Does “corporate culture” even exist?

The most important components of a company’s culture are its invisible, ineffable dicta. As we will see in today’s examples, they can lead competent, well-resourced companies astray.

The most important components of a company’s culture are its invisible, ineffable dicta. As we will see in today’s examples, they can lead competent, well-resourced companies astray.

In last week’s Monday Note I proposed that it’s not a technological misfit but a cultural chasm that separates Apple from the high-reliability “hard real-time” software that’s required for automotive applications. The post received a share of questioning commentary, both on the site and in private emails: Is a company’s culture really a limiting factor? Is it unmoved by the spirited words—and influx of industry veterans—that exhort and compel change? Does “corporate culture” even exist?

Today, I’ll follow up with a few examples that I have observed at close range over almost half a century in the tech world.

But first, let’s define our terms.

Culture is a set of tacit—and tacitly accepted—permissions to think, say, and do. In California-speak, culture provides license to emote.

For example, I’m born in [name a center of strong religious practice]. I go to the religious school; I learn the sacred texts and can recite them by heart; I “worship” daily—not as a task, but because that’s the way I’m wired. The rules and rituals are so ingrained I’m no longer aware of their workings. Like my family and friends, I live The Truth.

If religion doesn’t pull you, let’s use a different metaphor: Taste, as in taste buds. I’m born and raised in a land of corn flakes and orange juice, hamburgers and hot dogs. When I stop at a roadside restaurant while on vacation in France, I’m perplexed by the menu: tripe, boudin noir, lamb brains, ris de veau…Where’s the food? Under the surface of my awareness, my palate doesn’t recognize—it can’t even “see”—foreign flavors.

Company cultures are similar. We’re indoctrinated; we adhere to the rules, stated or not, that allow us and our ideas to be accepted (for if we don’t adhere…). The most powerful components of this culture sit below our conscious thought processes. These are the more dangerous ones: How can I change what I don’t see?

For example, we’ll start with IBM. In spite of its might, The Company, as it was once known, kept being overrun by one new product wave after another:

- In the 1970s, IBM and its mainframes lost the business computing market (temporarily, at least) to Digital Equipment Corporation with its faster, cheaper, general-purpose minicomputers.

- IBM ascended to the top of the PC industry, only to be dethroned by the horde of Windows+Office clones spawned by Microsoft, its erstwhile software supplier. IBM finally kicked its PC business to the curb in 2005, selling it to Lenovo.

- In 1994, when the internet finally emerged from academia, who “put the dot in dot.com”? Not IBM. Sun (as in Stanford University Network) Microsystems took center stage with its SPARC-based machines and Java programming language.

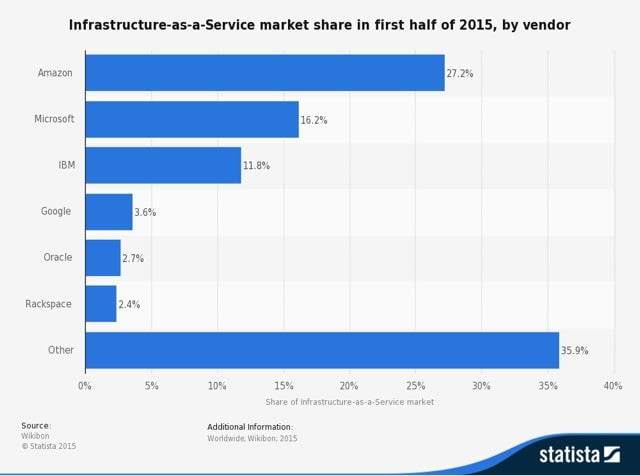

- As networks, storage servers, and software technologies aggregated into a new life form we call the Cloud, IBM had all the required building blocks… only to see Amazon jump ahead and grab a dominant share (27.2%), about as much as Microsoft (16.2%) and IBM (11.8%) combined:

There’s no need to mention smartphones in this list…

IBM survived these tribulations, of course, but just barely. The company is struggling (again), although, ironically, IBM’s DNA-level mainframe culture may be its salvation: The company is now attempting to ride into the 21st century by providing mainframe transactional processing in partnership with mobile device’s from Apple—the company IBM nearly killed thirty years ago.

Now let’s consider DEC.

The company missed the PC wave, and now is no more. At a dinner celebrating the Apple-DEC Strategic Alliance in 1988, I sat next to DEC CEO Ken Olsen. After swapping war stories (I once worked for Data General, one of DEC’s most important competitors), the grand old man confided, with charming honesty, that while he accepted that people bought lots of PCs, he just couldn’t understand why. At home he had a “glass teletype” monitor connected to a VAX back at the office that was running ALL-IN-1… What more could anyone want?

