Facebook just became a $300 billion company. Here’s what that means

Stock in Mark Zuckerberg’s social media behemoth is on a month-long surge. Facebook shares are up nearly 41% so far in 2015 and roughly 8% over the last week after its latest earnings report blew away expectations after the close yesterday.

Stock in Mark Zuckerberg’s social media behemoth is on a month-long surge. Facebook shares are up nearly 41% so far in 2015 and roughly 8% over the last week after its latest earnings report blew away expectations after the close yesterday.

That rise pushed the value of the company—as measured by market capitalization—above $300 billion Thursday (Nov. 5), placing Facebook firmly in the ranks of the mostly highly valued companies in the world.

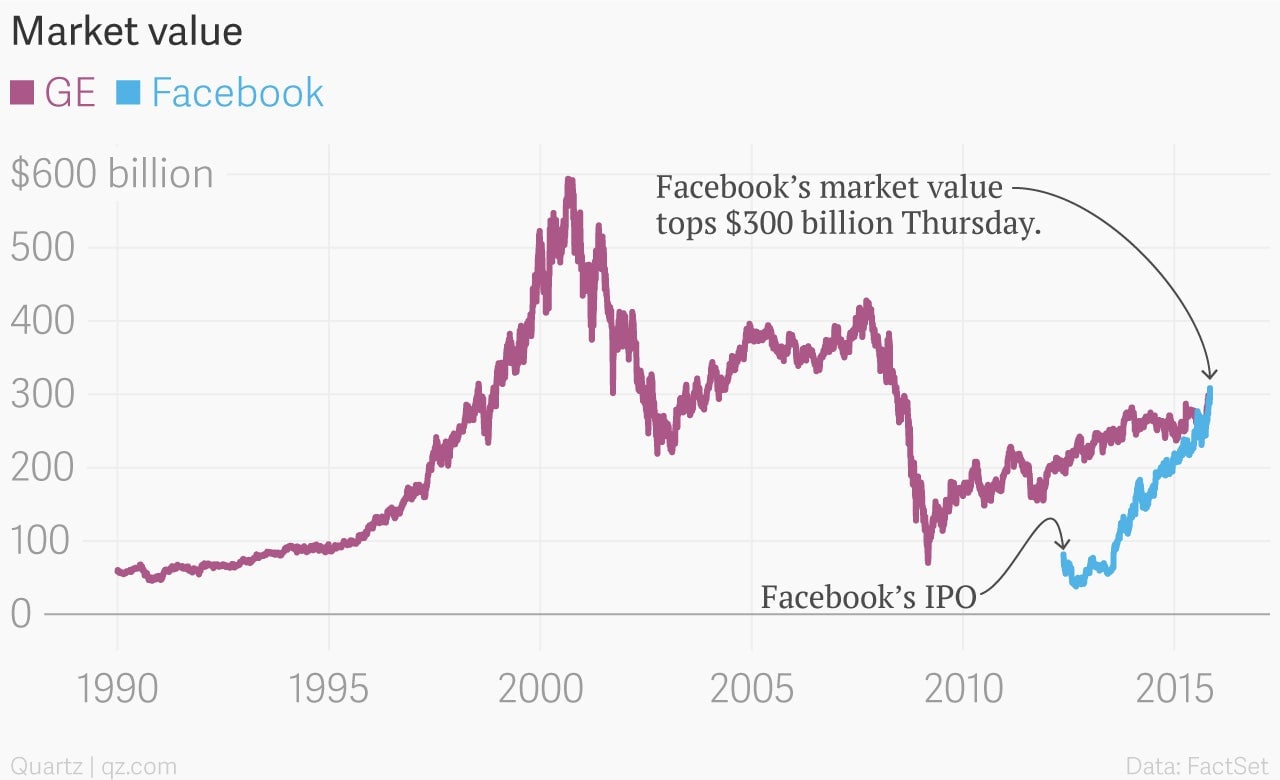

But the rising value of tech companies underscores a broader shift in the US economic landscape, as tech firms assume the dominant position once held by industrials. Case in point: Facebook’s value this year has soared above that of GE, which traces its roots back to Thomas Edison, the first wizard of Menlo Park.

The largest companies, by market value, in the S&P 500—Apple (~$680 billion), Alphabet/Google (~$520 billion) and Microsoft (~$435 billion)—are also all tech entities.

Of course, these are simply paper values. The market can quickly and drastically change its mind about the value of a company as its business prospects change. Just think back to the tech boom and bust of the late 1990s.

But the dominant tech companies of today are very different than the dotbombs of that era. For one thing, they are generating large and growing piles of profits and cash. What’s more, these companies centered around Silicon Valley are starting to warm up to the notion of dealing with investors. Since the arrival of Alphabet’s CFO—former Wall Street denizen Ruth Porat—the company has unveiled investor-pleasing initiatives, such as stock buybacks, that have helped supercharge the stock. Google parent Alphabet is up nearly 40% this year, handily outpacing the overall market, which is pretty much flat. And last year, for example, Apple was the second largest dividend payer in the S&P 500, returning more than $11 billion to shareholders.

The largest companies in the world today are a far cry from the industrial firms like railroads and steel mills that once dominated stock market capitalization. They have very little in the way of physical assets, and therefore they don’t require a ton of investment and they have very little need to borrow. (Sure, Apple’s borrowing money lately, but that’s only as a form of tax arbitrage and financial engineering.)

The fact is that the world’s largest companies don’t consume capital, today they throw it off in the form of stock market wealth and cash returned to shareholders. That’s a far cry from the world where companies like Exxon and General Electric were not only dividend payers, but made huge investments in the real economy as well.