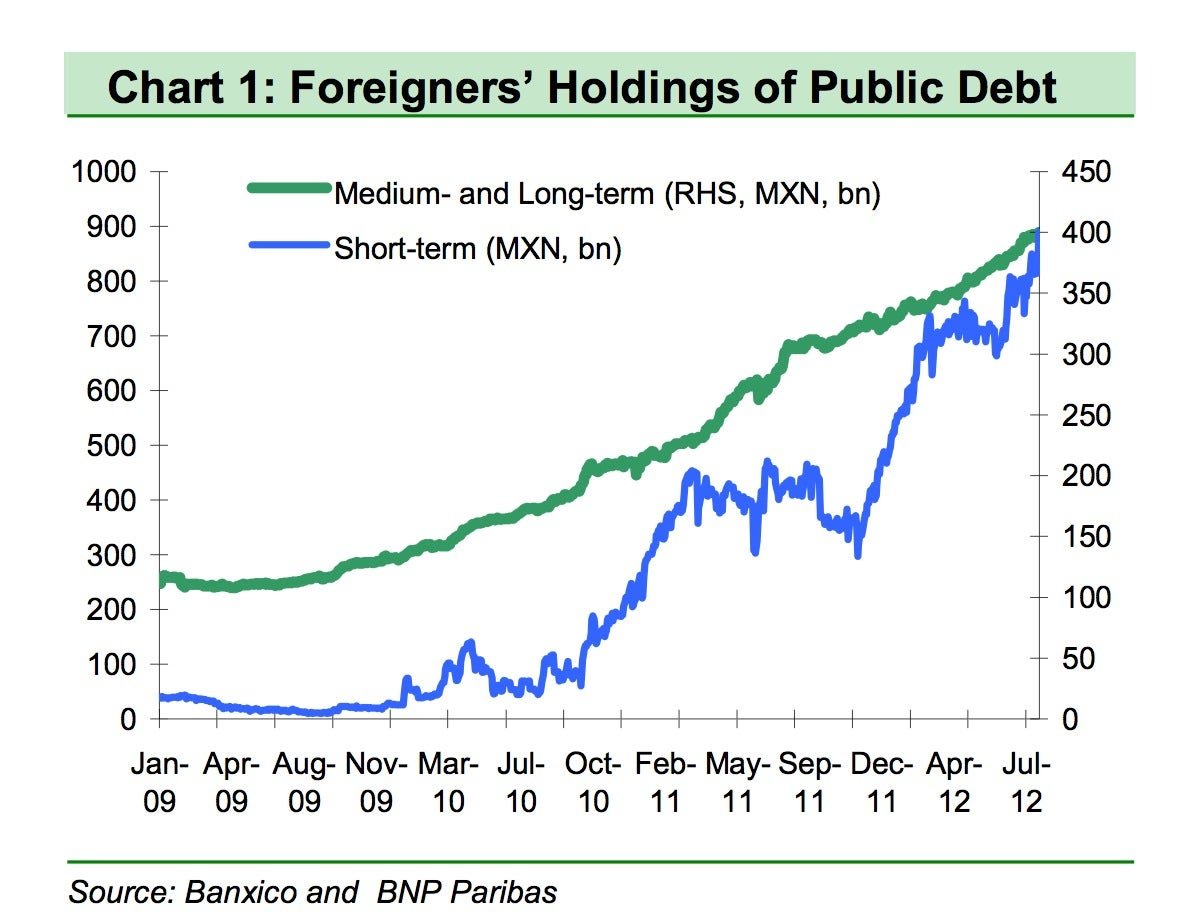

Mexico seems a far better wager for them. And the inflows tell the tale. External debt—in both pesos and foreign currencies—totaled 36% of central government debt in 2011, up from 24% in 2009, according to Standard & Poor’s. And foreign interest in Mexican government debt seems to be picking up more steam, according to this chart from BNP.

Why Mexico? For one thing, policy-makers there have shown little sign of being interested in the types of interventions used by Brazil. For another, appreciation in the peso would likely be seen as something of a welcome development there, as Mexico continues to grapple with unwelcome—though far from catastrophic—inflationary pressures. (All else being equal, a strengthening currency tends to counter inflation.) And for what it’s worth, the peso still isn’t exactly steroidal. Versus the US dollar, the peso is still some 20% weaker than its August 2008 level, according to BNP Paribas analysts.

Finally, in other respects 2012 is not 1982 or 1994. Prices for oil—the source of roughly 35% of Mexican government revenues, according to Standard &Poor’s—show no signs of impending collapse. It was diving petroleum prices that set off the 1982 panic, as investor doubts about the government’s ability to service its debts ultimately triggered a panicky flight of capital. And in 1994 an unsustainable currency peg to the US dollar, combined with a big fiscal deficit and an armed uprising in the south, set the stage for a chaotic currency crisis. Recent governments have been more fiscally prudent, though the current spasm of narco-violence doesn’t exactly scream stability.

Still, let’s hope investor enthusiasm for Mexico doesn’t get too exuberant. The country is right now in its long, uneasy post-election handover period; and after a 12-year absence, the PRI, the party whose 71-year-rule encompassed the last two crises, is coming back into power. In other words, easy on the tequila, everybody.