Ten years later, having never achieved any traction in the PC world and losing ground to Sun’s workstations and servers, DEC sold itself to Compaq, which sold itself to HP…

Sun Microsystems.

The company preached a gospel: The Network Is The Computer. Much like Ken Olsen, Sun execs thought PCs were temporary aberrations. What users want are cheap local devices, with just enough horsepower to display a sophisticated GUI, connected to a network of servers (Sun servers, of course). Meanwhile, they had Macs and LaserWriters in their offices so they could design and print acetate foils for their meetings.

Sun was upended by increasingly powerful Intel microprocessors and by millions of Unix-flavored servers built with parts from the PC clone organ bank. The company couldn’t foresee a world of 64-bit supercomputers in everyone’s purse or pocket.

Hewlett-Packard, my good old alma mater.

When I joined HP France 1968, the cultural split between the instrument people and the computer folks was clearly visible. It took HP more than thirty years to spin the measuring instruments business off as Agilent, which is now a stable, modest-size business (about one billion dollars per quarter).

On the computing side, the 9800 series once dominated the personal computers for technical applications segment. The company also came to own what we’d call mobile computing with its line of pocket calculators (see The Museum of HP Calculators), including several programmable models with rudimentary but serviceable magnetic storage. In retrospect, having 16-bit personal computers in the early seventies was quite a feat—one very much in HP’s tradition of technical excellence.

Then, in the mid-seventies, inexpensive eight bit microprocessors burst on the scene. Spurred on by magazines such as Byte, Creative Computing (edited near New Jersey’s Bell Labs, a veritable nest of computer geeks), and Dr. Dobb’s Journal of Tiny Basic Calisthenics and Orthodontia, hobbyists and their home-grown “microcomputers” (as they were first called) started the PC revolution, one that saw more than three decades of galloping growth.

HP looked down upon the Homebrew Computer Club “wizards” and their amateurish creations… and they lost the market. They came back briefly by riding Intel processors and Microsoft software, but life was hard in the clone world, and acquiring Compaq for market share didn’t make it any easier. Meg Whitman, HP’s latest CEO, eventually kicked out the PC and printers business but kept the Enterprise side—an entity with no identity and no differentiated culture or technology—to compete with the likes of IBM, SAP, Oracle, Dell, and parts of Microsoft.

And, again, we needn’t mention smartphones…

Last for this long list: Microsoft.

Microsoft saw the mobile revolution coming well before portable devices (or “PDAs”, back then) acquired cellular connectivity. In the mid-nineties, Microsoft created Windows CE as the operating system for “Palm-size PCs” (a name that greatly annoyed Palm, the company; the name was later changed to Pocket PC). Windows CE begat Windows Mobile and later Windows Phone, licensed, as usual, to Microsoft partners.

Things didn’t work out as Microsoft had planned, especially after the iPhone and Android came to the market. Microsoft concluded a grand licensing alliance with Nokia in 2011, essentially paying its licensee to use Windows Phone, only to be forced to acquire its failing partner in 2014. It wrote off the $7.6 billion acquisition price tag a year later.

Here, the cultural failure is obvious: Microsoft sees the world through a PC lens—it’s what made Bill Gates and his lieutenants billions. But as the Microsoft chairman wisely reminds us, “Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.”

Frank Shaw, Microsoft’s literate VP of corporate communications, is (actually, was—there is a new régime) an unashamed advocate of the PC-centric culture where mobile devices are “PC companions”—see “The IBM PC is 30 Years Old—And We’re (All) Just Getting Started“ and “Where the PC is headed: Plus is the New ‘Post’.” (Posted in 2011, these two pieces might also be hints that Microsoft foresaw the troubled future of its mobile business; this was about the time that Nokia fired its CEO and hired a Microsoft exec, Stephen Elop, to turn the company around.)

Today, Microsoft has no smartphone business to speak of, with less than 3% market share, a generous estimate that includes low-cost units not running Windows Phone software but Nokia’s legacy Asha.

None of these examples are the result of laziness or incompetence. The people involved sincerely thought they were doing the right thing—but they were betrayed by their culture. They got the right raw data about technology and markets but, unbeknownst to them, their emotional tastebuds pre-processed the information and passed a distorted picture to their consciousness, leading to bad decisions made in good faith.

A group of execs can easily be lured into thinking they have the money, people, technology, and time for an ambitious, transformative project, only to be subtly undercut by their culture—by an unstated, unseen reality distortion field.

As for the putative Apple Car: I hope this will be the mother of all counter-examples—that we will someday celebrate another of the company’s victories against received wisdom, this time a victory over the quasi-impossibility of changing a company’s culture.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.